the longing for healing

laetitia wilson: magnesium light; the world is everything that is the case

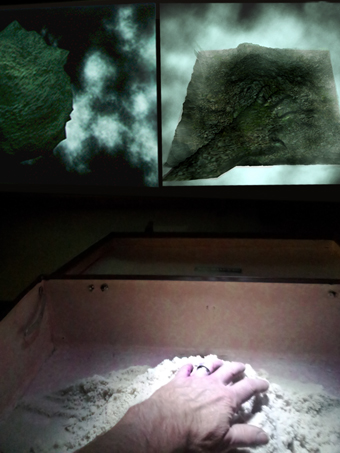

Dennis Del Favero, Todtnauberg, 2009, video still

courtesy of the artist

Dennis Del Favero, Todtnauberg, 2009, video still

MAGNESIUM LIGHT BURNS INTENSELY BRIGHT AND WHEN EXTINGUISHED LEAVES A TRACE, A DARK AFTER-IMAGE ON THE RETINA AS A GHOSTLY SPECTRE OF THE BRIGHTNESS THAT ONCE WAS. THE WORKS OF DENNIS DEL FAVERO HAVE THIS SAME PLAY OF INTENSITY AND SHADOW THAT MIRRORS THE USE OF REAL WORLD EVENTS PORTALLED INTO PARALLEL NARRATIVES OF FANTASY, DESIRE, LOSS AND DISORIENTATION.

Del Favero’s new show, Magnesium Light, comprises two video works, You and I and Todtnauberg. Each is anchored in a poignant historical moment but moves beyond its actuality to delve into more psychologically embedded folds of imagination and meaning.

Both video works spring from encounters between individuals. You and I is a sexual encounter. A female voice-over is heard over finely edited black and white frames of a passionately engaged heterosexual couple. The words could be those genuinely whispered in a love scene between equals, but instead the encounter resides in a realm of dark delusion, brutality and injustice. The woman is clearly the person in control and the context becomes apparent as the image cuts to a body in uniform and the piece closes with the woman as a military figure of authority wielding power over her lover who is now the ubiquitous icon of the hooded man of the Abu Ghraib torture images.

A remarkable thing about the images that came out of Abu Ghraib was the fact of seeing women in roles traditionally ascribed to men; committing war crimes at the extremes of perversity and debasement. It is not that women are incapable of such acts, but they are so rarely pictured as such. Then there is the additional consideration that somewhere, somehow, in their post-Iraq lives there must be psychological repercussions to their actions; that the memories insistently reverberate as part of the post-traumatic consequences of war. You and I could represent the character of Lynndie England, for example, finding a twisted way to cope with her actions, a way to counter those repeated images of her cheesy grin and thumbs up incongruously against scenes of utter human pathos. Her memories here become transformed into sexual fantasy and the suggestion is that this functions to obfuscate the horror of such realities.

Todtnauberg takes an encounter of a different kind, between two minds rather than bodies. The piece is dominated by two men walking through a high-hedged labyrinth, occasionally intersecting one another. The characters are French poet Paul Celan and philosopher Martin Heidegger. In actuality they crossed paths a number of times between 1951-70 and each was compelled by the other’s work, although the attraction was not uncomplicated. Celan was of Jewish descent with a family lost to the Holocaust and Heidegger a Nazi sympathiser. These differences came to a head in a particular encounter in 1967 when Celan journeyed to the Black Forest to visit Heidegger, to question him about his anti-Semitic views. Heidegger failed to appease Celan and Celan could not forgive him. Following the encounter Celan penned an impenetrable poem, also titled Todtnauberg, and not long after he drowned himself in the Seine.

Todtnauberg recreates the charged encounter, washing over the viewer in melancholy tones through the combination of smooth-panning along richly dark, pine tree-lined paths that lead nowhere and a whispery voiceover full of remembering, forgetting, questions, doubts and guilt. Dripping with restraint and unresolved dialogue, it communicates the longing for healing, the pain of silence and the fickleness of memory. Occasionally scenes from the war surface—soldiers marching, fires burning. This additional visual element seems an unnecessary literalisation of the content of the piece, just as the scene with the hooded figure makes obvious the pretext of You and I. These pointers could have been omitted without the works losing their strength.

Both works are aesthetically luscious and conceptually rich. Both deal with the unanticipated consequences of our choices and actions, our inability to come to terms with the past and that past bleeding into our present in a masked and obscurantist guise. Del Favero applies his signature technique of recreating a story out of a news event; the works extract an essence from the grand-scale, external, public account and inject it into stories of unspeakable, personal and private imaginaries.

Mark Cypher, Propositions 2.0

Running alongside Magnesium Light is The World is Everything that is the Case, co-curated by Paul Thomas, Vince Dziekan and Sean Cubitt and developed for ISEA2011 in Istanbul. This show hinges on the metaphor of the suitcase as a loaded symbol of mobility, migration and containment. A parallel association is formed with the realm of data and the routing of data packets through networks across the globe. Just as the contents of a suitcase are taken from our lives, fitted into a compressed space and then put back together once a destination is reached, so too are data packets in the ether disassembled and reassembled.

Several of the works use a physical suitcase and somehow combine it with a media artwork. For example, Tina Gonsalves displays the piece Chameleon on screens wedged in vertically poised cases. Faces fill the screens and are programmed to respond to user-presence. Unfortunately this piece falls prey to the sad fact of fallibility that too often haunts interactive work; the faces appear to suffer from some kind of multiple-personality disorder on a high-rotation stutter-loop. More seamless interaction is felt with the piece by Mark Cypher, Propositions 2.0. Cypher fills a prostrate case with sand and the sand-pit becomes a global playground with participant actions transferred to one projection and a knobbly spinning globe on an adjoining projection whose topology is the cumulative result of the manipulations of the sand. This work is aesthetically raw but conceptually engaging.

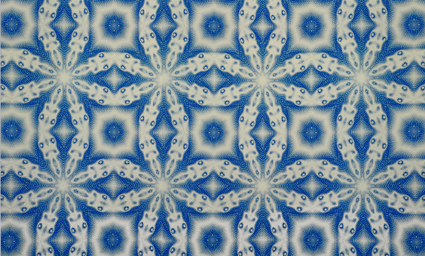

Karen Casey, Meditation Wall

courtesy the artist

Karen Casey, Meditation Wall

Arguably the most aesthetically mesmerising piece is Karen Casey’s Meditation Wall, a magnificent wash of colour and pattern. The pattern is made to resemble a Turkish mosaic combined with a desert bloom (Casey’s own paintings) with both Sufi and Aboriginal music making up the soundscape. The gridded kaleidoscopic morph is derived from data of Casey’s brainwaves in a state of meditation and it is debatable how much this impacts the resulting viewing pleasure; a pulsing mandala-like pattern is familiar to visual culture and seductive in and of itself. A background clang of breaking plates disrupts the soothing flow of Casey’s wall. The clang comes from Nigel Helyer’s sonic installation, Weeping Willow. As with the Meditation Wall this work eschews the literal inclusion of the suitcase and instead provides a layered and incisive commentary on cross-cultural dialogue and exchange between the Occident and the Orient through the symbol of the Willow Pattern dinner plate.

All in all something is amiss in the exhibition’s application of the metaphor of the old-fashioned suitcase and something is awkward about its resolution. Perhaps it is the inclusion of those antiquated suitcases at the entrance of the show, or the stretching of an entire show out of a Wittgenstenian notion that is never fully articulated in the works displayed. Or perhaps it is simply the fact that unlike a suitcase the show does not travel well and something is lost in its relocation to a global context distinct from its original formulation, for example the Turkish patterns no longer resonate with the world beyond the gallery walls. Nevertheless, as a whole, The World is Everything that is the Case is experientially diverse in its use of the icon of the suitcase and exploration of an evolving idea of virtuality in a transmigratory post-digital global phase.

Dennis del Favero, Magnesium Light; The World Is Everything That Is The Case; John Curtin Gallery, Curtin University, Perth, June 1-Aug 5

See Edward Scheer’s preview of Magnesium Light in RT109

RealTime issue #110 Aug-Sept 2012 pg. 54