the city dances

keith gallasch & virginia baxter at a celebration of dance

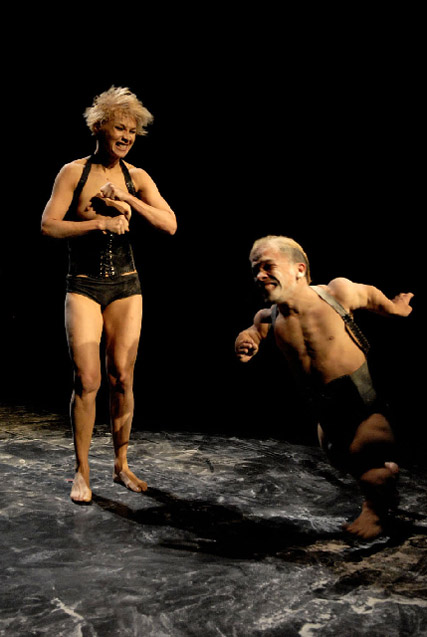

Ballet de l’Opéra de Lyon, Superstars

photo Michel Cavalca

Ballet de l’Opéra de Lyon, Superstars

LYON’S 2006 IMMERSIVE BIENNALE DE LA DANSE IS its TWELFTH. THEMED AROUND THE EXPERIENCE OF LIVING IN CITIES IT IS STAGED in an AMIABLE CITY IN LOVE WITH DANCE. WE WITNESSED ONE WEEK OF A THREE WEEK DANCE PROGRAM THAT EMBRACED THE WHOLE OF LYON, FROM THE CENTRE TO THE SUBURBS AND SURROUNDING REGIONAL TOWNS AND A COMPLEMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHIC EXHIBITION, DES CORPS DANS LA VILLE (THE BODY IN THE CITY), INVOLVing 32 GALLERIES, FROM IMPROMPTU SPACES TO THE MAGNIFICENT LYON MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART.

In turn the dance biennale was embraced by large audiences from the city to its the periphery, for example at Le Toboggan, an impressive arts centre where we saw Australia’s Force Majeure play to a receptive full house on the last of its three packed performances. The Sydney-based company, directed by Kate Champion, was the first Australian company to be invited to the Biennale.

The intensity of this festival of dance and its public involvement was more extensively revealed in the Défilé—a 3 hour pageant in which some 24 groups of citizens from the suburbs and surrounding towns displayed a range of dance styles on and around floats often incorporating musical performance involving DJ-ing, contemporary brass bands playing fine progressive compositions, and found object ensembles (favouring large plastic water bottles). Each group works with a choreographer and designer, is funded by the city and draws on additional resources according to its ambitions. The makeup of the groups ranges across age, ethnicity and ability and all made good use of the metres of material supplied by local manufacturer sponsors in a region famous for its textiles. Each group presented a commentary on the idea of the city—utopia, distopia, fantasia—employing diverse devices, forms and images—cycling, recycling, modern dance, hip hop, art history (the Bauhaus body as city) and the history of city clothing, from elegant medieval to 20th century Chaplin, to hip hop armies and sci-fi glitter and transparency. Public fancy dress inventiveness was also on rich display at Bal Bollywood, an evening of Bollywood dancing DJ-ed, performed and taught from the stages of a massive suburban nightclub.

Lyon’s Biennale de la Danse emerged in the early 80s from the vision of the director of the city’s Maison de la Danse, Guy Darmet. Darmet’s energy, charisma and the biennale itself are said to have convinced the citizens of Lyon once and for all that they are not the dour cultural inferiors of Paris but the Latins of France. This was in evidence as this easy-going city threw itself into Défilé and Bal Bollywood and packed theatres and studios for the wide-ranging dance experience programmed by Darmet and Assistant Programmer Sylvaine Van den Esch.

We arrived in Lyon when the festival had been underway for a week, and after our departure there were companies like Les Ballet C de la B we regretted having to miss. Even so we had a packed program, sometimes seeing several shows a day but even then finding by word-of-mouth that we’d missed something significant, for example architecture-trained Julie Desprairies’ (Compagnie desprairies) site-specific performances, Là commence le ciel. In Desprairies’ work people are incorporated into nature, buildings, freeways; bodies become part of their environment. The word was good also on Tokyo choreographer Kim Itoh’s take on a butoh classic, Kin-Jiki, and Nacho Duato’s Multiplicite: Formes de silence et de vide for his Madrid-based National Dance Company. There was a lot of excitement about the eight-strong local Pockemon Crew who’d been “taken from the portico of the Lyon Opera House to the Maison de la Danse.” The portico has become a permanent public venue for hip hoppers and break-dancers as audiences weave their way to performances in the house.

The Lyon Opera House is a 1756 building in the heart of the city strikingly renovated in 1993 by Jean Nouvel who also designed the Musee du Quai Branley in Paris. Here he added a new arched steel and glass upper level housing, amongst other facilities, rehearsal studios looking out over the city. Nouvel’s interiors have a rich, dark, immersive quality: black marble; escalators; metal walkways; an ominously bulging fibreglass sculpture like a black cloud; and the whole place suffused with soft orange light. Oddly, the same orange stares at you from a bulb in the back of the seat of the person in front of you in a theatre with a huge stage but an intimate auditorium with six levels of shallow balconies, the whole mostly in black and with a gun-metal sheen.

Ballet de l’Opéra de Lyon, Superstars

photo Michel Cavalca

Ballet de l’Opéra de Lyon, Superstars

ballet de l’opéra de lyon: rachid ouramdane

We’d heard that Yourgos Loukos, Director of Dance at Ballet de l’opéra de Lyon, runs a strong program, consistently inviting, progressive choreographers work with his dancers. Loukos writes, “although a classical formation, (the company) is oriented towards contemporary dance; given the wide range of dance styles proposed, the artists acquire many different techniques”. In a typical year, guests include Trisha Brown, Mats Ek, De Keersmaeker, Russell Maliphant, Sasha Waltz.

But the choice of young French choreographer, Rachid Ouramdane, for the Opera’s contribution to the Biennale was seen as particularly bold. Ouramdane’s Superstars shared the bill with New Yorker Tere O’Connor’s Creation.

In Superstars, a massive white box fills the huge stage littered with six Macintosh computer screens of different sizes and two white loud speakers. Guitarist Alexandre Meyer, also dressed in white, mixes his own sound from the side of the stage and traverses it as he plays. The work is a series of solos in which the dancers from the Opera Ballet express aspects of their lives. The challenge for us was that most of the speech was French without surtitles. A subtle force slowly flows through the poised body of the first dancer, vertically and then horizontally. Suddenly she speaks, in French, then briefly in English about the challenge of growing up white in South Africa, her words punctuated by great chiming guitar chords. Rapid upper body movements parallel her account of living with an albino sister in a culture distinctly black and white; hearing the everyday sound of rifle shots; sensing the power of an otherwise disenfranchised black culture when you’re the only white family in the district; and attending a Whites Only school. And learning what fear is. The dancer conveys a strange kind of stability as she vibrates with remembered trepidation. This dynamic sculpting of the standing body seems the foundation for most of the solos that follow and it’s matched by the architectural feel of the design, of a space slowly transformed by bodies and soft waves of coloured light (Jean-Michel Hugo) emerging from unexpected points of the space. Instead of elaborate dance we witness states of being. Overall, Superstars didn’t appear to head in any particular direction, each piece seeming complete in itself even where overlapping.

These solos by members of the resident company were based on childhood recollections and ranged through a variety of images including sport and cross-dressing. One of the more striking was of an angular, statuesque dancer in red holding her body in difficult poses for long periods, then lying on the floor, arching her back high to an organ-like guitar composition, the light narrowing into a pool around her. The show stood magically still. Superstars was a provocative work; despite the language challenge, it remains strong in the memory.

Tere O’Connor’s Creation also started out with a strong architectural feel, a large mass of bodies forming a block beneath a suspended row of dense curtains, another block of the same proportion. Small variations in group patterning and individual moves evolved in the crowd in various permutations of placement and displacement against the mutating design. But, disappointingly, Creation dissipated into something more waftily generic replete with literal game-playing, robotic moments ending with some very formal dancing against uninteresting flown-in wallpaper panels.

force majeure

We travelled to Force Majeure’s Already Elsewhere in the free bus to the theatre provided by the festival. On our way to Le Toboggan (Centre Culturel Ville de Décines) the landscape changed from old inner city to high-rise to two-storey suburban buildings till we were on the rural outskirts of the city. Force Majeure were programmed as part of the Centre’s 06/07 Saison Eclectique. Le Toboggan was but one of the performing arts spaces we encountered on our visit to Lyon that program boldly. The venue was spatially ideal for the work. Audience members and reviewers we spoke to were responsive to the concept, the design, the stylish realisation of the work and the skill of the dancers. For us it was good to see the work for a second time and with a very different audience and to admire its most sustained sequences, like the dynamic but nonetheless lyrical race of performers across the rooftop in pursuit of Kirstie McCracken, teacup and saucer in hand. The decision to translate substantial amounts of the spoken text (delivered by Veronica Neave) into French paid off. Already Elsewhere perfectly fitted the biennale’s theme of the body in the city, bringing a distinctly strong element to it, the sense of the suburban and the fragility and everyday fears of urban life.

cie l’explose

Cie L’Explose, Frenesi

photo Michel Cavalca

Cie L’Explose, Frenesi

Cie L’Explose from Colombia, performed Frenesi, choreographed by Spanish born Tino Fernández. Although inspired by bull fighting, the corida, this doesn’t become literal until the very end when a male dancer finally dons the costume of the matador and even then it’s symbolic. The work begins abstractly in the ritualised dressing and undressing and preparing of male bodies for an unspecified event. Four women lift and turn four naked men on gurneys and dump them unceremoniously on the floor. The first to come to life is a man of short stature whom the women dress in leather belt and buckles while the other men gradually dance to the sound of flamenco clapping. The short man topples the others and is subsequently involved in a cleverly sustained duet of pursuit and entwinement with one woman and a frustrated attempt to engage with another who stamps a raw, vibrating flamenco. He collapses, defeated. The women oil the men, their limbs hanging limply from the gurneys like scenes from some Francis Bacon butchery. Finally one emerges, slips into matador pants and dances triumphantly over a naked woman rolling downstage to us, raw meat tied to her body. Despite or maybe because of its curious sexual politics, but moreso because of its dramaturgy, Frenesi is an intriguing experience, offering a version of men, or rather one man, raised from the abject to the triumphant, overcoming women (and men of short stature). The bull no longer represents the horns of the male’s ambiguous relationship with the forces of nature—there are other more urban and domestic forces to contend with. The choreography was idiosyncratic, the manipulation of bodies almost always interesting.

Seeing this performance primed us for our first foray into cuisine Lyonnaise—mysterious meats preceded by very good oysters and washed down with a genteel Cote du Rhône.

atelia de coreografia

A less engrossing dance experience was to be had from Rio de Janeiro’s Atelier de Coreografia in ExtraCorpo, choreographed by João Saldanha. In the intimate Le Rectangle, we sat stiffly around the edges of a white space to experience an extremely formal set of variations with accompanying abstract gestures. Initially bodies appeared almost statue-like with limited fluidity, small spins and falls until, gradually, an increasingly flexible geometry emerged. This was a work of high modernism inspired by the choreographer’s association with Oscar Niemeyer, the architect of Brazilia. In comparison with Frédéric Flamand’s Metapolis 2, seen later, the relationship between architecture and choreography seemed vague at best. Occasionally there was welcome additional detail from two of the younger female dancers whose textured, rippling movements suggested something more than stark abstraction. The accompanying recorded music was suggestive of a dense primordial soup as the work moved towards its more complex, agitated conclusion.

selenographica

A cluster of smaller shows included Kyoto’s Selenographica in What Follows the Act in which the choreographer Maho Smiji appears in a chamber work of domestic surrealism, performing with Shuichi Abiru and an accompanying musician on flute and recorders in the western manner. This awkwardly staged work was eerie and quaint by turns with some resonances with the Noh play and Japanese ghost stories.

noland

Death also figured thematically in Noland’s Paper Ship. The young company from Istanbul fused an elegy for a dying patriach with a celebration of an emerging romance framed by city life. Dancers Esra Yurtlut and Alper Marangoz and video artist Burak Kolcu have created a work of modest scale, indistinct choreography and loosely integrated video images of Istanbul. Although the storytelling was at times overly literal there were some strong moments when bodies became entangled or toppled into each other, the characters struggling simultaneously with loving and grieving.

ballet national de marseille

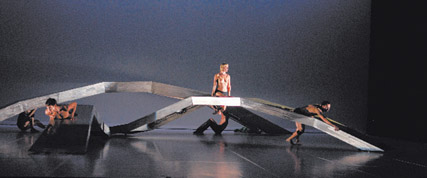

Ballet National de Marseille, Metapolis 2

photo Michel Cavalca

Ballet National de Marseille, Metapolis 2

Metapolis 2 is a fresh interpretation of an earlier work, Metapolis 1 by Frédéric Flamand, first performed in 2000. Flamand was formerly the director of Belgium’s Charleroi/Danse-Plan K but has taken over the Ballet National de Marseille.

For Metapolis, the internationally renowned Iraqui-British architect Zaha Hadid designed two mobile, asymmetrical bridges to be moved about by the dancers, to provide platforms but also spaces in which to insert performing bodies, as well as for the bridges to intersect, one riding over the over. The sheer scale of work is impressive: a large ballet company with seemingly unlimited means using architectural creations in conjunction with new screen technologies. The entire back wall forms a screen amplifying massively the movement of a foot straining against the slope of a bridge, or displaying the rush of filmed city streets against a running phalanx of onstage dancers matching the speed of vehicles. Images (some recorded, some live) are also projected onto the bodies of the dancers absorbing the city into their green-screen costumes. A male dancer lies on a green sheet on the floor, his movements projected onto the screen image of a traffic tunnel so that he appears to fly effortlessly through it. Dancers appear to fall into holes in the city.

Although Metapolis II reproduces much of what we know of the city experience—speed, congestion, mutability, vulnerability—and evokes its imprint on our lives as image and as states of being—alienation, romance, adventure—the sheer scope of the work, the number of scenes and devices threatens to make for a rather generalised response. What city? Any city. Likewise the ever graceful, fluent dancing within a framework that is often geometrically formal threatens sameness. Flamand has yet to invent a language as idiosyncratic and contemporary as Forsythe has for his ballet-trained dancers. However there are solos and duets and small moments of drama that break the mould, as do the sudden images that offer unexpected and privileged views of the city. A slice of city is projected on a dancer’s huge skirt while he is in turn projected, slowly turning 360 degrees, onto the big screen in a vertiginous dance of actual body, virtual body and camera eye.

In Metapolis II’s climactic scenes, black and white footage of street riots and demolition are screened, the dancers mounting Hadid’s bridges and watching—Flammand drawing, he says, on a Tiepolo painting of people looking into a world that frightens them. The work ends energetically and optimistically, maybe ironically, with energetic ensemble dancing against a fast trip through a huge digital city.

farruquito y familia

Our surprise festival experience was Farruquito y Familia. Although not usually enamoured of flamenco dance, we found ourselves swept along by this pared back Gypsy version of the form with its dressed down, raw power, precision, humour and informality. Juan Manuel Fernandez Montoya ‘Faurruquito’, still a young man, leads the family ensemble he inherited from the great Farruco (1935-1997), dances exquisitely, sharing the stage with brother and cousins and not least with his aunt and his mother, who arrives on stage late in the show with all the presence and power of the matriarch. Young local gypsies from the audience joined in the encore, a young girl in their number stamping in sneakers, dancing with complete confidence to riotous applause.

isabella’s room

Needcompany, Isabella’s Room

photo Eveline Vanassche

Needcompany, Isabella’s Room

Belgium’s Jan Lauwers sees himself as “a man without a city”, so it’s not surprising that Isabella’s Room appears not as rooted in the biennale’s city theme as other works, and starts out, at least in its storytelling, in a lighthouse, “an inbetween place; somewhere between land and sea”, where Isabella is born. Lauwers and Needcompany’s show is a very lateral take on 20th century history and the very long life of one woman, Isabella. Two cities do aptly figure, Paris where Isabella finds some respite from personal trauma among the cultural objects brought back from colonised Africa, and Hiroshima where a lover witnesses the appalling pain and devastation of the H-bombing.

Isabella’s Room is a marvel of the undoing, hybridising and remaking of theatre. In a press conference Lauwers, who appears in the production in a white suit, playing guitar and joining in the dialogue and the dancing (and what dancing, joyful and mad), confessed surprise at having created a musical. Not a bad thing, he thought, reflecting on the dark Needcompany works of the 90s and sensing a need for an antidote, albeit a critical one, to the current grimness of the world. So, Isabella’s Room is full of singing and dancing along with dialogue played directly and intimately to the audience amidst Lauwers’ collection of anthropological objects inherited from his recently deceased father. (In what curious ways is Lauwers himself Isabella?) The company’s self-choreographing dancers (Julien Faure, Ludde Hagberg, Tijen Lawton, Louise Peterhoff) spring into idiosyncratic action either on their own or draw in the whole company, or provide upstage counterpoint to downstage dialogue, offering some of the most distinctive and satisfying dance we witnessed in the biennale.

Compagnie desprairies, site-specific performance, Là commence le ciel

photo Michel Cavalca

Compagnie desprairies, site-specific performance, Là commence le ciel

Lyon’s dance biennale was our first visit to a festival dedicated entirely to dance; such an event is a true rarity in Australia. It was an enlightening and enriching experience and it was wonderful that Australia’s Force Majeure could be part of it.

–

Biennale de la Danse 2006 Lyon, France, Sept 9-30

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 2-3