the artist performed & painted

caroline wake, belvoir and big hart, namatjira

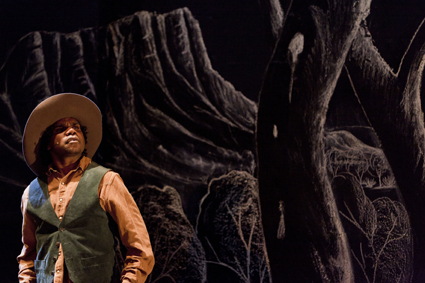

I HAVE NEVER SEEN THE MACDONNELL RANGES BUT TONIGHT THEY APPEAR BEFORE ME AS IF BY MAGIC. UPSTAGE, THE TWO BACK WALLS OF BELVOIR’S CORNER STAGE HAVE BEEN PAINTED BLACK AND COVERED WITH AN ENORMOUS WHITE CHALK MURAL DEPICTING THE RANGES AND THE GHOST GUMS THAT SURROUND THEM. WE ARE IN WESTERN ARANDA COUNTRY, THE HOME OF BOTH ALBERT AND KEVIN NAMATJIRA. THE FORMER IS THE FAMOUS WATERCOLOURIST WHO IS THE SUBJECT OF TONIGHT’S PERFORMANCE; THE LATTER IS HIS GRANDSON, AND AN ARTIST IN HIS OWN RIGHT, WHO IS ACTUALLY PRESENT, WORKING AWAY ON THE TEMPORARY WALL PAINTING FOR THE DURATION OF THE SHOW.

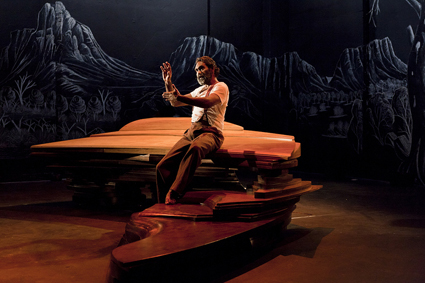

In front of these ghostly mountains, in the middle of the stage, is a large structure made of laminated wood that looks simultaneously like a deconstructed piano, an amorphous piece of public art and a section of undulating sandstone. Downstage is Trevor Jamieson, perched on a stool as the artist Robert Hannaford paints his portrait. The portrait looks well advanced but earlier production photos (see right) indicate that Hannaford started with a blank canvas, and like Kevin Namatjira, has been slowly adding to it each night.

Jamieson begins by introducing himself and his collaborators before sliding off his stool and telling the two seemingly unrelated stories of Albert Namatjira and Rex Battarbee. Namatjira was born as Elea but christened Albert by the Lutherans at Hermannsberg, where he stayed until he was in his early teens, at which point he returned to Arrernte country with his parents. Then at 18 he met and married his wife Rubina. Co-directors Scott Rankin and Wayne Blair throw the switch to vaudeville for this episode, with Jamieson as Albert and Derek Lynch as Rubina shimmying around the stage to Barry White’s “Can’t Get Enough of Your Love.”

This first story is intercut with a second: that of Rex Battarbee, a whitefella who grew up in Warrnambool until he enlisted to fight in the First World War. While away he saw England and France before being seriously injured and returning home. Towards the end of the act, Namatjira and Battarbee meet and become friends, with Albert showing Rex his country, and Rex showing Albert his watercolours.

In the second act, the story gains momentum, just as Namatjira’s life did, and we move briskly through his many successes: his first exhibition (1938); his entry into the Who’s Who (1944); the award of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation medal (1953); his meeting with the Queen herself (1954); and his attainment of citizenship (1957, a full 10 years before the referendum). However, success is bittersweet. Having money means that he has to support an extended family that numbers nearly 600 and having citizenship means that he has access to alcohol, which he is expected to share. When a woman dies on his property, it is he who is prosecuted because he is the only ‘citizen’ present. Namatjira is sentenced to six months hard labour, but after a public outcry is permitted to serve out the sentence at Papunya, where he eventually suffers a heart attack in 1959. The play finishes with his burial, and as we watch the man who has played him and the man who is descended from him stand in silence, it is as if we are witness to a second burial—the ghost of Namatjira is laid to rest in front of the ghostly mountains his grandson has conjured.

Beyond the impressive set (Genevieve Dugard), the principal pleasure of Namatjira is in watching Jamieson’s charismatic performance, as he slips between stories and characters, comedy and tragedy. Derek Lynch’s many sashaying women (black, white and a Queen to boot) are also enjoyable and Genevieve Lacey’s soundscape all-enveloping. The only false note in the evening comes after the curtain call when a stage manager reveals a small screen and we watch footage of the Big hART team working in the community. Presumably this is meant to reassure the audience about the nature of their engagement but it reads as both an odd sort of ‘reveal’ (and now, here are the real people) and as a pre-emptive strike against possible criticisms—one the production does not need since it is clear from both the program and the production itself that there has been not only consultation but also collaboration.

In a sense this collaboration echoes that of Namatjira and Battarbee, who apparently used to sit around in the evenings, talking about art, language and the world; two highly, if unconventionally, educated men, both of them globalised subjects before the word ‘globalisation’ even existed. This companionable image could serve as an analogy for the performance itself, for Namatjira is a convivial and thought-provoking night of stories, conversations and reflections.

–

Big hART and Company B Belvoir, Namatjira, writer Scott Rankin, co-directors Scott Rankin and Wayne Blair, creative producer Sophia Marinos, community producers Sia Cox, Pru Gell, performers Trevor Jamieson, Derek Lynch, artists Robert Hannaford, Kevin Namatjira, Evert Ploeg, Elton Wirri, musicians Nicole Forsyth, Genevieve Lacey, set designer Genevieve Dugard, costume designer Tess Schofield, composer and music director Genevieve Lacey, lighting designer Nigel Levings, sound designer Jim Atkins; Belvoir Street Theatre, Sept 25-Nov 7; www.namatjira.bighart.org/

Namatjira will tour to Melbourne, Dandenong, Geelong, Canberra and Illawarra from August 12 to September 30 2011. There are also plans for a national regional tour in 2012.

This article was first published online, Oct 12, 2010.

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. 33

–

Top image credit: Trevor Jamieson, Robert Hannaford, Namatjira, photo Brett Boardman