The art of mobile phone empathy

Esther Milne on Larissa Hjorth’s Portrait of the Mobile

Larissa Hjorth, Snapshots: Portrait of the Mobile

At the opening of Larissa Hjorth’s exhibition, Portrait of the Mobile, there were the requisite gallery sounds of wine consumption and luvvie “m’waw m’waw” air kissing. There was also the whiff of incredulity: “so it’s just pictures of mobiles, then?” That sentiment is not, of course, anything new for the spectators of everyday poetics. Hjorth’s work participates in a complex and problematic tradition of art which attempts to represent both the banality and gravitas of quotidian cultural practice. As such, her show articulates key preoccupations of this tradition: presence, intimacy and display.

The exhibition is the result of a 6-month ethnographic project on mobile phone culture conducted recently in Seoul and Melbourne. Hjorth interviewed 150 people, asking 2 questions: “What does your mobile phone mean to you?” and “How have you personalised your mobile phone?”

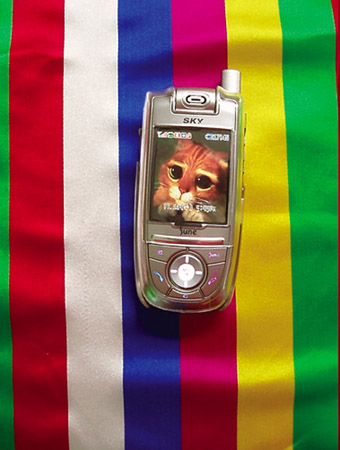

I have used a picture of my kitten as the wallpaper, and I like to hang gifties off it. Inspired by some artwork of a friend, I want to eventually have my phone laden with hundreds of crazy dangly things. I have also filled my phone with photos of everyone I love.

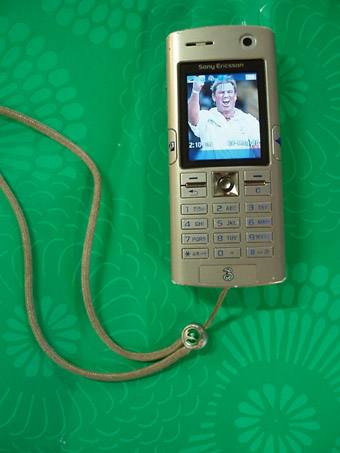

I’ve made my phone mine by putting my idol and Australia’s greatest ever cricketer, export and human being 😉 as my wallpaper …

These micro narratives comprise one component of the show, which is divided conceptually and materially into 3 zones. The survey responses, for example, are displayed as spinning lines of green text via a minimalist, sexy, flat screen monitor accompanied by a music track that could best be described as “symphony of elevator kitsch.” And here is where the visual and cultural logic of Hjorth’s work becomes evident. A productive tension inflects this exhibition between, on the one hand, the austere aesthetic conventions of gallery sensibility and the exuberant declarations of personal taste. Indeed, as Zara Stanhope observes in the catalogue essay, our attitudes to domestic space and personal technologies often manifest as “an Anglo-Saxon stoic resistance to all things kitsch and decorative.” This twin logic, one need hardly add, is also animated by gender. Just think of the marketing of mobile phones: forget about how they function, girls just need to fit them in their skinny jeans. In Hjorth’s work, both as art practice and academic research, we find a sustained critique about the gendered assumptions of mobile phone customisation and consumption.

Larissa Hjorth, Snapshots: Portrait of the Mobile

Occupying a second thematic and technological zone of the show are 6 photographs mounted on A3 size light boxes fixed to the wall. These large format duratran transparencies depict mobile phones in mundane detail, each set against a background of traditional Korean ‘rainbow’ fabric. Some of the images show mobile phones ‘open’ to reveal a variety of domestic, intimate and humorous screensavers: a couple in evening dress, a bug-eyed cutesy kitten and the aforementioned tribute to ‘Warnie.’ These images display mobiles singularly, in clusters and, in 2 shots framing the exhibit, in grid formation. All are personalised, some adorned with keyrings, animal charms and various articulations of everyday ephemera. Establishing notions of immediacy and presence as major preoccupations for this exhibition is the photograph of the camera phone displaying on its screen the time of 6.26. Echoing On Kawara’s famous “date paintings”, this image calls attention to the strong desire to archive the present within contemporary socio-technological communication.

As photographs of photographs and screen shots of screen shots, this exhibition functions simultaneously at the level of representation and meta-commentary. Let me hasten to add, however, this is defiantly not some po-faced, tortuous rendition of art theory 101. Hjorth has too much of a sense of humour for that. How else to explain the image of a mobile dwarfed in size and, one suspects, weight, by its attached robotic-looking bear charm. Yet there is also a luxurious quality, a luminosity to these photographs which owes its heritage to the light box.

Made famous, as Alison Nordstrom has explained, by Eastman Kodak’s Colorama installed at Grand Central Terminal in the 1950s, the light box has at its very inception, the display of domesticity. For more than 30 years, these huge advertisements (the light boxes were 5.5 metres high by 18 metres wide and required 1.5 km of cathode tube for illumination) celebrated the Norman Rockwell dream, literally and figuratively demonstrating the lightness of the American domestic being. As Nordstrom puts it “the coloramas taught us not only what to photograph but how to see the world as though it were a photograph” (Alison Nordström, Colorama, Aperture, NY, 2005). Too prosaic to be advertising, too domestic for the gallery, Hjorth’s mobile phone is re-imagined as object of spectacle. As Jeff Wall’s photographic work has shown, light boxes help stage the everyday image, infusing it with a theatrical and cinematic power.

If Hjorth’s work evokes the majesty of cinematic screen technology with its sweeping visual gestures, it also registers the intensity of the moment utilising, what Hjorth has elsewhere called, “the miniature and personal canvas of the mobile phone” (Cultural Space and Public Sphere in Asia conference, www.asiafuture.org). In the third zone of the exhibition Hjorth insists on the intimate force of presence in her 3 “mobile movies”: films shot specifically by and for the mobile screen. Titled Losing You, Lost in Connection and Snapshots of Almost Contact, these short films explore how connectivity is produced, desired and lost through technology. Drawing attention to the whimsy and nostalgia of the technological imaginary, Hjorth includes the skeuomorphic mechanical “shutter” sound effect as a character snaps a camera photo within the film.

Snapshots evidences Hjorth’s sustained fascination with the role played by domesticity and consumerism within mobile phone culture. This is her second photographic show dedicated to charting the ethnography of the familiar framed as the tension between hi tech and “domes-tich.” A deft exploration of the opposing sensibilities of measured aesthetics and flamboyant display, this exhibition is a bit like Philippe Starck and Hello Kitty duelling with mobile phones.

Larissa Hjorth, Snapshots: Portrait of the Mobile; Spacement Gallery, Melbourne, July 13-Aug 5

RealTime issue #75 Oct-Nov 2006 pg. 34