The pull of the volcano

Gretchen Miller: Maria Miranda & Norie Newmark, Volcano

Volcano, Maria Miranda & Norie Newmark

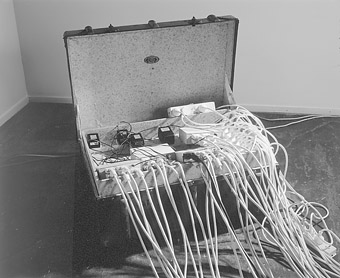

A simply lit trunk sits in a corner. It’s reminiscent of something you might find washed up on a beach, or pushed aside by a lava flow. Faded, but still intact, it has a history. It may well have been the thing you grabbed, stuffing it full of clothes as you tore out the door, just before the volcano erupted. Maybe you dropped it, and by a twist of fate, as you were incinerated, it survived, the slow moving lava taking a different path from where it was hastily flung.

The shape of the island is strange, nearly circular—a mountain like a ring in the sea.

While the experience of Volcano has a similar, touching appeal to wandering the ruins of Pompeii in Italy, there’s also something gently humorous about Maria Miranda and Norie Neumark’s new installation piece, on the island of Stromboli, at Sydney’s Artspace.

The debris spilling from the trunk is not the legs of stockings and arms of sweaters, but the substance of the volcano itself, remembered by the trunk and now transformed as memories often are. Through technological aids we are given a trunk’s memory of the volcano…And because the trunk has seen many lives, so the memories are from many different times.

The trunk is lit by a spot of yellow. From it spews a mass of tangled cables, a lava flow of plastic and wiring, which lead to a collection of lava rocks—in the form of computer monitors, out of which spill and shake various images.

‘What!’ I shouted. ‘Are we being taken up in an eruption? Our fate has flung us here among burning lavas, molten rocks, boiling waters, and all kinds of volcanic matter; we are going to be pitched out…vomited, spit out high into the air…in the midst of a towering rush of smoke and flames; and it is the best thing that could happen to us. Shot out of a volcano at last!

Jules Verne, Journey to the Centre of the Earth

Stones are falling around your ears—they sound like rain on a tin roof, in Neumark’s accompanying sound design. At strategic points around the monitors the roar of the flow has come down through time, down through the wires, as a static hiss, in and out of which fade voices—the gabble and chatter of people and bodies before, during, after. They’re speaking in the Stromboli dialect, something like a siren’s call, urging you closer, drawing you through the rubble, to tease out the meanings. It’s a trick—by now they have nothing particular to say, but to cry out their grief and love, inarticulate but still genuine, over time.

It seems that Hephaestus, being displeased one day, had taken the island of Thira in his hand and thrown it some distance, like a stone.

Maria Miranda has manipulated a series of static pictures, playing with the moment when you’re really not sure whether or not the earth has moved, if the trembling you’re feeling is lust or fear.

As you move in closer to the volcano, the images shift, and texts circle around, shifting between screens/stones. The radioactive heat has rendered them distorted, but the message is clear. We’re discovering the seductions of the notion of ‘volcano’, as did Krafft and Krafft, the vulcanologists who were famously consumed by Unzen in Japan, erupting in June 1991 just as they were taking photographs. The images could be, like the trunk, what remains, the camera thrown clear…

Eugène Ionesco also felt the pull of the volcano, and wrote the preface to Krafft and Krafft’s famous book of the same title as this installation—he tells us the myth of Stromboli’s birth in fits and grabs, while Jules Verne’s adventurers occasionally emerge through its centre, relieved, after their travels underground. And Stromboli’s also the island where Miranda’s grandfather Giuseppe Russo was born. Russo left for Australia as a young man and never returned, the tip of the volcano the last thing he saw. But in an ironic twist, as his eyesight disintegrated, he was left with an impression of the world somewhat in the shape of a volcano—a ring of clarity around a blurred centre.

It had fallen in the sea not far from Italy giving birth to the volcanic island of Stromboli. But in uprooting the center of the mountainous island, Hephaestus had left its edges, with the volcano in the middle. They say that if one were to put Stromboli back in its former place, it would take up precisely that part of the island that was pulled up.

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 39