the new academicism

adam geczy on the rise of the visual artist autodidact

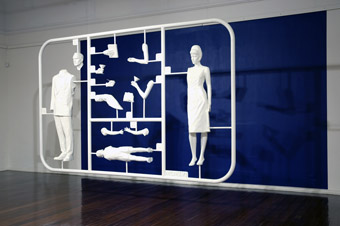

From HATCHED 07 National Graduate Show exhibited April 20-June 24, PICA. Guy Marc Bottroff (Adelaide Centre for the Arts, TAFE SA), A Model Family

photo Eva Fernandez

From HATCHED 07 National Graduate Show exhibited April 20-June 24, PICA. Guy Marc Bottroff (Adelaide Centre for the Arts, TAFE SA), A Model Family

THE TITLE OF THIS ARTICLE IS PURPOSELY MISLEADING. IT IMPLIES A NEOCONSERVATIVE AFFIRMATION OF DOGMA ENFORCED BY THE POWER OF THE ACADEMY. IT SUGGESTS RE-IDENTIFICATION WITH A CULTURE THAT IS SIMPLISTICALLY DIVIDED BETWEEN THOSE WHO subCRIBE TO ITS ETHOS AND THOSE WHO, BY VIRTUE OF THEIR OPINION, CREED OR STATUS, DO NOT. ONE OF THE UNFORTUNATE BY-PRODUCTS OF POLITICAL CONSERVATISM, AND ESPECIALLY ONE THAT HAS HAD PLENTY OF TIME TO ENTRENCH ITSELF, IS A SOCIAL CLIMATE THAT FORCES ITS LINES OF RESISTANCE INTO A STATE OF REACTIONARY DEFENSIVENESS THAT IT NEVER WISHED FOR.

The slow but inexorable transformation of students into clients, and the ever-elaborate chain of accountability have made tertiary institutions into service-based institutions in which abstract knowledge is supposed to fit assessable quanta and is continually the subject of suspicion or, worse, veiled contempt. It is a process that has made many tertiary teachers feel they are bound to retreat into a position of guardianship for areas of knowledge that they are in an increasingly diminished position to defend.

the digital transition

Let me be clear from the start: I am not shaking my fist at the ignorance of the young like some Dickensian curmudgeon. It is true that every age, deludedly or no, feels that it is the one that it is in decline, and that changing values are needlessly usurping the status quo; it is true that every age looks nostalgically on the past. With this in mind, we might also step outside this perennial reflex and look at the way people’s responses, expectations and areas of interest have altered since, say, the mid-90s, the rough marker for the entry of the internet into the domestic sphere and its adoption as both official and ad hoc tool for child education. Having begun my teaching career roughly during this change-over from the more analogue to the digital culture, I can see a change whose effects are more marked than ever in the last three to five years, that is, with the entry into tertiary education of students whose entire secondary education has been affected by internet culture in some way, whether glancingly or dominant. And I have come to the following conclusion, which I share with many of my peers: that digital mass culture is questionable on its own, but with guidance, with the appropriate educational frameworks, its benefits are astonishing.

Yet we are living in an intellectual climate whose powers to effect the right changes, within humanities and art education at least, are desultory at best. More and more students have been made to turn to their own resources, not as a result of lazy teachers, but because of less available quality time for education which is in turn caused by a weakening regard for what art and the humanities represent.

<img src="http://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/12/1265_geczy_visartsmorris.jpg" alt="From HATCHED 07 National Graduate Show exhibited April 20-June 24, PICA.

Sophie Morris (Curtin University of Technology), Memory (detail from installation)”>

From HATCHED 07 National Graduate Show exhibited April 20-June 24, PICA.

Sophie Morris (Curtin University of Technology), Memory (detail from installation)

absent online

What we have is an educational sector within Australia, and, it seems, also in the rest of the Anglophone world, that is gravitating to internet and non-contact teaching solutions—on-line delivery is the official term—faster than they have to assess the pedagogical implications of such changes. The result has been slowly to erode, diminish and undermine, through a kind of institutional stealth, courses whose outcomes are resistant to digital streamlining, and whose outcomes are unquantifiable. I am sure, for example, the decision by the University of Western Sydney no longer to take visual arts students is not based on campus logistics alone. (Departments and faculties have to pay a kind of levy based on the space they take up, hence courses requiring greater infrastructure lose out, the virtual, needless to say, wins.)

The kinds of pressures that the emphasis on tangible outcomes-based education exerts on students and staff of art schools continues to be the subject of hot debate. Will face-to-face teaching soon be something of the past? Teaching positions are frequently not replaced (the once pre-eminent Power Institute of Art History and Theory at Sydney University has lost at least two staff whose postgraduates have migrated elsewhere) and elsewhere staff-student ratios are subject to a level of pernickety scrutiny that defies common sense. Numerical analysis tends to win out in a field in which, strictly speaking, it has no real role.

suspensions of disbelief

When academics are under pressure, the students seldom rally to their cause. Nor should they. Universities are healthy places of dissent. The paradox that underrides a good humanities education is that students are taught within a vastly institutionalized structure about institutions and how to undermine them, since it is only through the constant redistribution of ideas that the institution can keep any vestige of life. But this tenuous balance within universities is shaken whenever the probity of the academics is called into account in a general and ideological way, that is, not on the basis of their own discipline as a direct and rigorous confrontation with ideas, but as a reactionary stymieing. When the abstract notions for which they stand are not valued, then many students are less inclined to listen, and, to return to my opening point, academics are made to stand with their backs to the wall.

For indeed a fundamental vector of humanities teaching is faith; suspension of disbelief. At a certain point, students are expected to believe that one idea is more valid than another; that this artist, writer or other exponent is better than that. This is not to advocate some false obeisance on the part of those who learn, rather it warns that when education enters into endless, turgid justification of its terms of reference, when taken to an extreme, it always winds up in a black hole. When it confronts a culture of mass skepticism, then the opposition between ‘those who know’ and ‘those who learn’ is pronounced to the point of conflict. Both blame the other, but the source of the problem is in an institution that doesn’t respect itself, or at least is no longer willing to respect the discipline as a valid point of inquiry, as something worth pursuing. When we try to excel in something that is undervalued at the outset, a large amount of energy is spent on legitimation. One has to do this enough as an artist within Australia without having to do it doubly in the institutions where knowledge is supposedly gathered and nurtured.

art only for art’s sake

The issue here is not to voice some Medieval law that students must obey their professorial masters, it is to say that there needs to be a certain protocol of accepting certain base strata so that students will be in a better position to confront their elders, previous generation, call it what you like. This is the dialectical process upon which art and the humanities is built. But what I think is currently emerging is a culture of dissent amongst students who seek to confront something but they know not what. And so they find themselves inexorably making art for the sake of making art. Education is what supplies the tools and the direction for the best kind of intellectual shifts and purges to take place. It is a matter again of the old chestnut of a rebel without a cause, but the condition is made considerably more acute by the information superhighway that throws all kinds of causes and concerns in its ‘user’s’ path.

Another way of saying this is that the internet has given birth to a new kind of autodidact. The core quality of autodidacticism, which makes it both charming and deadly, is that while it excels at absorbing information it has a limited ability to order or distinguish between one element and another. The internet has amplified this condition to an untold degree. Its users have more information at their fingertips than ever with an ever smaller capacity to discriminate. Sites like rotten.com make us laughing spectators of tragedy and deformity, and if humanity is built on consensus, then does the vast amount of pornography suggest that we finally approve of it?

the adorno-horkheimer corrective

We have returned with even greater magnitude to the condition that Walter Benjamin voiced in his 1934 essay, “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, when he noticed that the socially liberating possibilities of new media such as film were undermined by the manipulations of the image wrought by the Nazi propaganda machine. We might also revisit Adorno and Horkheimer’s 1944 essay, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception”; it is as relevant as ever.

To Adorno and Horkheimer, the culture industry of popular music, cinema, television and advertising lulls its receivers into a state of torpor, of false pleasure, deluding them that they are safe and free and still have discerning free will. This counterfeit bliss involves a welter of vulgarizing compromises, what in today’s parlance is known as dumbing-down: “a movement from a Beethoven Symphony is crudely ‘adapted’ for a film soundtrack in the same way as a Tolstoy novel is garbled in a film script.” Mass media gives its audience everything and more; the arts are willingly bowdlerized and conglomerated, expurgated or refashioned. In commercial film people expect a hackneyed plot and a certain ending and are disappointed when they do not get it. The same goes for structured temporal and formulaic limitations of commercial music. In a statement that presages Baudrillard they exclaim, “Real life is becoming indistinguishable from movies.” The public are encouraged neither to imagine nor to reason for themselves. The manner in which mass media shields its audience from the plain realities of being human robs humans of the power to create for themselves a happiness external to what has already been defined for them by the mass-marketed juggernaut of the culture industry. If we apply their theory to digital media, we see that while it has positive effects for rogue sites that undermine political censorship and disseminate repressed material (eg dead GIs in bodybags), it is used just as much as a tool for social manipulation, from conservative political agendas to marketing. We know that more people log onto commercial sites, joke pages, personal chat and porn than they do to sites that try to give the truth about world events.

artentertainment

The consequence of this muzak life on art? Adorno and Horkheimer hoped for the possibility for art to sing over the cacophony. One of the ways for art to counter the industry that constantly undermines it is to adopt for itself a critical stance that all but eschews the kind of beauty that hallucinates the gormless public. If not, art becomes as shallow as anything else. Art is always to some extent forced into entertainment since it must give its audiences a modicum of what they know, or else art never has a chance to enter into public discourse and remains rarified to the point of pomposity. But whereas art is supposed to be a creditable form of knowledge, “the culture industry perpetually cheats its customers of what it perpetually promises”, since the real promise is not that we will be led to a better way of thinking, but that we will continue to be entertained. It is barbarism hiding in the sheep’s clothing of civilisation.

More recently, with the rise of the YBA (Young British Artists) phenomenon and its many sensationalist off-shoots, critics and artists have commented that much art is indistinguishable from the entertainment to which it is meant to be significant foil. Society has largely lost its ability to discriminate between knowledge and information, knowledge implying a method, information being just unqualified material, like data downloaded onto a computer desktop.

a strange apathy

To return to the question of the tertiary sector, what is noticeably the case is the production of ideas without a sense of their background. Nothing comes from nothing but this does not stop the diverse production of works of art by young artists, many of whom have no regard, or interest, in their forward trajectory or their provenance. The world we inhabit is a series of bite-sized bits which have no definite beginning but reach an abrupt end. It is curious that the internet encourages a strange form of apathy when so much tragedy is there for the taking. Or perhaps because of that, the uneducated mind doesn’t know where to start.

Grounding the groundless has always been an aim of knowledge. It has two effects. One is to render ideas hard and inert; the other is to provide the correct platform for an effective ‘revolution’ for want of a better word, to take place. Without education all we see are whimpers dressed up as bangs, a rhetorical revolution whose only aim is to state itself: ‘I am here’, like aimless chat on YouTube or an endless vomiting of SMS prattle. Those who use the internet as an end in itself are holding onto a rudder whose direction is permanently being reset, a world that is constantly rebooting before their eyes without them even knowing it.

white noise

For as long as we can remember, the academy has always complained of a crisis. The current one is a lack of support for education and knowledge for its own sake: the simplification of degrees into products, the reduction of students to quotas, the weakening regard for the skills that academics are meant to disseminate. I am not announcing the death of anything. It is hard if not impossible to quell the instinct to make art whether there be art schools or not. The devaluing of humanities and art education will not in any way reduce the volume of things written or art made. Nor am I an apologist for the institution—let me be clear about that. But muffling and trivialising the kind of debate whose task it is for universities to foster and refine will only engender more boring, bad art as transient as entertainment. It will also stifle the platform on which to shape new critical voices (let alone to argue through what constitutes the apt critical voice of today). We already have a welter of raw autodidactic art oblivious to the traditions it’s trying to remake and we already have far too many opinions—all white noise in the end.

Meanwhile, within universities we have flagging self-respect. Students do not know where to go to rebel and lecturers find themselves wearing a dowdy mantle of academicism and ‘tradition’ in their best efforts to keep critical consciousness alive.

RealTime issue #80 Aug-Sept 2007 pg. 18