The rewards of risk

John Bailey

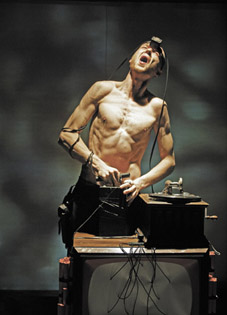

Steven Ajzenberg, Nick Papas, Not Dead Yet

photo: Sandra Matlock

Steven Ajzenberg, Nick Papas, Not Dead Yet

Rawcus & Born in a Taxi

During an Australian tour last year, New York dancer/theorist Bill Shannon expanded upon his performances by incorporating discussions of a particular politics he saw as essential to the reception of work by those with bodies outside of the social category of ‘normal.’ Shannon, on crutches since the age of 5, articulated an aesthetics of “failure and heroics”—a kind of grass-roots discourse of performance as becoming, rather than being, of process over product. Every performance is an attempt, and ‘failure’ is not an aberration but a component of expression with its own significance. The majority of live performances seek to conceal the attempt in favour of the end result, but differently-abled bodies draw our attention to the normative politics of such an endeavour. The distinction between what could be termed the ‘try’ and the ‘act’ is something that separates sports, circus, comedy and some forms of dance such as breakdancing or tap from more traditional modes of performance which seek to pave over the effort that goes into delivery.

Viewing performers with disabilities can reveal some of the underlying assumptions we bring to our interpretation of all performances. Do we judge disabled performers differently? Probably. But works like the recent Not Dead Yet can help us to understand this as a productive way of seeing. Judging an actor’s ‘ability’ here takes on a new dimension: after all, we often praise or condemn a non-disabled actor’s ‘ability’ in a role without considering the kinds of politics which might surround such interpretation.

The cast of Not Dead Yet is made up of contemporary physical theatre ensemble Born in a Taxi and Rawcus, a company featuring performers with and without disabilities. Born in a Taxi’s Penny Baron devised the piece after a South American journey which introduced her to Aztec and Incan cultures’ worship of disabled individuals as guides into the afterlife. Not Dead Yet is a group-devised response to death and the hereafter, and though there is a loose narrative thread to the piece (a woman’s slow journey after death), the piece is largely composed of a series of disjointed responses to the overall précis. Part of the work’s enjoyment comes from realising the questions posed by each scene: how would you least like to die? What are you afraid of leaving behind? What would you most hope the afterlife to hold for you? This last question underscores one of the piece’s most moving sequences, an initially cryptic scene in which performers throw paper planes, play in a sandpit, or slow dance together. When blind and wheelchair-bound Ray Drew, who was himself pronounced technically dead after being electrocuted, begins to cry “I can see again! I can see again!” it becomes apparent what is being explored here. Moreover, the emotional affect of this scene is so powerful precisely because it acknowledges the embodied experiences of its participants, both disabled and otherwise.

Theatre@Risk

Australian theatre has sometimes struggled to find a footing when dealing with urgent political issues. The tendency towards didacticism must be tempered with a realisation of the sophisticated theatrical vocabulary of audiences, many of whom are sensitive towards overtly polemical narratives. Theatre@Risk has already demonstrated an ability to address contemporary affairs with delicacy in mounting recent works from abroad (Terrorism; Arabian Night) and original productions (The Wall Project; 7 Days, 10 Years). Stalking Matilda engages with the politics of paranoia and the treatment of refugees, ostensibly exploring the mysterious death of its heroine as a means to uncover a society of trenchant racism, institutionalised xenophobia and ultimately explosive class tensions. An ensemble of uniformly strong performers creates the social environment in which the doomed Matilda and her immigrant husband move, and as we learn more about the 2 we begin to question our own complicity in such a perilous state of affairs.

While the politics of stalking itself offers fruitful ground for a theatrical work, the title of this piece initially appears somewhat misleading. A trenchcoated voyeur occasionally hovers at the fringes of proceedings but only rarely becomes a notable figure. As the story unfolds, however, it begins to appear as if the audience itself is the stalker, looking in on, at times, obscured views of the central character’s life, piecing together a distorted composite image of her complex existence. It is a testament to both Tee O’Neill’s writing and Chris Bendall’s direction that the idealised, glamour model portrait of Matilda is always rendered only partially, while remaining a distinctive and many-levelled characterisation. As Matilda herself, Jude Beaumont creates an entrancing intensity for a character who is in other ways composed only of surfaces. In this she is matched by Rob Jordan, whose charismatic portrayal of Matilda’s husband Suleyman is both sympathetic and bold. Staggering through a city street, clutching a rag to an open stomach wound, it is apparent that Jordan understands the importance of subtlety in what could otherwise have been an overplayed death scene. In this, as in most of Stalking Matilda, Theatre@Risk has once again produced a keen-edged and incisive investigation of local and international politics and the pressures which place both social and personal ties in crisis.

Stuart Orr

Stuart Orr, Telefunken

photo Jeff Busby

Stuart Orr, Telefunken

The recent remounting of Stuck Pigs Squealing’s Black Swan of Trespass and the commissioning of Telefünken are part of Malthouse Theatre’s new Tower Theatre program. Independent artists and companies are invited to stage existing or new works in the intimate venue and are given creative freedom to present their final product without interference from the company. At the same time, they are required to provide the kinds of progress reports and budgets which would be expected of a larger, professionally mounted production, thus schooling emerging artists in the kinds of practice which await them later in their careers. It’s a gamble, but one which has so far resulted in strong works which add a vital energy to the Malthouse calendar.

Telefünken is a solo show devised and performed by Stuart Orr and directed by Barry Laing. I’m not sure if Orr was inspired by author Thomas Pynchon’s magnificent opus Gravity’s Rainbow, but this was the text which most forcefully impressed itself upon my interpretation of the piece, and that’s a potent recommendation. Like Pynchon’s notoriously difficult work, Telefünken re-imagines the closing moments of World War II through a cacophony of voices and embedded narratives. Trapped within a Berlin moviehouse as Russian tanks roll into the city, the audience is confronted by an SS soldier eager to relate the story of his life, but the manic deserter does so by both describing and enacting his tale as a movie with storyboard, commentary and dialogue, amongst other framing devices. The plot unfolds through this series of competing mirrors, and Orr’s incarnation of Mann, the increasingly erratic storyteller, emphasises his position as the postmodern Unreliable Narrator, who may be mad, sick, duplicitous or forgetful. We are never provided a safe position from which to make sense of these events, instead attempting to navigate this explosive terrain in the same method as our guide.

Like many of the postmodern authors of the late 20th century, Orr also offers us Telefünken as an encyclopaedic narrative, one which matches densely textured detail with an impressive scope. The many streams which carry through the piece include Northern European mythology, reality television, the modern psychology of crowds and the mutability of history. Orr plays a multitude of characters, and though his accents are impressive there is room for development in the area of vocal delivery. This quibble aside, if the rest of Malthouse Theatre’s Tower season matches this level of brave innovation, few will argue with the direction the company has chosen to take.

Not Dead Yet, directors Penny Baron, Kate Sulan, designer Emily Barrie, lighting Richard Vabre, deviser-performers Steven Ajzenberg, Clem Baade, Kellyann Bentley, Ray Drew, Rachel Edward, Nilgun Guven, Carolyn Hanna, Valerie Hawkes, Nick Papas, Kerryn Poke, Louise Riisik, Jolan Tobias, John Tonso, presenters Born in a Taxi, Rawcus Theatre Company; Theatreworks, St Kilda, Sept 15-25;

Theatre@Risk, Stalking Matilda, writer Tee O’Neill, director Chris Bendall, performers Jude Beaumont, Irene Dios, Odette Joannidis, Rob Jordan, Toby Newton, Jeremy Stanford, designer Kelle Frith, sound Kelly Ryall, lighting Nick Merrylees; Theatreworks, St Kilda; Aug 5-21

Telefunken, writer-performer Stuart Orr, director Barry Laing, Tower Theatre, Malthouse. Melbourne, Sept 14-25

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 37