The aniconic and digital image

Heather Barton rethinks the spiritual and soft space in Malaysian New Media Arts at the First National Electronic Art Exhibition

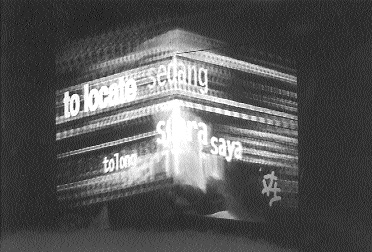

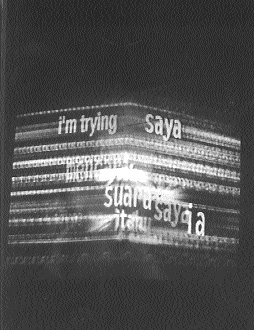

Hasnul Jaimal Saidon, I’m Trying to Locate, black & white video projection

photo Peter Spillane

Hasnul Jaimal Saidon, I’m Trying to Locate, black & white video projection

There is, it might be argued, a kind of ‘techno-orientalism’ surrounding new technologies when thinking the machine, soft-space and the digital-image in the western psyche: a pairing of high end technology with Asia in the western imaginary, if you will, however empirically inaccurate.

It gives rise to a ponderous situation where westerners operate with a technology and therefore a thinking which they do not ‘own’. When using new imaging technologies in the visual arts—if the modernist Greenbergian axiom around form and content and a Benjaminian assertion regarding the complex form of training imposed by modern technology can be indulged—what results is a kind of ‘blank canvas’ at the heart of thinking the digital image.

It was in this light that encountering the First National Electronic Art Exhibition at the Malaysian National Gallery in Kuala Lumpur raised particular considerations. If granted the license to think speculatively for a moment, one might wonder if the aniconic formulation of the image particularly in traditional Muslim art as it influences contemporary artists working with multi-media technology in Malaysia, does not somehow afford a greater propriety towards the digital image (if this is not to engage in a kind of [techno-]orientalism itself of another order).

The confounding of historical concepts of representation and analogy in western philosophies of the image are well documented in relation to the digital image (Binkley, T “The Digital Dilemma”, Leonardo, Supplemental Issue, Pergamon Press, Japan, 1997). What marks eastern philosophies of the image, particularly within the Islamic tradition, is the aniconic as opposed to iconic relation to the image that exists in the west. The aniconic are those images and symbols relating to deities that are non-figurative or non-representational.

Within Islam, Allah is inexpressible therefore non-representational. “No vision can grasp Him…” (Qur’an [Koran], 6:103). The spiritual order determines the aesthetic-formal order. Stylisation techniques exercised in calligraphy, illumination, geometric pattern and arabesque form the foundations for a tradition where the artwork in fact functions as a ‘cosmogram’. Not only does the aniconic concept of art in Islam make for an art practice arguably predisposed to a knowledge and use of the digital image—“knowledge and use” here in the Deleuzian sense of ‘savior’ which is an ability to make active, “a knowledge by description”, “a competence to produce” rather than reproduce (Deleuze, G. Negotiations, Columbia University Press, USA, 1995). But the ‘cosmogrammatic’ nature of the artwork when applied to the digital image overrides criticism often raised in relation to the electronic image in the west: that it is slick, glossy, dazzling, decorative, all surface and therefore superficial.

Surface ornamentation is the core of spiritualising enhancement, not a superficial addition in the Islamic concept of the artwork. This is not to add foreign elements to the shape of the object but to bring forth its potential, ennobling the object. “Through ornamentation the veil that hides its spiritual and divine qualities is lifted.” (Esa, S. Art and Spirituality, National Art Gallery, Malaysia, 1995) In Islam, beauty is a divine quality, God is beautiful and loves beauty. Beauty in art is that which generates the sense of God. Since beauty is a divine quality its expression has to be made without showing subjective individualistic inspiration. There is therefore no distinction between the material and spiritual planes. In creating beauty the artist is engaged in a form of spiritual alchemy and in doing so the soul of the artist undergoes a process of spiritual cleansing. This raises some very different notions around the artwork than those generated in the west around questions of abstraction, the sublime and the beautiful.

This is also not to say that the works exhibited during the First Electronic Art Exhibition in Kuala Lumpur were traditional in terms of technique or concepts. Far from it. The works that drew upon traditional methods or concepts did so with a rigorous critical distance and engagement. Nor were the traditional methods and form that were used and conceptual frameworks employed exclusively Muslim. Hindu, Taoist, animist and Christian traditions and metaphysics also come into play in Malaysian culture. But most contemporary artists in Malaysia have trained under a western art history syllabus with the majority, it seems, completing graduate degrees in the west. So there is certainly an engagement with western art history and art markets but often put to work in relation to eastern systems of ideas.

Mohd Nasir Bin Baharuddin’s four monitor video floor piece, for instance, works precisely in this manner. It encourages a deceptively pious response, although for a westerner one is even less sure why. The viewer is ceremoniously positioned by the work—submitting to its lure, sitting submissively at its feet, as it were, encircled by silent monitors across the soft opaque screen of which, runs a fluid arabic calligraphic script. The effect is mesmeric and contemplative. However as the artist, who is also the curator at Gallery Shah Alam, points out to a Muslim observer there would be questions as to why the monitors containing sacred script have been placed on the floor, indicating a lack of reverence. The script, however, is not from the Qur’an but Jawi, an arabic script spoken in Bahasa Malaysian (which is also written in a roman script) and which in fact many Malaysian Muslims do not even read themselves. And the text, far from being the word of god is everyday diary extracts. Baharuddin’s trick is a gentle one and works along side the temporal enquiries of the work, which are figured so that the piece never ‘begins’ as such. An allusion perhaps to the ‘awan larat’ (arabesque), a pattern so interconnected that it is impossible to trace the beginning of each motif. Within the installation the viewer is placed in one physical position but one which triggers many different and simultaneous readings of the position. The space in the midst of the monitors is also the space of the traditional cross-legged village story-teller, but the ‘audience’ of monitors tell story fragments that becomes the viewer’s, the ‘centre-piece’s’ own, confusing the places of teller, told and tale.

Hasnul Jaimal Saidon, I’m Trying to Locate, black & white video projection

photo Peter Spillane

Hasnul Jaimal Saidon, I’m Trying to Locate, black & white video projection

Hasnul Jaimal Saidon’s CD-ROM work, Ong (slang for “hot streak”), from his solo show Hyperview, was shown along with his I’m trying to Locate, a video-projected, corner piece that creates the optical illusion of a three dimensional space out of a flat wall. The black and white piece uses Chinese pictograms, English and Bahasa scripts over a textured electronic weave evoking traditional Songket. Textiles, historically have a sacred and ceremonial function as does calligraphic script which is said to be “the divinely written pre-eternal word which brings the faithful into immediate contact with the Divine Eternal Writer of fate and from there even profane writing has inherited a certain sanctity.” (Islamic Calligraphy, Leiden, 1970) This work and the others exhibited, while either overtly concerned, less so or not at all, with contemporary interpretations of traditional Malaysian cultural forms, never dip into parochialism. The works could function in the context of any international gallery in addressing the medium to be read along side works by Gary Hill, Mary-Jo La Fontaine or Eder Santos.

Hasnul, who also heads the Fine Arts Programme at the University of Malaysia, Sarawak, curated the exhibition with Niranjan Rajah whose on-line work The Failure of Marcel Duchamp/Japanese Fetish Even! is available on http://wwwhgb-leipzig.de/waterfall/ [link expired]. The piece is a parody of Duchamp’s Etant Donnes which, in Rajah’s words, interrogates the ontology of imaging while marking the problem of cultural constituencies on the internet.

The historical component of the exhibition saw the mounting of a posthumous retrospective of the work of Ismail Zain, a veteran in the field of computer art. Ironically computer art was being produced by Zain and others in Malaysia before video art, which did not come until after computer art had been explored and developed. In producing collages reminiscent of early political photo collage, Zain said of his work “in digital collage there are no harsh outlines. The new medium is much more malleable, like clay”. (Noordin Hassan interviews Ismail Zain, Ismail Zain retrospective exhibition catalogue, National Art Gallery of Malaysia. 1995)

Ponirin Amin, one of the country’s leading printmakers exhibited a number of woodcut/computer prints, as did Dr Kamarudzaman Md. Isa. The strong traditions of printing, textiles and woodcutting saw these forms being integrated with computer generated elements to produce object based works, which ironically overcome the complaint among artists operating in the west have about the lack of collectability and therefore saleability of work in new media.

Other works included those by Wong Hoy Cheong, the Matahati Coterie, British, Kuala Lumpur-based artists David Lister and Carl Jaycock, a 3D animation using wayang puppets, screen and live performance as well as pieces from YCA (Malaysia’s Primavera) and winners from the Swatch Metal Art Award, Bayu, Kungyu and Noor.

RealTime issue #23 Feb-March 1998 pg. 25