Tempted south

Keith Gallasch previews the 1998 Melbourne Festival and overviews the ongoing arts festivals debate

Sabine Kupferberg, Gérard Lemaitre and Gary Chryst, Nederlands Dans Theater III

Notable for a festival launch outside of Adelaide, the artistic director seems happy to talk issues. While promising enjoyment and exhilaration, Sue Nattrass is also happy to talk “immigration, multiculturalism, the family, Indigenous arts, and equality” as “the topical issues that interest our community today and…are reflected in this year’s festival.” Not only that, but the 1998 Melbourne Festival has more character and sense of the contemporary in its programming than it’s had for many a year. Compared with Adelaide it’s still a restrained, rather modest looking affair with some parts of the program clearly superior to others, but it appears less determinedly middle-brow and more adventurous than its predecessors.

Nattrass says, she’s “wanted to produce a festival that could be experienced at more than one level” with “threads that link events together. One could, for example, look at Aboriginal culture through an organ and didgeridoo concert at Trinity College, 3 plays—one Stolen, a world premiere, a concert by Goanna, Aboriginal music and performers in the opening celebrations, an art installation at the Magistrate’s Court exhibitions, exhibitions at the Koori Heritage Trust and the National Gallery of Victoria, a symposium at the Victorian College of the Arts, and two photographic exhibitions—one of urban Aboriginals, and, in contrast, one of communities in central Australia.” She indicates you can also follow an Italian cultural strand, or pursue themes of (anti-) violence, or the family, or multiculturalism through the weave of the festival. For Melbourne, this connection with community and issues promises to offer the festival some of the distinctiveness that it has hitherto lacked in going for broad appeal.

Festivals and their ingredients were a hot topic at the recent Imagining the Market conference in Sydney. Robert Fitzpatrick, director of Los Angeles Olympic Arts Festival in 1988—one of the rare Olympics arts events outside opening and closing ceremonies to be highly regarded—hoed into middle-brow complacency about Cultural Olympiad programming: “Atlanta botched it, Barcelona did it only slightly better. This is an occasion for Australia’s arts mitzvah …Safe programming and a low profile will not achieve the desired effect.” He also derided “giving people what they wanted” as “a formula for boredom” and invoked art’s power to “astonish and delight.” In Fitzpatrick’s moral universe, the safe bet “reduces the producer/presenter to being a poll taker, a pimp for present values.” You can only hope that word got back to the directorate of the Cultural Olympiad in their Sydney bunker, but their resistance is probably already up as Barrie Kosky weighed in once again, at the same marketing conference, arguing for truly distinctive festivals and declaring the arts in the Olympics “a complete waste of time, money and venues.” He was vigorously applauded.

The Melbourne Festival is not the Cultural Olympiad, but with Leo Schofield’s elevation from one to the other (with the Sydney Festival thrown in), issues of time, money and venues have become irritatingly prevalent. Schofield’s smug promotion of financially responsible festival management as the artistic criterion for success (with middle-brow programs to match) has led to slanging matches about box-office success. In Adelaide this year the press was on red alert for early box office figures and announced likely success on the first day of the festival. The recent report of Archer’s success having erased the debt of the 1996 festival and achieving a $300,000 surplus must have been galling to pragmatist directors who detest festivals with ideas and which look upon them as “experimentation in a playpen.”

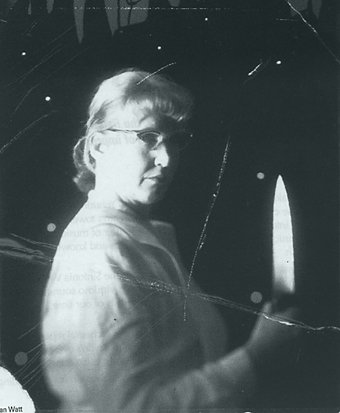

Christine Dougles, Love Burns

photo Julian Watt

Christine Dougles, Love Burns

Sue Nattrass has managed to maintain the traditional elements of the Melbourne Festival—the kind of things you’d expect to see any time of the year but with a bigger talent, eg not just any old soprano, but Sumi Jo, current queen of the coloraturas—but alongside more provocative material. The program includes a Bill Viola video installation, a strong line-up of international and Australian visual artists curated by Maudie Palmer in a challenging site, the Old Magistrates’ Court and City Watch House, Louis Nowra and Graeme Koehne’s detested and admired opera Love Burns (based on the same ‘true story’ that inspired the cult movie The Honeymoon Killers), hot UK choreographer Paul Selwyn Norton (see page 45) working with Chunky Move, the limit-stretching dance-physical theatre show Streb from the USA, from France Ballet Preljocaj’s Romeo and Juliet in a totalitarian state setting, Paul Capsis in the Kosky-directed “grunge” Burlesque, plus the festival’s continuing engagement with and reassessment of the works of Percy Grainger, this time on the electronic music connection.

As with the Brisbane Festival, the dance program of the Melbourne Festival stands out: Nederlands Dans Theater III, Ballet Preljocaj, Tango Pasión, Streb, and, from Melbourne, Chunky Move’s Fleshmeet and Company in Space’s A Trial by Video, an interactive dance work. Nederlands Dans Theater III comprises four older and incredibly experienced dancers in works by the company’s artistic director, Jiri Kylian, and should encourage choreographers and a generation of mature Australian dancers to work together. The dance program offers an interesting overview of contemporary dance from just how contemporary a ballet company can be in the form of Ballet Preljocaj (cf William Forsythe and Ballet Frankfurt’s great challenge to all other dance forms in the 1994 Adelaide Festival), to the riches of age, and the power of new media and popular culture.

The music program has its riches too, but in terms of scale and challenge is less scintillating—predictable servings of Beethoven et al with full orchestras while new music (and not so new) is relegated to smaller ensembles and concerts. The Chamber Music Sunset series is titled Music for the Millenium but its offering of Ravel, Shostakovich, Ives, Bartok, Janacek, Schoenberg and Debussy, while truly worthwhile (some rarely heard works) is more backward looking than millennial, save for the inclusion of Rhim and Schnittke, the only living (barely in Schnittke’s case) composers in the series. Electric-Eye places Percy Grainger in the history of electronic music, featuring Martin Wesley Smith and Ros Bandt discussing Grainger’s work, and with Bandt curating new Australian electroacoustic works and performances of Grainger’s Free Music for multiple theremins. Brisbane’s Elision are offering two concerts of contemporary works by Liza Lim, Franco Donatoni, Brian Ferneyhough, Mary Finsterer and others. Guitar Miniatures features Geoffrey Morris and Norio Sato playing an extensive list of works by, among others, Michael Atherton, Gerard Brophy, Chris Dench, Elena Kats Chernin, Raffaele Marcellino, Warren Burt and a selection of Japanese composers. The Rachmaninoff Vespers, a hit at the 1998 Adelaide Festival, is presented in Melbourne with, and this is unusual-to-odd, saxophone and percussion interludes.

In theatre, the Irish are coming, again, this time with the Abbey Theatre production of Thomas Kilroy’s The Secret Fall of Constance White, the story of Oscar Wilde’s wife, but, quite unexpectedly, performed in a blend of “Kabuki, Bunraku and European minimalism.” Gesher Theatre of Israel’s K’Far (Village) by Joshua Sobol was seen by RealTime at LIFT97 (London International Festival of Theatre). Although by no means Sobol at his best, this ambling, discursive play is well-served by a remarkable variation on the revolve-set and some astonishingly informal but precise ensemble playing that could only come out of a Russian theatre tradition. The translation experience is something else. Melbourne’s IRAA, another company working firmly within a European tradition, is presenting a new work Teatro, while Arena Theatre’s Panacea engages with steroids, youth and sport. Corcadorca Theatre Company’s production of Enda Walsh’s Disco Pigs, a winner at Edinburgh and Observer Play of the Year, is “a violent love story of dispossessed, disco-crazed seventeen year-olds”.

Former Kooemba Jdarra artistic director Wesley Enoch directs Stolen by Victorian writer Jane Harrison, a play about the Stolen Generation co-produced with Victoria’s Indigenous theatre group Ilbijerri. Deborah Cheetham in White Baptist Abba Fan and Leah Purcell in Box the Pony present Indigenous performances premiered at the Festival of the Dreaming that are steadily making their way around the festival circuit—Purcell in particular is not to be missed. Andreas Litras’ one-man show, Odyssey, in Greek and English, interplays Homer and the journey of a migrant woman to Australia. From Perth, Gerald Lepowski’s Dark is an account of the life of photographer Diane Arbus. Red, by Lucy Taylor, Rachel Spiers and Mark Shannon has emerged from the 1997 Melbourne Fringe, where it impressed Nattrass, into the festival mainstream with projections, live music and a lost memory with an obsession for…red. The cultural diversity of the theatre program, its commitment to the Indigenous, and to young audiences is clearer than anywhere else in the festival program. So too is its encouraging assemblage of diverse theatre and performance forms.

For the first time in several years I’ve been tempted by a Melbourne Festival—the last time was for the Glass-Wilson Einstein on the Beach, one of the great experiences, and then for Robert Ashley’s Don Leaves Linda with Chamber Made Opera. Melbourne doesn’t usually feature this kind of work, but there’s enough sense of adventure and inspiration across the board this time, enough sense of issues, ideas and forms, even if smaller in scale than deserved, as in the music program, to tempt me south.

Melbourne Festival, October 15 – November 1, http://www.melbournefestival.com.au

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 15