The good book: ADT at 50

I read Adelaide writer and academic Maggie Tonkin’s Fifty, Half a Century of Australian Dance Theatre, in two shifts, thoroughly engaged by the ease of its informal account of the history of the country’s longest-lived (if frequently against the odds) contemporary dance company and the best known internationally. Tonkin makes no claim for the book as a formal history; it’s essentially an aesthetic response with, she writes, “a focus exclusively on the artistic achievements of the ADT and its many works.” Fifty admirably tracks artistic influences, lineages and legacies. Works are briskly evoked, ample large photographs are provided and reviews cited, but, where apt, ticket sales, deficits, funding ups and downs and sponsorships are also invaluably noted, pointing the way for future researchers and enriching our sense of the practical complexities involved in art-making.

A special part of Fifty’s appeal for me is that ADT formed when I was in my early 20s. I witnessed not a few works from the late 1960s until 1986 when I left Adelaide, and have seen subsequent works since when (too rarely) toured or I returned for festivals. Fifty conjures a living history.

Although emphatically not “a settling of old scores,” Fifty does not stint on recounting the effective dismissals of four artistic directors by successive boards and detailing the eventual constitutional reform that had to be implemented by the time Garry Stewart became Artistic Director and a member of the company’s board. What Tonkin doesn’t mention is that similar problems were experienced by a swathe of South Australian arts organisations and companies across these 50 years, but that would require a deeper cultural and political reading beyond this book’s remit. The pain felt by those four ADT artistic directors still palpably lingers on the pages of this largely interview-based book.

Tonkin’s consistent approach to her material throws up striking continuities in ADT’s history from directors with very different visions. Multimedia and cross-artform collaborations are there from the beginning, dance as ‘theatre’ (though rarely as narrative) is variously and vigorously realised, ballet classes persist throughout and non-dance body regimes (from Alexander Technique to yoga, martial arts and also meditation) are successively introduced. Overseas choreographic influences are marked but Australian makers, many now prominent, are persistently nurtured. Touring is frequent, with bouts of enormous overseas success. Big collaborations in theatre, opera and spectacle reach wider audiences. Classes and community projects flower from time to time.

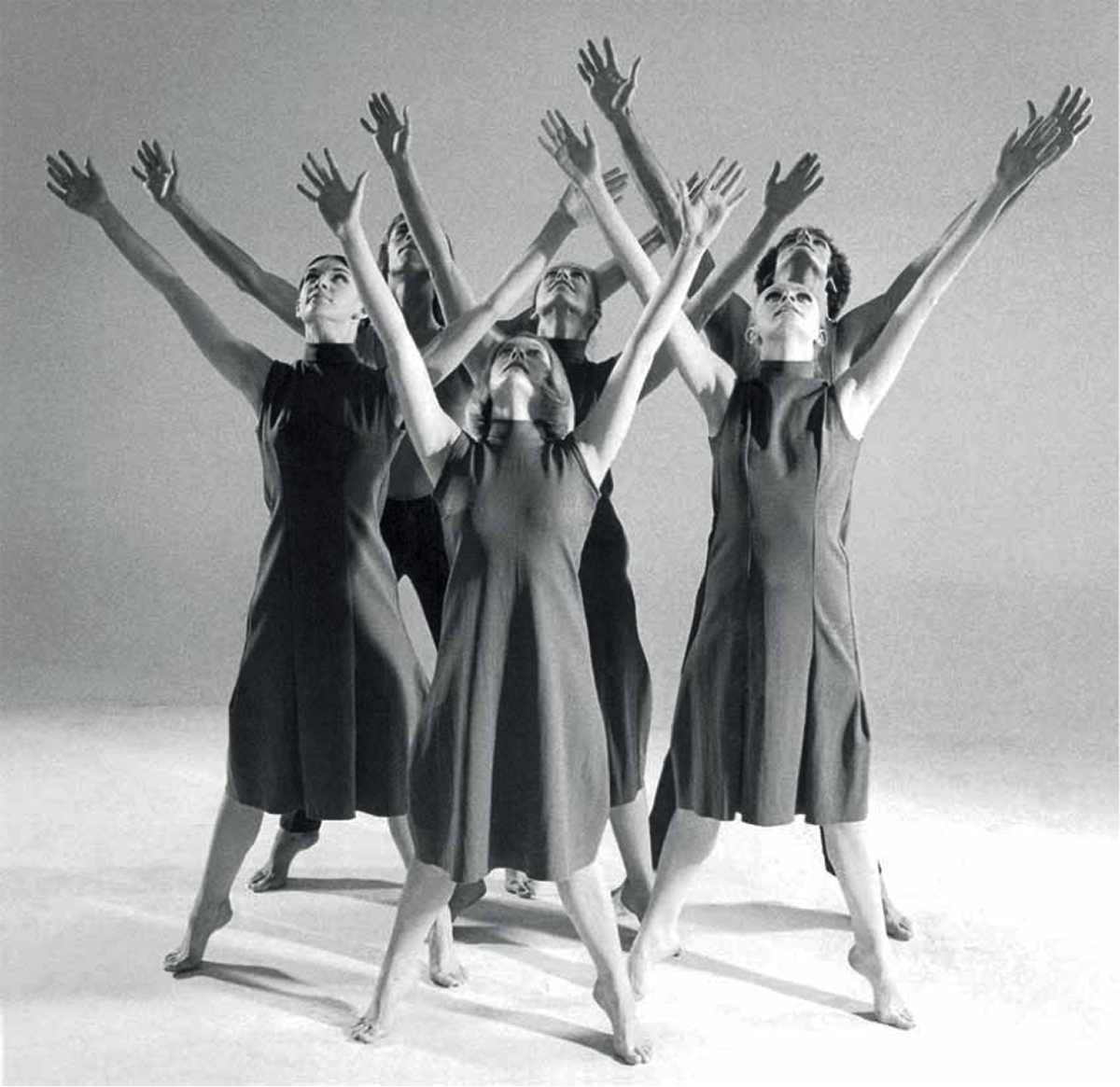

This Train, 1970, choreographer Elizabeth Cameron Dalman, photo Jan Dalman

Taking shape

How much of ADT’s history can be read in its beginnings? Founder Elizabeth Cameron Dalman provides her own account of her artistic directorship, emphasising a then rare commitment to Australian dancers and choreographers, composers, visual artists and the projection and computer art of Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski (see Stephen Jones’ Synthetics, MIT, 2011) in seminal multimedia productions. Social issues, the Australian landscape and Aboriginal culture preoccupied Cameron Dalman, as did Asia, where the company first toured. In naming the company, she writes, two words were critical, Australian and theatre: “We believed that by using the word theatre it would allow us to push the boundaries of dance performance and lead us into new fields of movement and dramatic experimentations. It also connected us strongly to artists of other disciplines who were breaking new ground in their art forms.”

Cameron Dalman was particularly influenced by José Limón whose work she’d seen in London in 1957 and especially the Colombian choreographer Eleo Pomare whom she worked with in Holland and brought to Australia and whose work astonished us with its vivid theatricality in the 1972 Adelaide Festival. The company toured successfully, gained Australia Council funding but at the cost of having board members selected by the Council. After a final performance in a late 1975 Sydney season, Cameron Dalman and the performers found letters in their dressing rooms announcing, with five days’ notice, her dismissal and the dancers’ contracts terminated. As with subsequent sackings we’re not made privy to the board’s motivation.

A new ADT

Two years later in 1977, English choreographer Jonathan Taylor, ex-Ballet Rambert, launched a new ADT with new dancers and a strong UK choreographic input which would include Glen Tetley and Christopher Bruce as well as US guests but also, as Cameron Dalman had done, nurturing Australian talent from within and outside the company, including Graeme Watson, Jacqui Carroll, Barry Moreland and Ian Spink. Tonkin details the company’s output, which in the English repertory manner, was prodigious, with the company servicing both Adelaide and Melbourne (thanks to joint states funding), touring here and overseas (opening the Edinburgh Festival in 1980; eight-week European tour in 1982) running workshops and an influential children’s project, appearing on live TV broadcasts in Australia and Europe and making films. As with Cameron Dalman there was a sense of engagement with the zeitgest: sexual politics, punk and contemporary classical Australian music and, in collaborations with event wunderkind Nigel Triffit, spectacle. Wildstar (1979), based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead, ran for two and half hours, the company reaching out with it to a receptive, wider audience here and overseas.

Whatever the reasons for Taylor’s effective removal, doubtless drops in funding levels, limited box office in a small city and Victoria pulling out of joint funding (a merger with Sydney Dance Company was then mooted) were all contributing factors despite the company’s critical and touring successes. It’s fascinatingly revealed that when Taylor’s contract was not renewed, the company lost its repertoire — Taylor owned his works and overseas ones were licensed to be directed by him.

Controversial caretaking

A caretaker period ensued in 1985 overseen by 1986 Adelaide Festival Artistic Director Anthony Steel and a former Nederlands Dans Theater dancer and rehearsal director for Jonathan Taylor, Lenny Westerdijk, once again revealing the company’s persistently adventurous spirit. Their program included Nigel Kellaway’s controversial Fantastic Toys, to a score by Sarah de Jong, and for the festival, A Descent into the Maelstrom, a large-scale collaboration between American choreographer Molissa Fenley, the Phillip Glass Ensemble and ADT with a notable set design by Eamon D’Arcy. Debate about these works “heated up the critical climate.”

Tu Tu Wah, 1991, choreographer Leigh Warren, photo Jeff Busby

Pedagogy & postmodernities

Leigh Warren, who’d spent six years with the Nederlands Dans Theater and is a choreographer whose pedagogy is always spoken of highly by Australian dancers, became the next artistic director. In one of many moments in the book with an ironic edge, Tonkin notes that of the previous company of dancers Warren did not ask Garry Stewart to stay on: “experience told him that the training regime [Stewart] would bring to the company would not work for him or his physicality.” For choreographers, Warren brought in Graeme Watson, New Zealand’s Douglas Wright and Nanette Hassall to make new works, including in 1987 the latter’s Open Weave to a live score by Robert Lloyd and a design by Mary Moore of horizontal poles ‘dancing’ above the performers. Other choreographers who were commissioned included Helen Herbertson, Michael Whaites, Sue Peacock and Kate Champion.

The challenges of postmodern dance for the performers compelled Warren, writes Tonkin, to institute “formal composition classes based on those he had taken at Julliard.” José Limón was once again a key influence, but also William Forsythe. As in all phases of ADT’s history to the present, classical ballet training continued to provide precision and strength, this time alongside Alexander Technique.

In another recurrent trend, the company successfully expanded its reach in collaborations with the State Theatre Company in Cabaret in 1991 and with Opera South Australia in Gale Edwards’ production of Nixon in China in 1992. Not long after, and despite a tour to Asia and the first Australian premiere of a work by William Forsythe, Warren’s contract was shortened as the board determined to go in a new direction. Warren poignantly reflects on his standing as a choreographer at the end of his tenure: “I often ended up making work to balance the program around the guest choreographers, so nothing would impede their absolute freedom to make whatever work they wanted. I made more conservative work to counterbalance their experimentation, and as a result, I was criticised for creating works that were too middle of the road.” This is an underestimation of Warren’s best work.

Choreographer as director/collaborator

After another caretaker period led by Bill Pengelly and with a touch of rebranding the company became Meryl Tankard’s Australian Dance Theatre and with the choreographer who had performed for six years with Pina Bausch, often in key roles, came an approach to collaborating with dancers, and actors in her company, that was “more democratic and inclusive,” something, says Tankard, that emerged from working with student actors at NIDA. As subsequently with Garry Stewart, the choreographer becomes director and co-collaborator with her performers, even though the latter often didn’t know the overall direction she was taking them. Dancer Tuula Roppola is quoted as saying, “[Meryl] always treated us as creative artists. We were never just doing steps or movement; we were always working with intention behind the movement.”

As well as hugely successful productions like Furioso that travelled the world with its striking aerial work and physical intimacy, and, with partner, photographer Regis Lansac, generating multimedia performances and working innovatively with live music, Tankard and ADT also collaborated extensively with Opera Australia on Gluck’s Orphee et Eurydice. There was an Australian Ballet commission, Deep End, for Tankard, the company won critical praise and numerous awards and toured globally. But the end was nigh. Tonkin writes, “paradoxically, it was this heightened international profile … that would be held against her.” Even though Tonkin details at some length the likely motives for the sacking (just after the success of Possessed at the 1998 Adelaide Festival) and subsequent events (in the press, in parliament), it remains difficult to all but guess what actually happened, especially given that Tankard was legally silenced. What ensues is remarkable — a mooted proposal for the Australian Ballet’s Artistic Director Ross Stretton to take over (Dalman and Tankard protested this likely destruction of ADT’s heritage), while retaining his AB position, or for the company to merge with the financially troubled WA ballet. Neither happened, but what kind of company did the board imagine was their cultural responsibility?

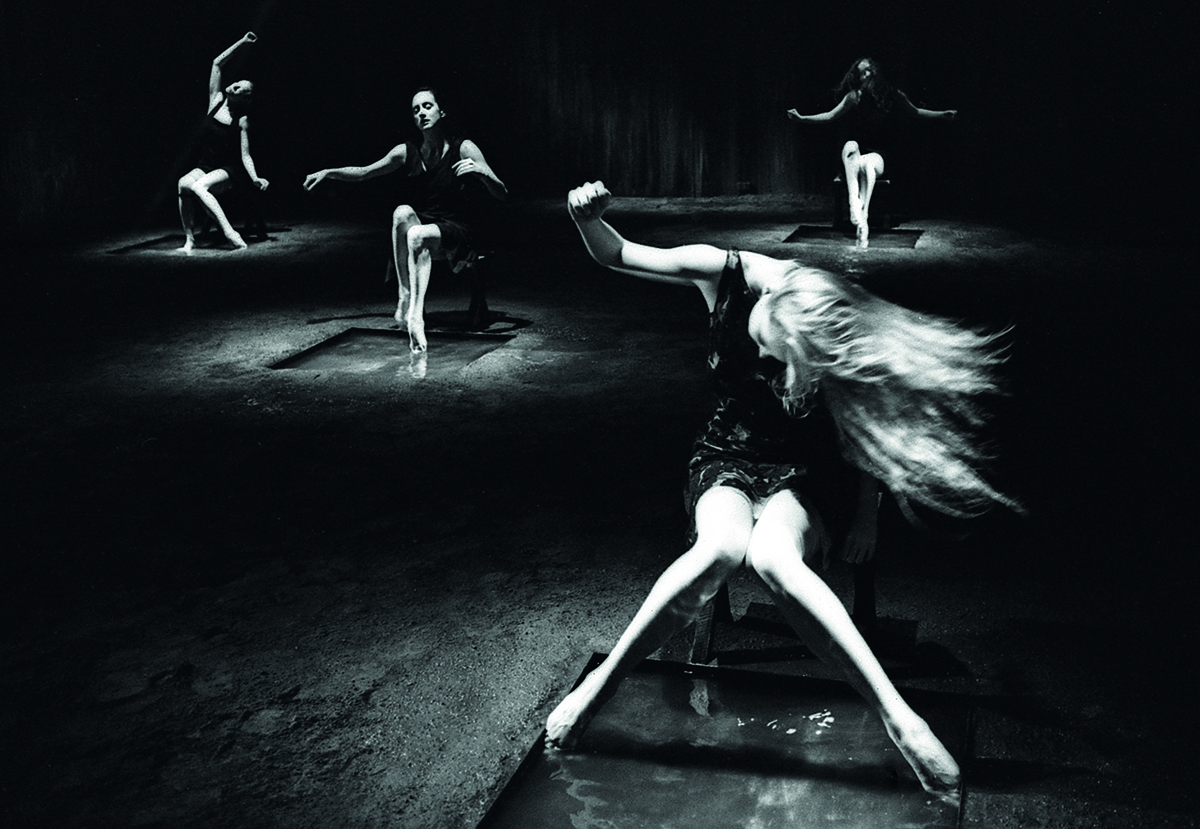

Songs with Mara, 1993, ADT, photo Regis Lansac

A new body of dance

Garry Stewart’s tenure has seen a heightened multidisciplinarity and the implementation of extensive and intensive skills training that had made Leigh Warren wary. These became integral to ADT’s practice. Stewart tells Tonkin, “As we toured, the vocabulary became seamless in the way in which entrained technique does. It transcended into a domain I wasn’t expecting, ending up saturating [the dancers’] bodies and becoming a consummative cohesive vocab rather than a series of skills.” One result was that distinctive moves were named after the dancers who “pioneered” them, for example, a Flying Craig after Craig Bary. As with Tankard, Stewart collaborates intensively with his performers, crediting them as co-choreographers.

It was Stewart’s Birdbrain that initially made the ADT internationally prominent, starting out in Galway in Ireland, where a nervous Stewart walking the streets, assumed failure, and then on to Seoul and later Sydney, Toronto, New York and Ottowa. Why did ADT succeed in Europe at a time when choreographers — Jerome Bel, Xavier Le Roy — were stripping dance of virtuosity and speed, “critiqu[ing] the notion of dance’s attachment to constant kinesis.” Stewart says, “At that time my work claimed an oppositional space with its hyper-virtuosity that, however, seemed to capture the audience’s imagination,” adding, that to have “Derrida, Swan Lake and breakdance and very contemporary — almost pop video — graphics and semiotics and virtuosity altogether in the same sentence was an unusual amalgam. With Birdbrain we seemed to crash through the domain of postmodernist minimalism with a certain naive bravura, I guess.” Stewart attracted major overseas commissioning partners and, once certain of his work, reached out to international arts collaborators in photography, robotics, video engineering and design, giving ADT a cosmopolitan edge underlined by the intellectual and scientific scenarios that Stewart gives life to in his works.

Stewart has enjoyed huge success and, compared with his predecessors, stability and certainty. His Ignition program breeds new choreographers, there’s an ADT youth ensemble, diversification has yielded installations, films and new community projects and the ambition to create an international choreographic centre. But as Tonkin reports, it’s never easy: “extensive international touring is the only way ADT can stay within budget because it generates a fee without box office risk, whereas touring within Australia is made prohibitively expensive without special funding.” Local box office is small, interstate venues are cautious. Consequently, ADT’s international reputation exceeds its national one. But the company serves Australia superbly and Adelaide in particular where Stewart and the ADT are so clearly building a dance culture on and beyond the stage, as in its Embedded program of dance in public spaces, recalling in spirit performances by Elizabeth Cameron Dalman’s ADT nearly 50 years ago and giving cogency to the stirring book that is Maggie Tonkin’s Fifty.

Fifty is another welcome addition to Wakefield Press’s list of finely designed and produced dance books — Alan Brissenden and Keith Glennon’s Australia Dances, Creating Australian Dance 1945-1965, Erin Brannigan and Virginia Baxter’s Bodies of Thought, 12 Australian Choreographers (co-published with RealTime), Alex Makeyev’s Captured, Leigh Warren and Dancers, and The Ballets Russes in Australia and Beyond, edited by Mark Carroll. In a country with limited, let alone accessible, documentation of the performing arts, Fifty is an important addition to the record.

Although focusing principally on ADT’s artistic achievements, Maggie Tonkin skilfully, consistently and accessibly contextualises them in terms of the unpredictable financial and political forces that always threaten to keep art in check. Some things go unmentioned, such as the competition at times for funds between ADT and Leigh Warren and Dancers in a small city with a limited arts budget — and most of the reviews cited are apt for a celebration but reveal little of Adelaide’s critical dark side. Fifty’s recounting of the effectual sackings of four artistic directors, however, is chillingly inescapable, texturing the joys of success and visionary self-belief with harsh realities. But what stands out in the end is ADT’s prodigious productivity, so many productions, so many commissions, so many wonderful works and dancers (from Jennifer Barry and Cheryl Stock to Antony Hamilton, Larissa McGowan and Kimball Wong and all listed in the excellent addenda). Words and images convey the passing of generations and the emergence of careers and above all the durability of Elizabeth Cameron Dalman’s vision. Every few pages, I would pause, to recall a work or wish to see one never experienced. It’s that kind of book.

–

Maggie Tonkin, Fifty, Half a Century of Australian Dance Theatre, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2017, RRP $75.00

Top image credit: Furioso, 1993, ADT, photo Regis Lansac