the nurturing of chinese photography

dan edwards: rong rong interview, beijing

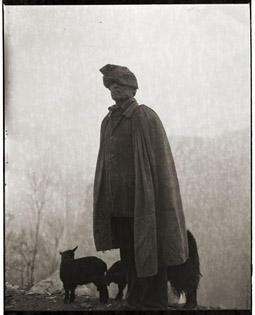

Man with Sheep, 2006, Adou

photo courtesy the artist

Man with Sheep, 2006, Adou

RONG RONG HAS BEEN A KEY FIGURE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTEMPORARY CHINESE PHOTOGRAPHY SINCE HIS PIONEERING WORK IN BEIJING’S ‘EAST VILLAGE’ IN THE EARLY 1990S.

Since meeting his Japanese wife Inri at the turn of the decade, the pair have collaborated on a string of intensely autobiographical photographic series documenting their lives together and the changing nature of their surrounds. In June 2007 they opened the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Caochangdi, on the north-eastern outskirts of Beijing. As well as holding a darkroom, digital studio and library, the centre has hosted artists’ residencies and staged a series of innovative group and solo exhibitions highlighting current trends and talent in China’s emerging photographic art scene.

Dan Edwards spoke to Rong Rong about the centre and the inaugural Three Shadows Photography Award. Dan’s article about Three Shadows can be accessed here.

When did you and Inri first conceive of the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre?

In 2005. Initially it was just a dream for Inri and me. In 2001 I visited many artistic communities across Europe and saw a lot of spaces dedicated to photography. As a photographer I felt they were so lucky to have such places, where you could see work, exchange ideas and find a lot of research material. China is such a big country, but it didn’t have these things—in this respect China was a blank. I didn’t go to a real college to study photography, but experienced a long self-taught process. China doesn’t have a photographic museum or archive, so at least we wanted to establish a library for everyone to use as a basis of communication. Slowly the idea of the centre became bigger and bigger.

Why did you choose this site rather than 798 [Beijing’s most famous art zone, in Dashanzi]?

In 2005 I started looking for a place and in 2006 we started to plan. We went to 798 but finally we chose this site because it is very quiet. Also my company is located near here. Originally this site held a very old building. At first we wanted to renovate the old structure but later we decided to demolish it, and talk to a designer about building a library, café and so on.

Although Three Shadows is an exhibition space, we also have other functions. For example we hold forums and artist residencies. If the artists lived at 798 it might be too noisy. These factors indicated we needed a quiet neighbourhood. So I had a very clear aim, and looked for a site based on that. 798 is currently undergoing very rapid development, and I can see the speed and direction it’s headed in—it’s like a big supermarket. They want to have everything there. So I didn’t think the environment suited our independent gallery.

What were your aims in creating the centre?

The most important question for me was, where is China’s photographic history? On the surface in recent years China seems to have an abundance of photographic history, but in fact it doesn’t have its own foundation or system—there are no photographic museums, archives or collections. The country lacks these things so we wanted to start and slowly build them up, because Inri and I met through photography. In 1999 I had an exhibition in Tokyo, and she came to see it. We wanted to set up a platform to introduce photography to a broader audience and show the beauty and joy of the form. We now have a small permanent collection that is slowly growing.

Do you act as an agent for other artists as well?

Yes, we have some of the functions of a commercial gallery, but we also have many functions a commercial gallery doesn’t have, such as providing residencies, hosting forums, publishing and providing library and darkrooms facilities. We don’t have any financial support from the government—we depend on ourselves. Every penny for running the centre comes from selling our work. Inri and I put all our money back into the centre. We hope the money can eventually go into a public foundation so Three Shadows can become a fully independent institution.

Can anyone apply for Three Shadows residencies, or are they for Chinese photographers?

They are mainly for international artists, as it’s easier for most local artists to come here—although if you are from somewhere far away like Sichuan or Tibet you can also get a residency. We mainly want to provide a bridge for communication between Chinese and international artists. We have already had six or seven foreign artists come through here: American, Spanish, Finnish. When they come here they can produce work and use the library and darkroom. But the most important thing is to communicate with local artists.

When did you and Inri come up with the idea of the annual Three Shadows Photography Award? Was it part of the original idea of the Centre?

Yes, because finding emerging artists with potential is very important. My own experience tells me that in a certain period of your career being encouraged or complimented by others, and having the chance to communicate with other artists, is very important. Of course China has other kinds of photographic awards—official government or commercial awards given by companies. But I think the Three Shadows award is completely different. We have our own conception of the development and language of contemporary Chinese photography.

The press release says you received nearly 300 submissions. Were you surprised by the size of the response?

Not very surprised, because China has such a large population. At the same time, this was the first time we had run the award, so 300 entrants was pretty good. It was hard to narrow the entrants down, but the finalists we selected already know their direction. My original idea was to select eight to ten finalists, but when we saw how many good works there were, we eventually settled on 31. Then we had the exhibition and the international judges arrived to give the award on the basis of the finalists.

Was there a lot of new talent you hadn’t seen before?

I hadn’t seen much of the work before—most of the artists were very new and very young.

The award is open to any Chinese citizen or anyone of Chinese descent, so were there many submissions from outside the mainland?

This year there were not many non-mainland people. Among the finalists there were four—one each from Hong Kong, Taiwan, New York and Germany.

Based on the award submissions and your work here at the centre, do you see any particular trends in Chinese photography at the moment?

Digital techniques are being very widely used. Hand processing is becoming very rare and is slowly disappearing, which I think is a pity. Of course I don’t reject the new techniques, but I think hand processing is very important. Many young people have already abandoned these techniques.

What about at the level of subject matter?

One thing I noticed is that everyone wanted to express their private selves. Unlike older photographic trends that were focussed on society or big topics, younger artists are focussed on their inner world.

When did you first encounter the work of the winning photographer Adou?

In 2008 we started thinking about an award for young artists. The Three Shadows curator Zhang Li went to various places to scout for new talent. He went to many places like Guangzhou and Lianzhou and collected a lot of material. Adou wasn’t part of any formal art festival or exhibition—he had just printed his work and was selling it on the roadside. Our staff saw it and brought it back. He was a designer for ten years, then he quit and became a photographer. When I saw his pictures I found them very attractive—I feel Adou’s photography has the weight of time and history in it. So we found him and said we wanted to hold an exhibition of his work. Originally he just printed his work using a computer, but when I talked to him he agreed to use traditional hand processing techniques to reproduce his pictures. It really suits his work.

So was the Outward Expressions exhibition [at Three Shadows in March-April 2008] the first time Adou had exhibited in a gallery?

The first time. Also the first time he had hand processed his photographs.

In terms of Chinese contemporary art, the focus of the international market in recent years has very much been on painting. Do you think this a reflection of what has been happening at the level of practice in China?

Yes, this is a big problem. Chinese photography is 30 or 40 years, or even more, behind Chinese painting. Photography became an independent artform very late in China. Maybe this has something to do with the Chinese system, because photography has always served the government—photographic themes have always been focussed on the government. In recent years it’s become a bit better, but previous work had no artistic value.

Do you think this is changing? Is Chinese photography developing its own traditions?

On the surface it seems so, but in fact I think it’s not enough, because China doesn’t have good photographic institutions, critics or publications that give people the chance to see original works. There is also a lack of communication—the world’s top photographers don’t have much opportunity to come to China.

Is photography taught in Chinese art schools as an artform?

There are a few courses but not many. I think it’s really important to have an independent college of photography, but China doesn’t have one at present. All the courses are taught by departments within broader art colleges. For example, the Chinese Academy of Fine Arts [in Beijing] has a course in photographic history and the students sometimes have classes in the Three Shadows library. Also Qinghua University [one of China’s top universities situated in Beijing] has had classes here. Something really funny—when the students visited the darkroom, they had never seen an enlarger before. Even more amazing, they had never seen 35mm film before. Most of the students were young girls in their 20s, and they used their digital cameras to take pictures of the 35mm film. I thought it was really funny.

Did you feel the award entrants were very aware of the history and traditions of photography in and outside China? For example were they aware of your work in the East Village back in the early-1990s?

I think they know something, but it comes from the web. They lack contact with original works and other artists, which I think is very important. Looking at prints and original work is very different. Also a working environment where they can communicate with foreign artists is really lacking. Of course they can find a lot of information online, but they lack real experience. Three Shadows can provide this. Society is based more and more on the virtual, but I feel real experience is still very important.

Thanks to Wang Yi for her help translating the interview.

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. web