The Bank: the other photography

Esther Milne

Danielle Thompson, Night, The Bank Book

Banks are not defined by their aesthetic savvy, are they? Okay, sure—there’s the bucolic green withdrawal slip, clearly referencing 19th century evocations of the picturesque; those richly synthetic hues and fibres of branch carpets which quote from pop-art celebrations of plasticity; and not forgetting that sublime moment of transcendence when one finally hears a human voice while phone banking. But irony, startling colour and the pathos of narrative make this form of banking a properly aesthetic encounter. The Bank Book, as Helen Frajman’s foreword remarks, is not a collection of film stills. Rather, the project began as an invitation from the film’s producer, John Maynard, “to engage with the making of the movie” in a less commercially driven manner than usually the case with the film stills imperative. Through the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Maynard invited 4 photographic artists onto The Bank set to document, intervene with and comment upon relations between the media of cinema and photography. As Daniel Palmer notes in his introduction, “we do not need to have seen Robert Connolly’s film to appreciate these photographs. They exist…as a parallel project, with the photographers operating in the classic artistic role of ‘outsider.’” So although The Bank Book is not about adaptation—‘the book of the film’ in a Jane Austen/Amy Heckerling sense—it is about translation. Indeed, a visual arts review is always a translation since it is produced by that tricky process of ekphrasis: “the verbal representation of visual representation” (W.J.T. Mitchell, Picture Theory, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

Matthew Sleeth’s beautifully rich and cinematic images function simultaneously to pique and confound ekphrastic desire. In particular, the first photograph in his Light series makes expression a central trope by foregrounding a pair of gesticulating hands. Yet, straightforward communication is rendered problematic and the aporia revealed as (literally) veiled meaning since a billowing curtain obscures the backlit figure. Sleeth’s images—all chiaroscuro aesthetic and film noir sensibility—self-consciously explore the complex relations of photographic media, narrative construction and film genre. Instead of dames with slash-red mouths posing in cinched-waist dresses, Sleeth locates the technology of film noir as the object of scopic lust: long slender flood lights; dark ‘alleyways’ of thick cable; cameras bathed in shadow and reflectors drenched in rain.

Reflection is a dominant motif in Danielle Thompson’s intriguing yet incongruously named Brevity series. Bringing fresh perspective to reflection as one of photography’s oldest semantic devices, the first photograph is a study in screen iconography. Actors David Wenham and Greg Stone are shot through a car windscreen appearing fractured and fragmented. In a lovely metaphor for the filmmaking process, Thompson’s image is not so much concerned with reflecting the realism of narrative cinema, as it is to critique its underlying assumptions. And her photographs look beautiful. While the term ‘brevity’ captures something about the spontaneous nature of Thompson’s work, this title belies her lyrical articulation of very different rhythms. Measured and mediative portraits of the actors function almost in counterpoint to other blurred and ephemeral images. As if to dwell on the temporality of this series, one photograph foregrounds an inverted ‘SLOW’ traffic sign.

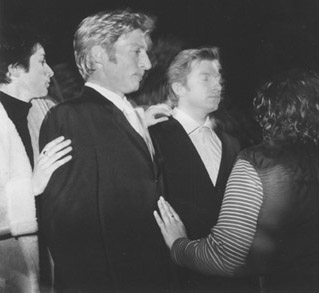

Translation as re-presentation is a central thematic of Peter Milne’s (no relation, just an ex-husband) photographic art practice generally and is specifically at play within these images. His witty collaboration with Helen Frajman titled Amended Shooting Script is a re-working of The Bank’s original screenplay. The film script has been physically chopped up and juxtaposed with flash-lit black and white photographs of the cast and crew at Anthony LaPaglia’s farewell party. By superimposing snippets of fictional narrative onto ‘real’ interactions, Milne and Frajman bring 2 spheres of representation into uneasy collision. A tension emerges between those who would translate print into image (the cast & crew) and those who attempt to interpret the interpreters (The Bank Book photographers). And as always with Milne’s photography, this series has a haunting quality: an initial laugh followed by what Roland Barthes calls the ‘punctum’: those unexpected and disquieting moments of photographic art.

One of the troubling and compelling aspects of Max Creasy’s work, as Palmer notes, is the almost total absence of the human form. The series Flats subverts key assumptions about the generic demands of narrative realism by leaving out ‘characters.’. Instead, Creasy gives us a self-referential and playful translation of the ontology of character itself. In one of his images, black and white PR shots of the stars are taped to a wall inviting us to join the game of the mise en abyme (photographs of photographs of photographs ad infinitum). In place of the usual stability we expect of realism, Creasy gives us vertigo: the metaphor of infinite regress is enacted by the refracting and reflecting mirrors, screens and windows appearing in his images.

The screen as translation technology functions as an overall thematic for The Bank Book. Yet, as is always the case with ciphers, this is not a transparent or innocent process. A point dramatically made by Thompson’s image of David Wenham and his stunt double, these artists have produced an enigmatic study of photography and its others.

The Bank Book: Photographs by Max Creasy, Peter Milne, Danielle Thompson and Matthew Sleeth, edited by Helen Frajman with an introduction by Daniel Palmer (M.33: Melbourne 2001), 104 pages, 260 x 240mm, $55.00, ISBN: 0 9579553 0 8. Ordering information: email, tel 02 9319 7011.

RealTime issue #47 Feb-March 2002 pg. 26