The Bluebird Mechanicals: This toy world

An addendum to a Chekhov play melds with the last moments of the Hindenburg airship and the inner psyche of windup birds to cumulatively explore the winddown of the world in The Bluebird Mechanicals.

Writer and performer Talya Rubin opens by pouring water into a glass diorama containing a toy writer at his toy desk. The tiny figure at a typewriter is trapped, immersed. This drowning-in-miniature is projected live on stage, a small tragedy broadcast and made grand in scale.

Rubin then weaves her way through the audience, asks if we’ve ever seen a Chekhov play, perhaps even a bad one — The Seagull, at school, she suggests, with a knowing nod. In any case, she’s about to rewrite the ending.

It transpires that the playwright Konstantin in The Seagull, troubled by his unrequited love for Nina, an ambitious actress who rejects him for a more successful writer, has written a play about extinction. Rubin and her collective Too Close to the Sun take up the Chekhovian narrative after Konstantin’s suicide. We are privy to imagined exchanges between the jilted writer and his ex-girlfriend, the makeup conversations that lovers Nina and Konstantin didn’t get to have. Rubin as Nina, like the submerged writer, inhabits a life-sized glass cabinet for these scenes. In this living diorama she is visited by a ghost, pursued by an owl and rows with the dead playwright on the lake that was central to their relationship. There is, in the end, with Nina’s drowning in the lake, a sort of watery transcendence compared with Konstantin’s offstage death in Chekhov’s play. At the same time The Bluebird Mechanicals offers Konstantin a voice beyond the grave, and more depth to the pair’s relationship.

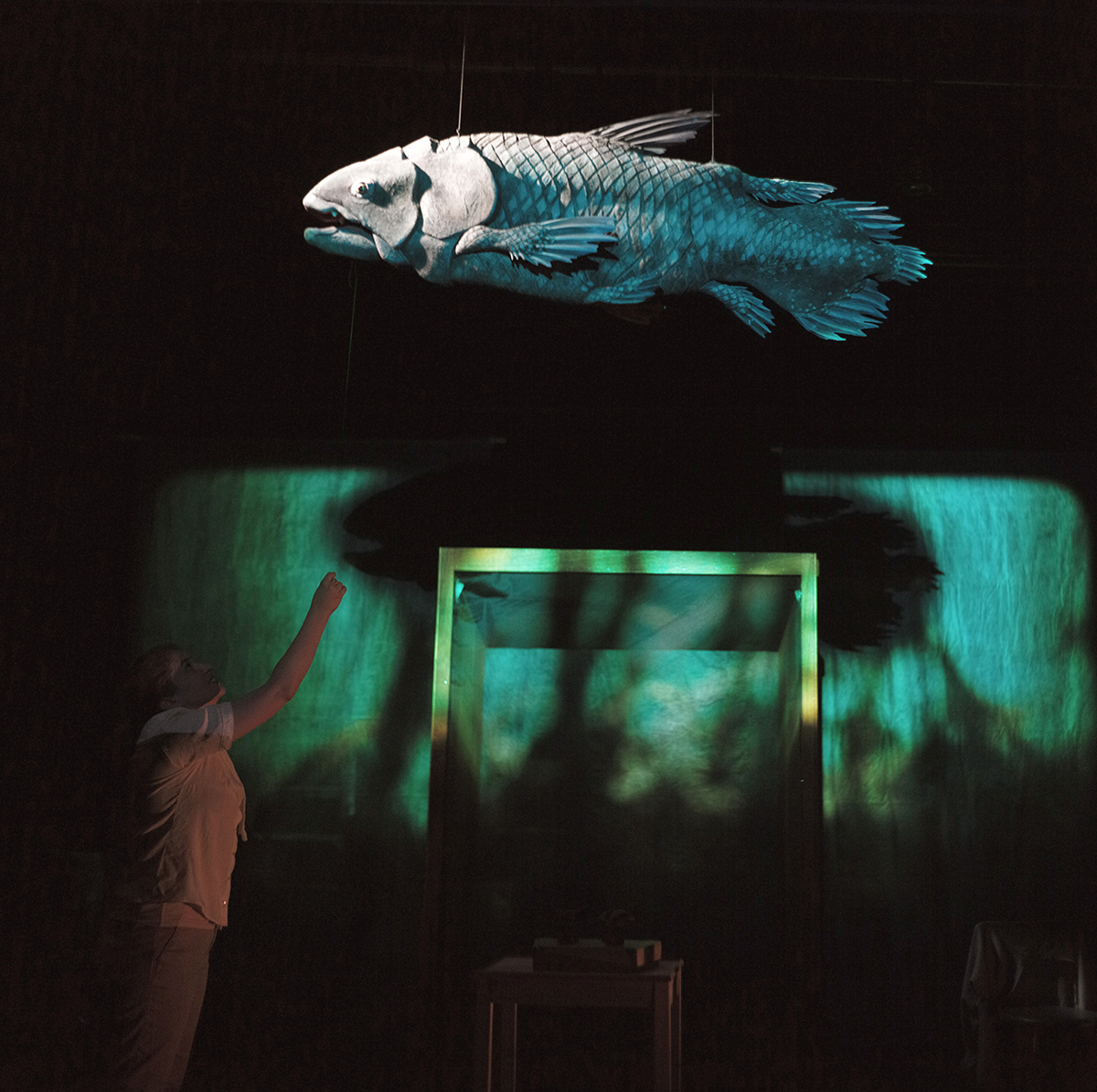

The Bluebird Mechanicals, photo Samuel James

In between these scenes, Rubin confides that she’s had a dream about the ill-fated Hindenburg, the famous airship disaster of 1937. She can’t shake the idea that she has been destined to make a show about it. She transforms into a cynical and snarly Hindenburg tour guide, treats us to a slideshow of the attractions offered by the luxury blimp and suggests a glass of sherry, perhaps to sedate us as we hurtle towards oblivion.

It’s the toy bluebirds in the production that steal the spotlight when brought to life by Rubin. She listens, allows them to speak, and as their voices emerge — one is a fatalist while another is almost inanely positive — so too do their opinions on climate change. Bird brains they are not and though struggling with human speech they indicate humanity is “too stupid” or in too much denial to acknowledge that it is going down with the ship. The icebergs are melting, the waters are rising and we come to understand that we, collectively, are the Hindenburg, an overinflated folly headed for disaster. Diversions like off-blimp excursions and luxuries like crystal stemware will not save us, not then and not now.

And so The Bluebird Mechanicals unfolds, its imagery and layers of meaning interwoven and patterned as intricately as forms found in nature, like a school of fish or a flock of birds. The wunderkammer as linking device is well realised; the scenes are all animated from the inanimate — dioramas composed of lush landscapes and taxidermy or toys, miniatures and symbols of the natural world that together form a wunderkammer across the stage.

The Bluebird Mechanicals, photo Samuel James

The work flickers between the Chekhov, the Hindenburg and the birds towards an inevitable end. The vignettes are like shooting stars, each a luminescent moment in the dark. Sometimes though, these are over too quickly and we are left waiting in blackout while the set is adjusted, the transitions clunkily inhibiting the flow.

The joy of this work is felt in the performance and design. There are exquisite moments: a windup bear is set loose in a model forest, complete with powdered snow. This is projected as well, showing us that microcosms and the epic may coexist and suggesting there are always bigger concerns beyond our own. The sound and lighting design are precise and Talya Rubin is a mesmerising artist to watch, even in stillness, slipping uncannily and effortlessly between characters.

There is also a fourth character knitting the threads of this work together, a European woman who lives alone in a vast city and who reminds us of the many ways we have betrayed our planet. She’s a kind of seer, a sage who dares name what we do not. Towards the close, she tells us she had a vision of an urban world cracking open, the figures on the street like toys toppling into a void as the end came. If the Earth was just that, a toy world, then the damage we have done might not feel quite so devastating.

–

Too Close to the Sun, The Bluebird Mechanicals, writer, co-devisor, performer, visual concept Talya Rubin, co-devisor, director Nick James, sound designer Hayley Forward, lighting designer Richard Vabre, video designer Samuel James, set consultant Corinne Merrell, object/miniature designer Nancy Belzile, object/miniature makers Caitlin Ross, Alizee Millot, set builder, cabinet designer Mark Swartz; Metro Arts, Brisbane, 7-16 Sept

Top image credit: Talya Rubin, The Bluebird Mechanicals, photo Samuel James