The art of multi-sensory care

Keith Gallasch: Interview, Efterpi Soropos, Human Rooms

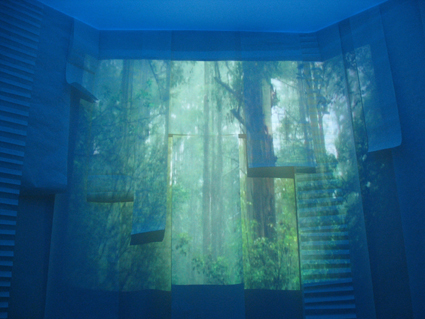

disambiguation room, Efterpi Soropos

image courtesy the artist

disambiguation room, Efterpi Soropos

Since training at NIDA in the 1980s Efterpi Soropos has created lighting designs for theatre productions around Australia, made her own installations and taught at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA). In recent years her focus has been on developing immersive artistic environments in palliative care after witnessing her mother’s distressing hospital experience when dying of cancer.

Soropos completed a Masters in Community Cultural Development, at the VCA in 2007 theorising about the alleviation of suffering in hospitals. In 2008 with an Ian Potter Cultural Trust grant she travelled to the UK and Holland for research. Out of this period came a prototype project at McCulloch House, Monash Medical Centre, titled the disambiguation room, commencing 2008 and funded by a grant from Arts Victoria, Community Partnerships.

The successful project by Soropos and her collaborators (see the artist’s website) became Human Rooms, an artistically driven commercial enterprise offering consultation, training and project development. Soropos was recently awarded a Churchill Fellowship. I spoke to her about the motivation for and the practicalities of her work and where it’s taking her next.

Where is your focus at the moment?

My focus has always come across as a bit vague, which is probably a typical way of seeing an artist’s outward persona. But I think I’ve discovered that it disguises a form of defiance and sharp analysis, which has enabled me to turn the disambiguation project into a permanent part of McCulloch House. It was always meant to be a temporary project and it’s now been re-designed and re-installed as a permanent installation. I’ve also developed a mobile version of the concept—a box that contains a selection of film images, sounds and lighting states that have been used in the original room, but now can be installed in a patient’s room.

My original intention with the project was to create a space for people to die in. And at the time, that was [seen as] just too out-there. So then I tried to find ways on a technical and practical level—how do you take that concept and put it into a space that a patient inhabits constantly, a hospital room? So I’ve been developing that concept and its commercial prospects. That artistic concept of Human Rooms can now be used by a variety of people in a number of spaces—in a home, a hospital, an aged care facility, a cancer centre, a palliative care centre.

How does the portable version work?

It’s a unit that has an immersive screen operated through wireless. I’ve developed an app so that patients, families or staff can set up the mobile version over a patient’s bed. This can be done in a shared ward where we know it’s very difficult to find peace or relax and, apart from painkillers, to reduce pain or psychologically find some way of being distracted or immersed.

What kind of images and sounds do you provide?

The basic concept of Human Rooms is built around immersion in a form of meditation with the sensory elements of image, light and sound either working in combination or as individual components. They find it engages them enough to precipitate some kind of psychological release. I’ve also used some animation based on simple, natural ideas, like cells re-forming and morphing which helps people to re-engage with, say, blood. These images can sometimes help people self-connect again if they’re feeling like they’re just a body with a disease in a hospital, or just a number and they’ve lost a sense of themselves.

What is the role of colour?

An Australia Council Inter Arts Office residency grant enabled me to work for a year with patients individually in rooms in the initial project. Sometimes women, for example, would prefer the room to be red. It made them feel like they were in a womb-like space or they were connecting with blood—maybe it’s because of our bodily function. Men might find red a colour of rage, or frustration, and they may have preferred the blue whereas women may have found blue cold. Colour is very subjective and also colour can bring up memories good and bad.

Mobile Immersion Unit, Human Rooms, Efterpi Soropos

image courtesy the artist

Mobile Immersion Unit, Human Rooms, Efterpi Soropos

So the app provides patients with choices?

Yes. When I hand these spaces over to staff and train them in how to use them, I always push the idea of creating something very soft or very subtle before bringing someone into the space. Then allow the person the opportunity to choose from the library. It’s all designed in such a way that the whole room [or the portable version] completely changes colour and the sound surrounds the listener. The rooms become…I was going to say ‘womb-like’ again but some people wouldn’t see it like that. The experience is very subjective.

Are institutions interested in buying into this?

I think it’s being viewed as another option. Medical staff are very limited in terms of what they can offer. A lot of hospitals have what they call ‘allied therapists’ these days. It’s all lumped under one category and includes everything from occupational to art therapy. Therapists can use Human Rooms for their work. I’ve trained pastoral carers, social workers and psychologists.

Have you completed this phase of your work?

I’ve probably completed it in terms of cancer care and palliative care. I’ve made these very subtle, integrated artworks. I’m now interested in developing a similar concept but at the other end of the spectrum, to create a bit of fun.

One idea is for a ‘playground’ for the elderly. In nursing homes there’s a form of multi-sensory therapy called Snoezelen, which was developed in the 70s in Holland by occupational therapists and psychologists who wanted to find a way to engage and relieve the anger and frustration experienced by people with special needs, using rooms that look like discos with the ball pits and coloured balls you see in playgrounds. They worked out that people with special needs responded to tactile and over-the-top visual stimulation. They’ve tried to move this into aged care to deal with people with dementia and Alzheimer’s. However, so that it’s safe, it’s a very one-on-one practice. I’m interested in developing a more artistic environment that engages people immersively but can be safely operated through apps and interactive panels. I also think that this would be suitable for kids with autism and Asperger’s.

Efterpi Soropos and her late mother Evangalia Soropos, 1987

courtesy the artist

Efterpi Soropos and her late mother Evangalia Soropos, 1987

How will your Churchill Fellowship help you?

I’m going to meet a variety of artists and health practitioners who are developing what we call MSE—multi-sensory environments—in the area of dementia in particular. I’m also very interested in culturally specific material—an adult in a dementia unit may revert back to the culture they came from. I’m going to Hong Kong to meet a group of artists who make culturally specific dementia projects at St Marks Hospital. I want to focus on one culture and see how the unit addresses this area. Artist Bellini Yu and the Art in Hospital organisation in Hong Kong work with sound, shadow and memory. I’ve been developing an online relationship with her and she’s also organised a workshop that I’m going to give to a group of artists she’s working with.

Then I’m going to London, firstly to King’s College, a major teaching hospital. Their new Marjorie Warren Dementia Unit has been completely designed for sensory input. So from when you walk in through the door, the colours on the walls and the flooring, all the finishes, the lighting, everything is designed for the senses. It’s beautiful. But they don’t use film, sound and lighting interactively as I do. I’ll also meet Anke Jakob, textile/projection designer/architect and researcher into MSEs at Kingston University. An aged care facility might want its staff or carers to have an understanding of what it’s like for a person with dementia to be in a nursing home, so the unit sets up immersive rooms that provide insight into what it’s like being inside the head of that person. These virtual environments are produced in Hull by She Knows Ltd, another Churchill destination for me.

What’s the attraction of Japan?

I will go to Japan, for the first time, to see the work of some of my favourite Japanese installation artists, like Eriko Horiki whose paper and light installations look to me like extraordinary spiritual spaces. On the opposite end of the spectrum I love the work of Chiharu Shiota who makes exquisitely dark memorials to life and death, covering inanimate objects and clothing in string that looks like a form of lace or a second skin. It’s delicate and fine but also kind of forbidding.

As an expert in your field and hoping to make a living in it, do you still feel like an artist?

The idea of what an artist does has now expanded in so many different directions. Heading into something like a commercial enterprise I still feel like an artist because I’m still able to come up with new ideas and be inspired by everyday things and people’s experiences. I had an epiphany when I was working on large-scale events in the 1980s and 90s—like the Mardi Gras parties. I was struck by the fact that people would go into an over-frenetic, loud and intense space to move as energetically as possible. But then when they needed it, they’d go into a chill-out space, calming them when they were very high, agitated or drunk. I knew there was something in that for people who had no choice in the state in which they found themselves.

Efterpi Soropos, Human Rooms, Experiential Art and Design, humanrooms.com

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. 4-5