The evils of neo-liberalised warfare

Interview: Irving Gregory, Version 1.0, The Vehicle Failed To Stop

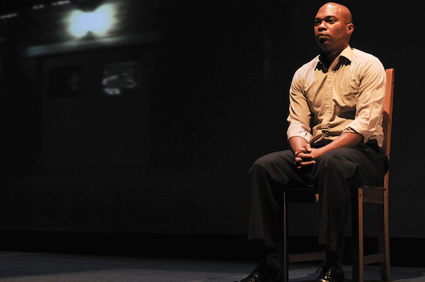

Irving Gregory, The Disappearances Project

photo Heidrun Löhr

Irving Gregory, The Disappearances Project

After several years of ‘emergence,’ version 1.0 erupted into prominence at Performance Space in 2001 with The second Last Supper featuring a mix of the not-so ‘old guard’ from the contemporary performance community and the new, along with nightly consumption throughout the season of an enormous volume of red wine in an outrageously surreal, promiscuously wide-ranging taboo-busting epic.

Moving resolutely on to tackle political issues still largely unaddressed by Australian theatre, version 1.0 has rarely lost that sense of fun, even when tackling the darkest of subjects. Material taken from public and parliamentary records about the Children Overboard saga (CMI, A Certain Maritime Incident, 2004), Government media manipulation about the Iraq War (The Wages of Spin, 2005), Australian Wheat Board corruption in Iraq (Deeply Offensive and Utterly Untrue, 2007) and local government corruption (The Table of Knowledge, 2011-12) has been ironically reframed, physically, vocally, spatially and technologically, without resorting to satire or mimicry.

These works are still enormously relevant. Version 1.0 has also tackled masculine violence, the suffering of people whose relatives have disappeared—in The Disappearances Project—and “place, tourism and atrocity” in Kym Vercoe’s seven kilometres north-east (which has become a film, Jasmila Zbanic’s For Those Who Can Tell No Tales, featured in the 2013 Toronto Film Festival), and a history of the maltreatment of the people of Palm Island, Beautiful One Day, produced as a collaboration with Ilbijerri Theatre. For Canberra 100 the company recently created the much praised The Major Minor Party, about the ACT-based Australian Sex Party and its impact on Australian political culture.

Hot on the heels of The Major Minor Party comes The Vehicle Failed to Stop. In 2007, a 49-year-old taxi-driver Marou Awanis and her friend Jeneva Jalal were shot by private security contractors working for the Australian-owned company Unity Resources Group, “an integrated risk mitigation solutions provider for clients in complex, challenging and fragile environments, globally headquartered in Dubai.” Apparently the car got too close to a security vehicle albeit in a safe part of Baghdad. Coming after similar deaths, the killings resulted in widespread protest. The Iraqi Government attempted to ban the American security firm Blackwater from the country. A legal team working on behalf of the women’s families filed a suit in Washington. However, the American Government claimed to bear no responsibility for overseeing outsourced security operations, therefore the families have had to sue URG. RT spoke with Irving Gregory, a current member of version 1.0, about himself as a performer and the issues focused on in The Vehicle Failed to Stop.

Tell us a little bit about your background as a performer.

Basically I came out of New York University’s Experimental Theatre Wing in the Tisch School of the Arts undergraduate drama program. Very lucky there to have worked with people like Anne Bogart among other people in the mid-80s before she came up with her Viewpoints concept. I worked the downtown dance and performance scene in New York in the 80s. Then I travelled to Germany, worked in the free scene in Munich and other cities. Travelled around there. Came back to the States in the 90s, tried to do movies for a while and got back into theatre in the late 90s when I joined the Collective Unconscious in New York.

While at the Collective Unconscious—which we ran as a collective and put shows on there to pay the rent basically—we developed a performance called Charlie Victor Romeo which won two Drama Desk Awards, travelled all over the US, was co-produced in Japan, came here to the Perth International Arts Festival, was filmed by the Air Force for training, picked up by the medical community…It had a long and storied history and was made into a film last year, which premiered at Sundance Film Festival this year.

The text is the transcripts of six actual airline emergencies—black box transcripts which we dramatised, live onstage with an award-winning sound design. In 2004 Time magazine named it as one of the best plays of the year. I’m in the film and also credited as one of the screenwriters as I’m one of the creators of the play.

What drew you to Australia?

Well, I got married. I met my wife in Perth when I was here in 2002. We stayed in touch and got married in 2008. I then talked to people at version 1.0. They got back to me in 2011 for The Disappearances Project. That’s when I joined the company.

What’s the attraction of working with version 1.0?

Well it’s always the people and the work. From Charlie Victor Romeo, I had an interest in this type of theatre—theatre documentary style and/or verbatim style. I’d done elements of that kind of work since the late 80s actually. I did a piece with [performer, dancer, painter] Fred Holland, basically as a sound operator. He had an interview in the piece, which was about the fight career of Jack Johnson, the great boxer, and the interview with him was about when he had to surrender the title—because the Feds were going to prosecute him under the Mann Act [a law against ‘white slavery’ but used to criminalise consensual sexual behaviour between blacks and whites. EDs]. I worked with this piece to re-integrate it a bit more and discovered the power of an interview—real words—and how that can work dramatically. I worked subsequently in Germany with an interview-based piece called Packing and Shipping. Learning version 1.0 did that kind of work I became interested in them. The Disappearances Project was the first work I did with the company and The Major Minor Party, which we premiered in June, is the second.

The Vehicle Failed to Stop, is predicated on a terrible incident in Iraq, when two women were killed by security contractors.

The initial development at the Sydney Theatre Company in 2012 was by David Williams, Kym Vercoe and Jane Phegan. I worked on the development of the idea in March of this year. In working with verbatim and/or interview and/or transcriptional sources there’s a lot of editing that has to be done, a lot of focus on what is important and what needs to be conveyed. What we brought out in this latest development was not only the fact that extra-judicial killing had occurred in an environment where a lot of this kind of thing had taken place through the use of contractors, but a focus on the whole nature of privatisation. And this extended to the entire administration of Iraq during and after the invasion. Paul Bremer [Administrator of the Coalition Provisional Authority of Iraq after the 2003 invasion], through one of his notorious orders, basically opened up the country to exploitation by any and all private industry because that was a part of the strategy.

Based on the neo-liberal assumption that this would solve everything.

Exactly, but then you have it taken to the extreme, being imposed upon an entire country at one time. It’s about the broadest sort of utilisation of that economic theory possible. You invade a country, you knock out the government, you fire everyone and you just say, ‘well, it’s open season for any and all entrepreneurial ideas to come in here internationally with no accountability to anyone.’ What are the consequences of this? One we found directly related to the incident with the two women is that you have a lot of security people on the roads operating beyond anyone’s law with the only consequence of their actions that they may be fired and sent out of the country. There’s no jurisdiction.

What kind of verbatim material are you using?

Documents derived from books and articles about Erik Prince, the head of Blackwater Security Consulting, and about the case itself as it was attempted to be adjudicated in the US and abroad. Then there are the pronouncements of and articles about the Bremer administration and also transcribed documentary footage about other elements of the privatisation and the experience of private contractors in Iraq. Another thing is that these companies—Halliburton, Kellogg Brown & Root, Blackwater, which reaped billions of dollars in profits, out of this wide-open, almost Wild West, boomtown environment—were not necessarily protective of their employees. They just send them to a country that has been supposedly ‘secured’ and what happens is people who aren’t security contractors, but truck drivers, are killed. Because the companies want to maximise profits, because they have a bottom line to meet, these men find themselves being shot at in gasoline trucks. What is that?

One of the companies involved is the ex-military Australian-owned URG.

Yes, they were the contractors involved in the incident with the two women being killed. In Afghanistan right now there are more contractors than troops. People may not know that. Of course, when the troops leave next year there’ll be opportunities for private contractors to continue security and other sorts of missions there. So this is a new element of international relations—how governments deal with international crisis points. Because when you don’t have to use your national army, when you can use private companies, then you’re not really accountable to anyone.

It goes nicely in tandem with the roboticisation of war in the form of drones and so on.

Well, it’s the 21st century we’re looking at. This is the way things are going, the way that war is now being prosecuted, or small wars—that’s all we have any more, isn’t it?—a changing environment in modern conflict, an environment without accountability or responsibility.

Carriageworks, version 1.0, The Vehicle Failed to Stop, Carriageworks, Sydney, 15-26 Oct

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. 35