The interrogatory path

Oliver Downes: interview with Anthony Pateras, tetema, Geocidal

Drums pound in ceremonial commencement; a lone throat singer issues a deep incantatory note; a choir of male voices loom in warning, their mordant harmony blending with a metallic wash of strings, the sound rent by a wailing clarinet; a savage muttering appears, half-formed echolalia cut with madness; the texture rises to a peak, a voice calling out in almost snarled lament, then suddenly cut off, leaving the buzz of a lone insect scuttering over the deep hum of industrial machinery. Then all hell breaks loose.

Drums pound in ceremonial commencement; a lone throat singer issues a deep incantatory note; a choir of male voices loom in warning, their mordant harmony blending with a metallic wash of strings, the sound rent by a wailing clarinet; a savage muttering appears, half-formed echolalia cut with madness; the texture rises to a peak, a voice calling out in almost snarled lament, then suddenly cut off, leaving the buzz of a lone insect scuttering over the deep hum of industrial machinery. Then all hell breaks loose.

Thus opens Geocidal, the debut record of tētēma, a new collaboration between Australian composer, pianist and electronic wunderkind Anthony Pateras and maverick vocalist Mike Patton, demi-god of 1990s alternative rock outfits Faith No More and Mr Bungle, high-priest in the church of John Zorn and most recently dapper interpreter of 1950s-60s Italian pop. With Geocidal they have produced a densely visceral offering that endeavours to “create a sound world from scratch.”

The pair became acquainted after Pateras sent recordings of his grindcore duo PIVIXKI to Patton’s label, Ipecac. Something must have clicked, as Patton got in touch while touring Australia with experimental metalheads and miners of pop-culture Fantômas in 2009. “I’ve dealt with a lot less famous people who are all about food anecdotes and career monologues and it’s incredibly tedious,” says Pateras. “It was unnerving to us both how natural it [working together] felt. I really respected the fact that there was this guy who could basically just cruise on major label royalties if he wanted to, but instead chose a path of interrogation.”

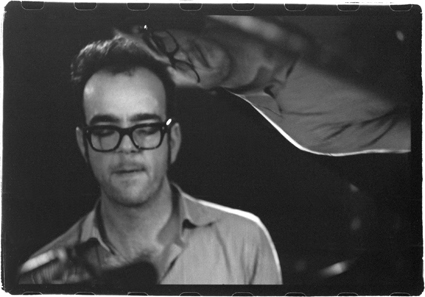

Anthony Pateras, live in Lille, 2014

photo Philo Lenglet

Anthony Pateras, live in Lille, 2014

A path most certainly shared by Pateras, whose extensive back catalogue of works for solo piano, small ensembles, percussion and electronics regularly pushes into the underexplored sonic terrain that lies between notation, improvisation and electronic programming. Moreover, he cleaves boundaries between the ‘culturally sanctioned’ sphere of traditional composition, offering commissioned works such as most recently A Reality In Which Everything Is Substitution (2014) for solo amplified flutes and electronics or the forty-minute piano solo Blood Stretched Out (2014), while also pursuing more avant-garde projects such as PIVIXKI or Kayfabe, a glitch spattered collaboration of experimental electronica with Natasha Anderson. “Composition is amorphous across the board,” Pateras comments, “all of your experiences in playing, listening and reading feed into everything you do. It’s counterproductive to distinguish.”

From the ritualistic opening of “Invocation Of The Swarm,” Geocidal chews its way through an at times unsettling and often vicious exploration of rhythm and timbre. Patton, who absorbed Pateras’ musical tracks over a year before contributing vocals, uses his extraordinarily versatile voice as much for atmospheric or textural effect as for delivering lyrics. A song such as the seven and a half minute centrepiece “Ten Years Tricked” contains sections of eerie quasi-Gregorian chorus but also deep droning, spitting, gurgling, girlish sighs, imaginary words and other timbral effects. Other songs such as “Irundi” or “Tenz” are built around pulsating rhythms, Pateras’ orchestration providing touches of colour in framing Patton’s voice. “When I was doing this, ostensibly writing songs, which normally prioritise pitch and form, I was coming at it from a different angle,” says Pateras. “Maybe to some people it’s danceable, but to me it was about creating something physical—not in the macho noise sense of the word, nor the superficial-buzz-word ‘psychoacoustic’ sense—[but] trying to make something which reflects what I love about sound and which has a physical affect on me.”

An important undercurrent to this prioritisation of rhythm over other musical elements came about in his response to the ideas of French cultural theorist Paul Virilio, who argues that the accelerated development of technology has disrupted humanity’s natural rhythms. Pateras was particularly drawn to Virilio’s equation of the instanaeity that modern technology provides with human immobility and paralysis—“even when immobile we are in motion” chants Patton on “Tenz.” “Instead of accumulating skills, which takes time and focus, we just want to go fast,” explains Pateras. “I was very conscious of somehow magnifying rhythmic and timbral nuance in the music when I could…I wanted to de-quantise everything, deny instantaneity, create a space where going the long way around didn’t matter, because you find important ideas that way. The idea [that] you open your computer, pull up a few presets … it’s death, but that’s what gets taught as composition these days. We teach musicians how to die before they even start.”

Having developed the seed of the record over a couple of weeks staying in “a really shitty part of France—depressed rural community, lots of drunk soldiers, middle of nowhere,” Pateras enlisted drummer and percussionist Will Guthrie to assist in fleshing out the lacerating rhythms that propel many of the songs. “[We] riff[ed] on variations of the core ideas together, recording the drums and prepared piano simultaneously,” he explains. “I intentionally ran the session to generate the most flexible material possible—things which could be stitched together in unorthodox ways. Ultimately they were just rhythmic cells recorded for maximum elasticity.”

From there, the material was edited and wittled down, synthesisers added and parts written for the diverse array of instrumentalists, strings, clarinet, trumpet, percussion, acoustic guitar and recorders, whose contributions lend the record its dizzyingly multi-faceted texture. “I had the idea to…record every single element in the real world and manipulate/edit it electronically,” Pateras says, “encouraging [the musicians] to mimic or ornament the synth parts…so there’s always this hybrid electro-acoustic thing going on.” As he explains, this approach was informed by “[Morton] Feldman’s observation on what makes Xenakis’ music interesting: taking conventional instruments and bringing them into a world of hallucination, rather than using hallucinatory instrumentation, and bringing it into a world of convention. This record…was about canalising the tools I had to find a unique constellation.”

For a record so preoccupied with the collapse of boundaries – even the word “Geocidal” suggests the death or erasure of place—this concern grew less from any desire to make a broader political point, but emerged from a desire to explore both “the idea of the finisterre, or always being on the edge of known territory” as well as the practical circumstances from which the recording emerged. “I moved country twice while making this,” says Pateras, “I was constantly insecure and decentralised because I was in a permanent state of adjustment. And that is a really amazing place to make music in, because you have nothing but the material that’s coming out to guide you. I feel that’s what’s wrong with a lot of music—it becomes about filling a brief rather than simply using what you have at your disposal to see what happens.”

tētēma (Anthony Pateras & Mike Patton), Geocidal, Ipecac Records, IPC-167, http://ipecac.com/artists/tetema

See the full interview with Anthony Pateras.

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. web