The body: sensual, recollected and phantasmic

Jonathan Marshall: Bodyworks 03

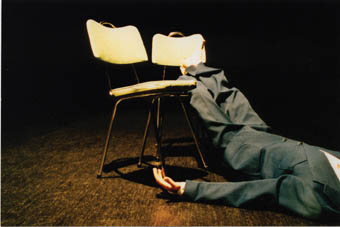

Phillip Gleeson , The Follies of Emptiness

Dancehouse curator Helen Herbertson’s Bodyworks 02 was a showcase of well-developed, inspired works from Rosalind Crisp of stella b, Tess de Quincy, and Phillip Adams of balletlab. By contrast the 2003 program largely consisted of modest pieces at earlier, tentative phases of their development. Martin Kwasner, Tim Davey, Rakini Devi, Eleanor Brickhill and Phoebe Robinson presented fine studio studies containing compelling elements or moments, but none was cohesive or satisfying in overall form. Sue Healey’s Fine Line Terrain also had a searching inconsistency for the opposite reason, it was adapted from several longer studies with more dancers and a complete design. Although Bodyworks 03 reinforced Dancehouse’s position as an institution promoting catholic, innovative choreographies, it remains unclear if Bodyworks is an annual ‘showcase’, or a more experimental season.

The uncertain, sketchy quality of Bodyworks 03 meant that those pieces developed from a strong, cohesive idea, or which self-consciously grasped and worked with their own play and ebb-and-flow were all the more impressive. Born in a Taxi for example presented a superb structured improvisation, using general yet stringent narrative and characterisations on which to hang exuberant yet often vaguely melancholy clowning and movement. Although The Potato Piece was new, performers Penny Baron, Nik Papas and Carolyn Hanna have worked together for years and so the project represented a more evolved showing of their established physical, dramatic style.

Michael Nyman’s lightly pulsating, neo-Baroque music helped emphasise the Peter-Greenaway-esque, tangibly sensorial nature of the production. Simple set elements such as heavy, wooden boxes and planks, a pile of rough tan-bark, water, textured hessian and garden produce-potatoes, apples and oranges-solidified the show. It also made it as much about the audience’s empathetic identification with the performers-smelling fruit, discovering new tastes and textures, or settling to work seated upon cool, upturned tin pails-as about any overt narrative or character development. Three figures, each associated with a particular fruit or vegetable, moved from isolated introspection and self-devised physical rituals, to meet, exchange produce and gestures, and sort through their collective materials. The performance was like a quizzical coming-to-life of a still-life, complete with the glistening, painterly patina of ripe, cut fruits and warm lighting by Nik Pajanti in the style of the Dutch masters; a sort of opera buffo in Buster Keaton style physical game-play and dance.

The show concluded with the characters’ discovery of books amongst their surrounds-another element from the tradition of late Renaissance still life. This final device led to a delightful sequence in which each performer stood on a heavy, oaken cube, gesticulating and physically relating the tale that they had just read intently to themselves. However this sequence was less well integrated into what preceded it, the characters failing to return to their central, identifying props (potatoes, apples, oranges), closing with an explosion of business largely unrelated to the motif of the 3 growers. The Potato Piece was nevertheless a thoughtful, joyful performance.

Dianne Reid’s Scenes From Another Life also sustained a sense of comic play. For Reid however, this was tied to an interest in her own self as a form of remembered, public performance. Reid’s physical intonation exhibited a quality common to several of Melbourne’s mature independent dance-makers (Sally Smith, Felicity MacDonald, Shaun McLeod, Peter Trotman). Although her apron-like costume and clearly-defined musculature evoked Chunky Move’s young dancers, Reid and her peers have abandoned the exploration of physical extremity as a device for developing choreography. Reid performed with more of a sense of the everyday and with a wonderful softness and lightness, which made the sudden lilts of strength and precision that come with a dancer’s body all the more charming.

Using text, music and projection, Reid explored the uncertain body of the public performer. Unlike the more conceptual, linguistic model developed by choreographer Simon Ellis in Indelible (see RT 54), here memory was inherently psychokinetic, melding pleasure, discomfort, hallucination and the physically remembered past in the act of recalling events. While Ellis clinically yet evocatively rendered the idea of memory, its structures and its conceits, Reid amusingly depicted the psychophysical experience of finding one’s body suffused with the quirks of recollection.

Tiny, projected versions of the performer clambered and tumbled over her torso as she looked on, disconcerted by this bodily revolt, yet also lovingly empathising with her diminutive other selves, helping them over her shoulder with a gentle push or lift from under their feet. Reid explained that she wasn’t even sure if these and other remembered gestures and songs were her experiences or moments from films she’d seen, or stories she’d told. As the show’s title indicates, the body and our sensory memory constitutes another life, including dreams, awkwardness, yet also our pleasures and our most comforting personal sensations. Reid concluded that the bemused confusion she felt about the source of these impulses and sensations mattered less than the idea that one can recall with absolute certainty such mundane feelings as “stretching out on your stomach, in the sun, like a cat.”

The highlight of Bodyworks 03 was director Phillip Gleeson’s The Follies of Emptiness. Ben Rogan’s most notable performance trick is a roiling of his abdominal organs and musculature to represent psychophysical disorder and alienation. Under Gleeson’s guidance though, Rogan’s form became a microclimate of electric ripples and erratic tremors. Gleeson’s lighting created an environment in which Rogan and Trudy Radburn’s bodies melded with wavering tangibility sustained by Expressionist aesthetics (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, Pandora’s Box etc). By using barely perceptible, misty illumination, juxtaposed with brightly-focused points of light hovering in darkness, Pajanti helped render the performers as semi-decomposed, textured phantoms, unfixed within the audience’s perception of space and depth.

Emptiness was not, however, a neo-Expressionist homage, despite its superficial visual similarity to that dark scion of illusionistic, vaudevillian cabaret. The show was characterised by a more viral sense of mutation and interaction. Jen Anderson’s exquisite, scintillating sheets of noise drew on some relatively ‘popular’ music such as Aphex Twin and Einstürzende Neubaten, but overall the score sounded similar to contemporary French electro-accoustics like those on the label Les Emprintes Digitales. The turbulent, musique-concrète-crazzle echoed and reinforced the sense of an explosion of sensations outwards and inwards-of bodies and personalities absorbing and projecting everything from cheap, electrical lights to hissy 1960s tango-pop; from the lurid, luminescent orange wallpaper Radburn absent-mindedly sashayed before, to the vinyl and chrome kitchen chair Rogan fused with, spider-like. Just as the score sometimes resonated with a sudden backward sweep of magnetic tape sound, one had the occasional impression, watching Rogan and Radburn, of viewing videotape in rewind.

There was a bleed-through of signals, influences and emotions, a mutual contamination of sparse, thematic elements that made the few moments of robotic, automatic movement seem more akin to a wildly visceral form of wet-ware, virtual reality (which of course it is), than the now venerable idea of Cartesian, mechanised life. As in David Lynch’s Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive, or even Jean Luc Goddard’s more raggedly inter-cut work, the very DNA of character and emotional ambience here became subject to spontaneous change, producing an uncontrolled, hypnotic sense of instability at every level. This jumble of references created a deliberately abstruse portrait of weird, (sub)urban, formlessness, or domestic cyberneticism. Emptiness was particularly impressive in this respect, given that Gleeson eschewed almost all of the touted, glossy tools of contemporary new media normally employed to achieve such effects within his own rich yet minimal dramaturgy.

Bodyworks 03, curator Helen Herbertson, lighting Nik Pajanti, John Ford, Dancehouse, Melbourne, Mar 12-30; The Potato Piece, Born in a Taxi, devisers/performers Penny Baron, Nik Papas, Carolyn Hanna, direction Tamara Saulwick; The Follies of Emptiness, director/choreographer/lighting/set Phillip Gleeson, performers Ben Rogan, Trudy Radburn, Max Beattie, music & sound Jen Anderson, Kimmo Vennonen; Rust, performer/choreographer Martin Kwasner, dramaturg Tim Davey, text Allan Gould; The Dusk Versus Me, performers/choreographers/projection Tim Davey, Katy MacDonald; Q U, performer/choreographer Rakini Devi, percussion Darren Moore; Scenes From Another Life, performer/choreographer/video Dianne Reid, costume Damien Hinds, dramaturgy Yoni Prior, Luke Hockley; Waiting to Breathe Out, performer/choreographer Eleanor Brickhill, performer Jane McKernan, music/text-performance Rosie Dennis, lighting Mark Mitchell; The Futurist, choreographer/performer Phoebe Robinson, music Tamille Rogeon, sculptures Alex Davern; Fine Line Terrain, choreographer Sue Healey, performers Shona Erskine, Victor Bramich, music Darrin Verhagen.

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 39