The object of the game: digital sculpture

Daniel Palmer

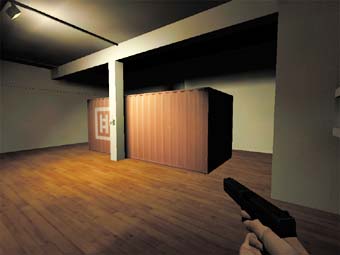

Stephen Honegger and Anthony Hunt, Container (video still)

There’s an emerging niche of visual and sound artists in Melbourne who are actively influenced by computer games and what they represent in contemporary digital culture—which isn’t surprising when you consider the popularity of gaming and Hollywood’s relentless plundering of its imagery; or follow art-game trends in new media art internationally.

Stephen Honegger and Anthony Hunt have worked with the theme of game culture for several years, collaboratively and individually. Soon after graduating with Honours in Painting from RMIT, they installed a Sony PlayStation on a platform at Grey Area, just-out-of-reach, played by whoever was minding the gallery (Gameplay 1998). Hunt has presented facsimiles and ‘doubles’ in various media, while Honegger has sampled game landscapes in his videos, and in Final Fantasies (2002)—with Damiano Bertoli, Amber Cameron, Chad Chatterton and sound artist Julian Oliver—fitted out Gertrude Street contemporary art spaces with 3D sculptural forms lifted from the gaming world (such as concrete blocks and Mario Bros love hearts).

Container, a large-scale sculptural installation at Gertrude Street contemporary art spaces, offered a highly original and sophisticated use of the game logic. More experimental than the form of critique often associated with Australian new media art, Container was more interesting as a result. Entering the gallery, we encountered an object that seemingly didn’t belong: a full-scale rusted metal shipping container, complete with insignia. Container was originally conceived as a 3 screen video projection, but as Hunt confessed, “we were going to have to build lots of walls to make the space dark…and realised a container would be ideal.” Such an imposing art ‘clue’ and a mysterious droning sound from within compels us to look closer. Upon inspection, we discover the container is fabricated entirely from wood, meticulously constructed and painted to match our idea of what it should look like—and precisely matching the iconic image of containers which feature so ubiquitously in computer games.

The dark interior of the container reveals far more, as a video projection immerses us in a narrative generated from the game software Worldcraft. This follows a trend amongst gamers—popularised by mega-games such as Doom (1993) and Quake (1995)—to create and extend existing games using freely available source code (‘shells’) and software. It’s good for the software companies—whole communities develop around their games— fans do the research and development for free. Thankfully, the outcomes aren’t always predictable. The DVD loop in Container begins at night with a first-person perspective onto a detailed, 3D-rendered, pebbled alley at the rear of a warehouse. It’s an aesthetic immediately recognisable from any number of computer games. Clean, jerky camera moves create the sensation of moving through this simulated space. But as the character breaks into the building, we come to realise that what looks like scenery pulled from the latest computer game is, in fact, the gallery itself. What follows is an enticing virtual prowl through the empty upstairs corridor spaces of Gertrude Street artist studios—well known to most visitors.

It’s extraordinary how much mood and realism can be generated from game software. What almost looked like some extraction of hand-held video, as Hunt explained, was all painstakingly modelled in 3D over several months. “It started with the architectural floor plan, and measurements to the millimetre: the door heights, the corridors…everything we needed to know. And then we took photographs of all the surfaces…With modelling, you’re generally just building boxes, and then sticking on a digital image [for texture].” Gertrude Street was the ideal environment for such virtualisation, its corridors and stairs adhering perfectly to the syntax of game modelling. Honegger, who is open about his ambition to work in the game industry, admits that you wouldn’t be able to ‘play’ or interact with Container in its current polygon-inflated form. The point was, “to push it for our own purposes, to do something different with it.”

The narrative moves into surreal mode as we glide down the stairs into the gallery at ground level. The origin of the shipping container is disclosed when the ceiling magically opens and the virtual container slides gently down. The character stalks into the gallery office (complete with rendered versions of the computers, chairs, and catalogues) and collects a handgun foolishly left in one of the office trays. Entering the virtual container, another figure stands—just as we are—watching a screen (now blue and flashing ‘PLAY’). Thus armed, our identification with this character is put under duress. The game has become a ‘first-person shooter’ and it’s too late to intervene: shots are fired, shells pour onto the floor, the figure collapses and blood splashes on the wall. A ‘badly painted’ wall, now revealed as a trace of this gangland-style execution, was the overlooked clue.

Container preserves the basic narrative structure of commercial games—the survival objective and competitive aims—and in this sense is no critique. Yet, experienced alone, it evokes a chilling psychic and temporal displacement reminiscent of one of its inspirations—David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999). Simultaneously alienating and delicious, it adds a rich new dimension to the idea of site-specificity, the gallery, and indeed to the tradition of participatory art.

Container Stephen Honegger & Anthony Hunt, Gertrude Street contemporary art spaces Feb 1 – March 2.

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 31