Sydney Film Festival: one for the gleaners

Kirsten Krauth

The Werckmeister Harmonies

French filmmaker and theorist Agnes Varda is now in her 60s. In her lithe documentary, The Gleaners and I, she explores the often hidden worlds of people who salvage objects that others leave behind: a tonne of potatoes dumped because they’re misshapen, heart shaped, green vegetable leaves under crates at a Parisian market, grapes and apples left to rot, oysters left stranded after a storm. Varda gleans in her own way too, holding a camera rather than a sickle, sifting through digital images rather than metal by the roadside. Scrap crap. Shit bits. Fossicked through and spat out. She buys a clock with no hands and displays it proudly on the mantle. In France, gleaners have a certain nobility, are able to articulate their rights, protected by law. A chef in Burgundy roams the local hills looking for wild herbs. An artist makes “sentences from things.” People glean to survive, for art, by compulsion, or just for fun. Meanwhile, Agnes looks at her elderly hands, her thinning hair, trying to find the same empathy for her aging body that she shares with others she talks to: “I am an animal I don’t know.” Film festival goers become gleaners too, sifting through the rubble for those elusive odds and sods that can be shaped into lasting impressions. It’s harder than ever to get the full picture now that subscriptions only cover films at the State Theatre. It’s like watching the event with one eye covered. So here goes a “sheltered view.

Innocent bystanders

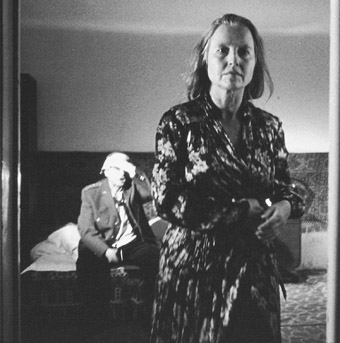

The Werckmeister Harmonies is the masterpiece of the festival, an overpowering look into the belly of the beast, or in this case the eye of a whale. What do you see? Good or evil? There’s the mysterious Prince who incites the members of a Hungarian village to rampage, riot and destroy. But does he exist or is he just a fiction created to justify others’ actions? A witness moves through this cold village. An innocent. He sees all, like the whale he loves to visit, stranded in a corrugated iron truck, tail piercing the village square, the night, like angel’s wings. In one of the most memorable beginnings in cinema, he pushes drunks at the bar into physical revolution, an embodied eclipse, where they play sparkling sun and moon and earth and twinkle twinkle little stars with their fingertips, spiralling and lurching around each other. He is a guardian angel unable to help, bleaker than Wenders’, watching and stepping with care. The monochrome and relentless cold and György Kovàcs’ exquisite music build a feeling of undefinable dread. It settles in your stomach, unnameable. It streams into the empty streets. Then the mob appears and starts to move, quiet except for footsteps. They ransack a hospital, destroying the equipment, beating the patients out of bed. No screams or cries of anguish, just a systematic, ruthless, unstoppable force, the fear heightened by the quiet.

Director Bela Tarr’s style is distinctive in contemporary cinema in that he rarely edits. The camera floats, smooth as a ghost, a dead man walking amongst hardened faces. Each scene is unforgettable: a policeman dances with his lover with a gun pointed triumphantly in the air. Loaded. His kids tear up and blow down the house, drumming with sticks, screaming “I’ll be hard on you, I’ll be hard on you”, each word a response to an inherited legacy of brutality, They control the world. Right now. While a dead whale lies in the village square, exposed, in streets that are burning.

How much profit is enough?

Bob Connolly, giving the Ian McPherson Memorial Lecture, says the best place to see documentary is in a “darkened hall surrounded by as many people as possible” and his methodology of narrative verité, being “prepared to film indefinitely”, results in high drama comic-tragedies/provocations like Rats in the Ranks and Facing the Music (which won most popular documentary at the festival). Anne Boyd is a good subject—frail, increasingly politicised, energetic, courageous, irritating, contradictory—and her love of music, along with the students’ exquisite soundtrack, infuses the film. It focuses on the gradual deterioration in teaching and resource standards of the Department of Music at the University of Sydney, due to the budget constraints meted out under university management and the federal government. The psychological damage on teachers aiming high within these environments is devastating. Staff start working unpaid. In the end, Boyd retires to concentrate on composing and second-in-charge Winsome Evans (“I can’t use the computer…I wouldn’t go to meetings”) has a heart attack. This is good drama but so much more. In a crucial scene, Boyd calls the Commonwealth Bank to try and muster some funding for a scholarship after spending hours composing on the computer—her ever-expanding duties as Head of Department now including sponsorship manager. It’s painful watching her negotiations, seeing her invest so much in her words, because you know that every charity is writing that same letter, every organisation coming up with its own buzz words, trying to entice the corporates to bite. This doco is a must see for every group on the fringes—artists, charities, academics, teachers, students—and anyone who believes, as Boyd quotes Beethoven, that “it is they who should give way to us.”

In August 1999, industrial giant BHP closed its doors in Newcastle. Steel City revisits the site, workers, management and community in the final stages. 2,500 workers are in a state of paralysis, having grown up expecting “a job for life” and feeling unskilled to tackle looking for work in a region as depressed as the Hunter. The documentary lovingly cares for these men and women, the men seen as vulnerable, described in feminine language—suckling on breasts—unable to defend themselves. Sometimes Kris McQuade’s voiceover verges on wartime-like propaganda, gearing into the sentimental—“this is where they lived”—as the camera traces the empty streets. Where the film is most successful is in the juxtaposition of management and workers. The marketing manager keen to get a media spin at all costs—he knows where his next pay cheque is coming from—staging a mock event of the last pouring of steel, inviting old timers to be involved: “it’s good business.” Front page news or bloated rhetoric? While Jack, who worked from age 14-51 at BHP, has no trade or qualifications but is learning to trust himself. And the others, who’ve never been for an interview, who don’t have “much literacy/numeracy skills”, get training from a service provider who says they need to “look outside the box.” The same workers who were told by BHP that “you’re not here to think, you’re here to do as you’re told.” The strangely moving image of a fiery process coming to an end.

Killing off the family

Made for the Hybrid Life series currently screening on SBS (see RT43 p14), The Last Pecheniuk is an unusual documentary in that it focuses on the negative aspects of being the child of immigrants in Australia. No soft-centred reminiscences packed up in a suitcase here. Instead, a tale of disaffection, a woman (the filmmaker Ness Alexandra), who changes her name to avoid the obligations of her Russian heritage, the pressures of being “the last Pecheniuk.” It’s a stylishly made film, Run Lola Run funky, complexly layered. Ness writes to an aunt who also ran away: “you were the big mystery…I imagined I was you.” The weight of expectation is heavy but there is love too. She sees her family as paranoid and isolated, her identity in Australia as trapped, bound and controlled as the Bonsai plants her grandmother so carefully tends.

Under the Sand is also about disappearance and reconstruction. Curiously resonant because of our cultural focus on the beach and the Harold Holt drowning saga, it’s about a middle-aged couple who visits a holiday house and head to the sand. While Marie (Charlotte Rampling in a memorable performance) is sleeping her husband enters the surf and when she wakes he is gone. That’s it. It’s disturbing because of its intangibility; there’s nothing for her or us to grab hold of. Is he just missing? Is he dead? Director Francois Ozon concentrates on Marie’s state of mind immediately after the disappearance and this is the film’s strange strength. It’s not quite grief. It’s not quite sanity either. She can’t miss him because he isn’t really gone. Yet. There are shifting surfaces, and sometimes it’s easier not to know the truth. When she finally relents and takes another lover, she laughs in the middle of making love and says, “you’re so light.” He’s not quite her husband. Rampling embodies in a very physical performance that sense of unreality when someone who touches you every day is no longer there.

Little boy dreams

David Stratton introduces The Apu Trilogy, Satyajit Ray’s classic black and white films tracing the life of a village boy, with a great story. When he was director of the Sydney Film Festival in 1968, he was approached by Ray to obtain a copy of Peter Sellers’ The Party for a private screening. Ray had just been offered a funding deal with Columbia, based on his script The Alien—an alien is befriended by a peasant—conditional on the agreement that Sellers played the part of the peasant. Stratton was forced to spend an excruciating few hours in Ray’s presence watching Sellers play an Indian After this, Ray withdrew from the deal.

The 3 films of the trilogy—Pather Panchali, Aparajito and The World of Apu—are quite different in tone and style. Pather is beautifully filmed and performed by a group of non-actors. Like Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (A One and A Two) the focus is on a small boy who sees everything but understands only pieces, oblivious to an adult world in which we become implicated. In Taiwan, a small boy takes photographs of the backs of people’s heads to help them see what they are missing. In India, Apu runs to his mother—he runs everywhere—with a letter from a long-gone father, evading his mother’s desperate hands. In Aparajito, it is the father who moves incessantly, in and out of the streets that wind down to the steps of the sacred Ganges, to be cleansed in water that is more diseased than he can know. Like Marie in Under the Sand, Apu becomes defined by absence, the deaths of sister, father, loved wife and an ambivalent relationship with his mother—which comes to haunt him in The World of Apu, when he takes on the role of absent father. Full circle.

There’s a woman who sits in the same seat every session at the State whom I dub ‘Voice of the People.’ After each film she announces loudly to the elderly women behind her a score out of 5. In Silent Partner, David Field and Syd Brisbane give headstrong, occasionally brutal, performances in a 2-hander that is about childish faith eternally unfulfilled. These men are close as family, prefer to buy cigarettes and alcohol than food, and completely naïve in their undertakings with the big boss. Based on a Daniel Keene play, the writing is understandably tough, unrelenting but sympathetic. Shot in 7 days on location at the greyhound races (where people just ignored the camera) and in various actors’ kitchens and bathrooms, it’s very low budget with a gorgeous sustained rhythm. The Voice of the People gives it 1 star out of 5. She says, “why would you bother making a film about 2 absolute losers” and then pauses, reflectively, “but Paul Byrnes seemed to like it.” I give the festival 2.5 stars—I have gleaned a bit but my bucket is half full.

Steel City, writer-director Catherine Marciniak; The Last Pecheniuk, writer-director Ness Alexandra, Dendy Awards, State Theatre, June 8; Facing the Music, writer/directors Bob Connolly, Robin Anderson, distributor Ronin Films, Australia; The Gleaners and I, writer-director Agnes Varda, France; A One and A Two, writer-director Edward Yang, Taiwan/Japan; Silent Partner, writer Daniel Keene, director Alkinos Tsilimidos, distributor Palace Films, Australia; Under the Sand, writer-director Francois Ozon, France; The Werckmeister Harmonies, director Bela Tarr, script based on book Melancholy of Resistance by Laszlo Krasznahorkai, Hungary/France/Germany; The Apu Trilogy, writer-director Satyajit Ray, India, Sydney Film Festival, June 8-22

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 20