The Mousoulis vision of independence

Jake Wilson

Michael Lee, The Mystical Rose

Ah, the Melbourne Underground Film Festival, where blather about Heidegger justifies the screening of yet more porn movies and Uncle Goddam: The Amazing Redneck Torture Tape. Cheap shots aside, at least one strand of this year’s MUFF exemplified Australian film culture at its very best. The Melbourne Independent Filmmakers Retrospective, assembled by Bill Mousoulis under the MUFF banner, was well-served by its programmer’s encyclopaedic local knowledge, as well as his incisive and catholic personal taste (though MUFF’s habitual gender skew remained intact).

The first session alone segued from quasi-narrative city symphony (Forgotten Loneliness, Chris Löfvén, 1965) to free-associating mock-essay (In Search of The Japanese, Solrun Hoaas, 1980), abstract lyric (Light Play, Dirk de Bruyn, 1984), hard-edged conceptual documentary (Someone Looks At Something, Philip Tyndall, 1986) and sledgehammer spoof (Dance of Death, Dennis Tupicoff, 1982). There were just as many surprises at a second miscellaneous session, focused on the 1990s and beyond: one highlight was Jason Turley’s Dirty Work (2003), a half-hour slice of unforced video realism about an outer-suburban teenager who receives a surprising offer from the couple next door.

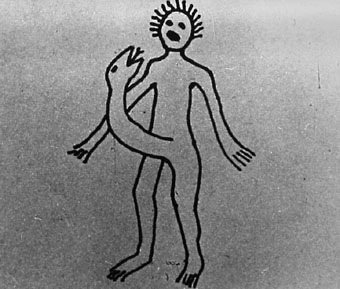

Watching these films, I began to suspect that for Mousoulis ‘independence’ is as much a spiritual category as a financial or formal one; this conviction was borne out in the 3 remaining sessions, each devoted to a single major filmmaker. Completed in 1976, Michael Lee’s Mystical Rose is unmistakably a document, both anguished and ecstatic, of ‘sexual liberation.’ The desire pent up by Catholicism breaks free in a barely controlled stream of images, as if the very principle of metaphor had been uncovered for the first time and seized upon as a key that might unlock the world. So stones become bread, or in an extraordinary sequence, a woman’s sexual organs are visualised as a steep and slippery mountain path. In his sensual re-envisioning of iconography—the Word made Flesh—Lee brings to mind Sergei Paradjanov, though his symbolism should be comparatively transparent to Australian viewers (when a man’s penis morphs into a serpent, which later becomes the infant Jesus, the meanings are startling but hardly esoteric). Marking Lee’s reconciliation with Christianity, A Contemplation of the Cross (1989) is less intense, but its images have the same bold immediacy, above all in the concluding vision of grace, with thousands of birds set free and flocking across the sky.

Chris Windmill, surely Australia’s most original comic filmmaker, is a visionary of a different order. Though comedy is often equated with playing to a crowd, Windmill plainly has no interest in trying to second-guess audience responses, or in anything that might impede his sober and absolute dedication to whimsy. Practical yet skittish women and good-looking, barely articulate young men abound in his universe, as do handwritten messages, ritualised housekeeping tasks, and maudlin surprise endings. In Mystery Love (1986), a woman falls in love with the Pope, who happens to live next door. Beards of Evil (1984) has a hero who winds up flying away on a pile of suitcases, but crash-lands and is sent to Hell, which turns out to be below St Kilda Beach. Later works are more opaque and have fewer identifiable gags, raising their daggy absurdity to a pitch that’s practically metaphysical, as in The Birds Do a Magnificent Tune (1996), the chronicle of an intimate relationship centred on ironing and Perry Mason re-runs, and his magnum opus to date.

John Cumming, in some ways the most sophisticated of these filmmakers, is also the hardest to characterise. Ranging from industrial Gothic (Obsession, 1985) to trippy allegory (Recognition, 1986), to observational satire (Sabotage, 1987), his films have few common denominators beyond their virtuosic editing and sound design, and their drive to undermine any single consistent reality, offering the fractured impression of a story rather than the story itself. As this suggests, Cumming is unusually aware of the political underpinnings of form; his comments at a subsequent question-and-answer session implicitly showed up the limits of current debates about the state of local filmmaking, which tend to focus unthinkingly on narrative aspects even when success isn’t crudely equated with profit. Indeed, now that avant-garde purism is dead, terms like ‘underground’ and ‘independent’ may have an unnecessary marginalising effect. Lee, Windmill, Cumming and others whose work screened at this retrospective deserve to rank high on any list of notable Australian filmmakers. And in the absence of independence—at least of a spiritual kind—is it really possible for art to exist at all?

Melbourne Independent Filmmakers: A Retrospective; curator Bill Mousoulis; The 5th Melbourne Underground Film Festival; July 8-18

RealTime issue #63 Oct-Nov 2004 pg. 19