the shadowcatchers: australian cinematographers documented

tina kaufman: interview, martha ansara, calvin gardiner

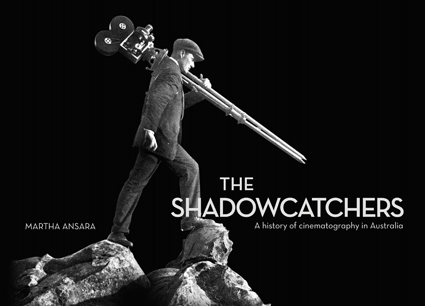

book cover The Shadowcatchers, A History of Cinematography in Australia

THE BOOK WILL BE BEAUTIFUL. IT’S COFFEE TABLE BOOK SIZE, AND IT’S FILLED WITH OVER 380 PHOTOGRAPHS OF AUSTRALIAN CINEMATOGRAPHERS WORKING ON FILM SETS FROM ALMOST THE BIRTH OF CINEMA TO THE PRESENT.

There’s a rich and detailed text, covering the history of film production in Australia but told very much from the cinematographers’ perspective, and there are fascinating and often very funny biographical sketches of many of those who have worked behind the camera throughout that history.

It’s The Shadowcatchers: a Photographic History of Australian Cinematography, and when it is finally published next month it will be the culmination of an eight-year labour of love by the Australian Cinematographers’ Society and, in particular, ACS members Calvin Gardiner and Martha Ansara.

In the very comfortable ACS clubrooms in North Sydney I talked to Gardiner and Ansara about how the book came about. (These are clubrooms which are well used by the very involved ACS members; there’s a terrific library, excellent screening facilities where they view one another’s work and an extensive and fascinating collection of donated cameras and other film equipment.)

It’s well known that Australian film crews are hugely respected in the industry, both locally and overseas, cinematographers particularly so. (There are five Australian Academy Award-winning cinematographers: Dean Semler, Andrew Lesnie, Russell Boyd, John Seale and Dion Beebe.) In fact, as I say to them, the one person who has been absolutely essential to the making of a film since filmmaking began has been the one behind the camera.

Calvin Gardiner (“a superb cinematographer,” says Ansara) who was inducted into the ACS Hall of Fame in 2009, is a committee member of both the NSW and Federal Executive and was elected as NSW President in 2008. His father, Jack Gardiner, was also ACS Federal and State President.

lunatics, obsessives & individualists

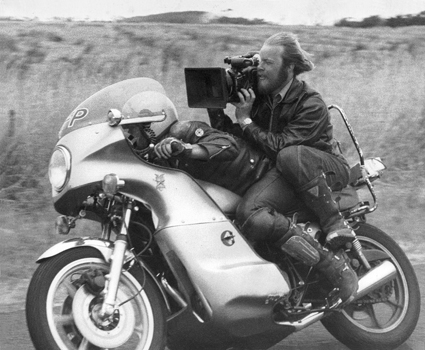

Terry Gibson (driver), David Eggby (DOP), Mad Max (1979)

courtesy David Eggby

Terry Gibson (driver), David Eggby (DOP), Mad Max (1979)

Gardiner says, “that’s what the book is really about; the cinematographers—their lunacy, their obsessiveness, their individuality. It’s about the people; what they do, how they feel, what they do to get the job done. It tries to find out, but doesn’t quite answer the question, why do they have such high standards? It used to be a fairly carefree, larrikin, fuck you mate, I’ll do it my way attitude that prevailed,” he explained, “and it’s still there, but underneath, more concealed.” “Perhaps it is, as John Seale says, ‘something they put in the beer’,” adds Ansara.

While she says that Gardiner really instigated the book, they both put the idea to the ACS Committee, back in 2004. “The original idea was to have it ready for the 50th anniversary of the ACS, which was founded in 1958; but it was much harder, and took much longer, than we expected,” she explained.

from oral origins

Ansara had interviewed many cinematographers while recording their oral histories and this was a great starting point for the project. One of the first women in Australia to work as a cinematographer, she later became a director and producer of prize-winning social documentaries, also teaching film production and writing historical and critical articles on film for a range of publications. She was the founding convener of the Film & Broadcast Industries Oral History Group, and has contributed nearly 100 oral histories to the National Film & Sound Archive.

How did that start? I asked. “In 1977, when I was a cinematography student at AFTRS, we were required to write a paper, and I wanted to write one that would teach me something about the close-knit group of cinematographers who seemed to dominate everything in those days and who, it seemed then, would never accept a woman into their ranks,” she explained. “At that time, there was so little written information (still largely the case) that I had no other choice but to ask the older cinematographers to tell me their histories. Among them was Bill Trerise, who started in film as a spool boy at the Lyceum before the First World War. It was he who said, ‘They used to call us the Shadowcatchers,’ and so that’s what I called my very naive paper—and now this book.

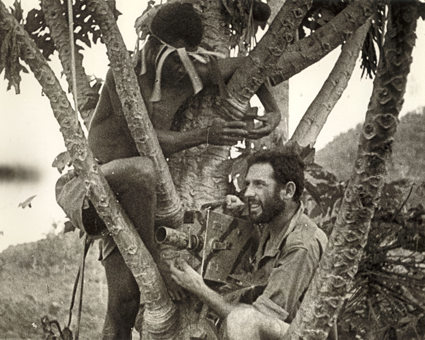

Damian Parer, cinematographer

“It turns out, however, that any woman who demonstrates real ability and love of cinematography is accepted despite the prejudice. And today, the men who run the ACS, brought up as they have been in the fiercely masculinist culture of Australian cinematography, make that extra effort to respect and promote the work of women cinematographers. And I respect them all the more for doing so because they act out of a consciousness which doesn’t come naturally and in some ways goes against their upbringing. In the book, there is quite a lot about this upbringing—the apprenticeship in attitudes as well as skills—which, until relatively recently, was how young teenage boys became cameramen,” she says.

integral to the industry

Although she’d done the oral histories and talked to people who told her about how things really were, Ansara said that once she began the research she discovered just how integral to the industry the cinematographers were. “They shot the film, they directed, they had very little film so they’d shoot so that everything they brought back to the editor was useful. Up to the 60s,” she said, “the industry was actually driven by cameraman-directors, who not only made the films but formed companies. Most of the filmmaking was in reality workplace, corporate or industrial documentaries, commercials, filmmaking that lent itself to such small-scale operations.”

“In fact,” added Gardiner, “the production of commercials actually underpinned and supported local production until it was lost through the free trade changes, when people who didn’t understand its importance didn’t fight for its retention—although it was probably doomed, anyway. In the book we highlight the role of commercials and their importance in the wider industry—you really get to hone your storytelling skills when you have to tell a story in 15, 30, or 60 seconds!”

the making of shadowcatchers

“Producing the book,” Ansara said, “was like making a film. First we gathered our material—the interviews, my background research and over 4,000 pictures. Then we did an edit, choosing the photos we would use and organising them, and then we ‘added sound’—the text. It’s just like a film, except that it doesn’t move.”

And how did they get the photos? “We put out appeal after appeal to the members; we asked for great photos that were good in themselves and said something about the art of cinematography—and we got thousands,” said Gardiner. “Martha also researched the picture archives of the NFSA and Film Australia and found some great images, and we got some from the War Memorial. And still pictures kept coming in. We literally looked at over 4,000 photos to find the 380 that are in the book, what we hope are really good pictures that satisfy the criteria we’d established.”

“And getting the captions right! You’d sometimes have to practically dig someone out of their grave to get the correct details,” said Ansara, who only recently discovered a vital piece of information for a caption when chatting to someone at the Railway Film Festival at Eveleigh. “Luckily,’ she added, “some ACS members are amateur historians with stupendous memories.”

Much time was spent in checking captions, facts, redoing scans because they weren’t good enough. There was the drama of changing printers and the search for a better black. As Ansara explained, “cinematographers love their black! But really we knew we had to take a great deal of care, as this is a once in a lifetime production for the ACS, and it has to be as close to perfection as possible.”

the risk-takers

“While we all love looking at the pictures,” Ansara thinks that “really the book is about the human side of cinematography, about the relationships, about how people get to see all those amazing places in Australia. Because that’s what they get from shooting films—they go down coal mines and inside really strange houses and into the lonely outback. And tales of danger, and even death, just don’t deter them a bit. We have some pictures showing the incredibly dangerous situations they’ll get into, just to take a shot. They laugh at danger, do things you’d never do in normal life to get a picture. The obsession is to get the best picture possible, however possible.”

As Gardiner observed, “cinematographers are like a bikie gang in their relationships—the tight knit male group, the nicknames. But gradually women and people of non-English speaking background appear in the mix. There’s a background of collectivity, of independence, and of real pride in the work.”

Martha Ansara, The Shadowcatchers, A History of Cinematography in Australia, Australian Cinematographers Society, 2012, 288p, soft cover $66, hardbound limited edition signed by Academy Award-winning Australian cinematographers, $250; May launch date to be announced.

RealTime issue #108 April-May 2012 pg. 17-18