The Simpsons will save us

Ben Brooker: STCSA & Belvoir, Anne Washburn’s Mr Burns

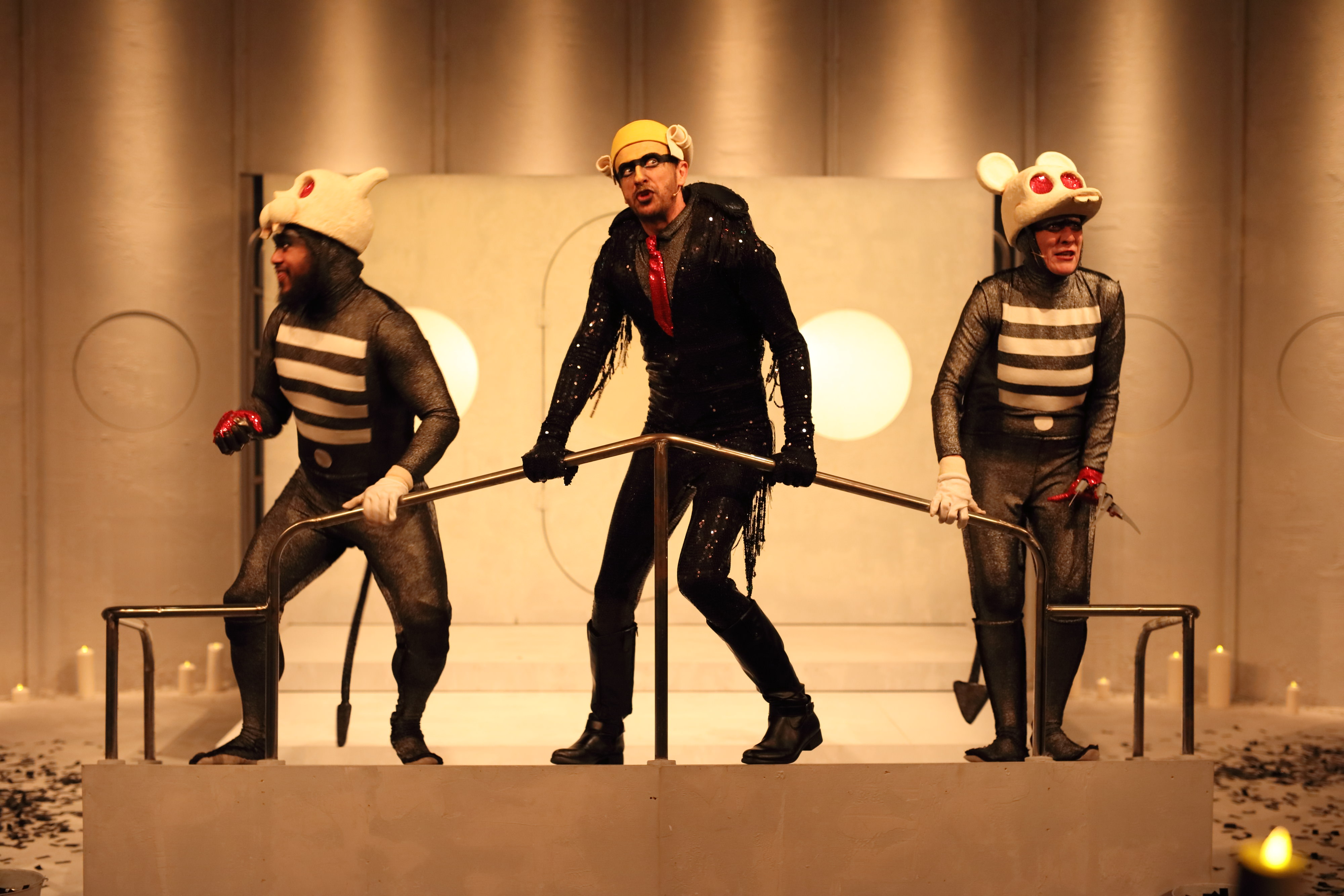

Mr. Burns, State Theatre Company of SA, photo Tony Lewis

Spread across an ad hoc arrangement of indoor and outdoor furniture, four people huddle around a fire. A fifth person sits away from the group, both a part of it and apart. There is the sound of crickets, and of a river running. We are in the near, “post-electric” future, somewhere in the Eastern United States—an Appalachian forest perhaps. Matt (Brent Hill) is trying to remember an episode of The Simpsons, 1993’s Cape Feare, a parody of the 1962 film Cape Fear and its 1991 remake (both of which, signalling the play’s manifold layers of meta-textuality, are based on John D MacDonald’s 1957 novel The Executioners).

In fits and starts the group pieces the episode together from memory, imperfectly recalling its myriad gags and pop culture references, aping the cosily familiar intonations of the program’s voice actors. Another survivor of the catastrophe that has befallen the country—a total power outage has caused multiple nuclear plants to shut down, leading to fires and explosions (or possibly the fires came first, nobody seems to know for sure)—is assimilated into the group, having winningly provided a final, elusive quote from Cape Feare.

The American linguistics professor Mark Liberman wrote, “The Simpsons has apparently taken over from Shakespeare and the Bible as our culture’s greatest source of idioms, catchphrases and sundry other textual allusions.” It is a related idea—The Simpsons as a sort of ur-text for the post-apocalyptic era—that underpins Anne Washburn’s play, workshopped in 2008 and first produced by US company The Civilians in 2012. Much of the first act’s dialogue is based on group improvisations in which the actors were tasked with recreating a Simpsons episode from memory.

Mr. Burns, State Theatre Company of SA, photo Tony Lewis

In the second act, set seven years after the first, the program’s cultural currency is reimagined as an actual economy, a post-capitalist black market trading in pop cultural intellectual property—half-remembered ads, sitcoms and hit songs—fashioned into entertainments staged by competing companies of amateur players. In this, there are echoes of other texts—Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron (c1351), Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) and especially Emily St John Mandel’s post-apocalyptic novel Station Eleven (2014)—that similarly assert, to paraphrase Philip Pullman, the pre-eminence of story in our hierarchy of needs after food and water, shelter and companionship.

The third and final act, taking place 75 years later, dispenses with the previous act’s naturalistic and demotic modes, recasting cultural memory as liturgy by way of musical theatre (one of the many homages of Cape Feare is to Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera HMS Pinafore) and a sort of multi-generational Chinese Whispers. Anne Washburn’s pop- and rap-mining lyrics, in combination with Michael Friedman’s genre-hopping score (played live by multi-instrumentalist Carol Young), add a further layer of quotation as a chorus of shades—nightmarish distortions of The Simpsons’ principal cast decked out in designer Jonathon Oxlade’s renaissance-style costumes—blurrily recreates Cape Feare’s climactic houseboat scene. Significantly, it is the titular Mr Burns, emblem of corporate America and owner of the Springfield nuclear power plant, who is cast as the villain, replacing the original episode’s criminal mastermind Sideshow Bob.

Mr. Burns, State Theatre Company of SA

photo Tony Lewis

Mr. Burns, State Theatre Company of SA

It is an extraordinary, richly theatrical sequence—impeccably staged by choreographer Lucas Jervies and director Imara Savage, not for the first time demonstrating her affinity for high concept comedy—that signals not only The Simpsons’ primacy as an enduring cultural touchstone, but the ability of story, rendered as mythology, to outlive civilisation itself. (In The Decameron, a group of people fleeing the catastrophic effects of the Black Death hole up in an isolated villa in the Florentine countryside and swap 100 stories.) The late John Berger, drawing on Walter Benjamin’s famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” suggested in Ways of Seeing that “[w]hen the art of the past ceases to be viewed nostalgically, the works will cease to be holy relics.” For all Mr Burns’ irreverence and teasing metatheatricality, Washburn shows us, I think, the flipside of this idea—art, in its dominant 21st century form of pop culture, as holy relic in an age when the means of mechanical reproduction have almost entirely broken down. In this way, too, I think the play can be read as a love letter to theatre, to its rituals of mimesis and collective experience. No doubt Washburn’s credible vision of a ruined United States—rendered here by Oxlade with commendable austerity and, especially in the second act, an inventive sense of making-do—is a sobering one, but this is not The Road. There is hope, even relief, in the play’s depiction of a return to a kind of primitivism, a sense perhaps of the necessary closing of a circle.

Anchored by music theatre specialists Mitchell Butel, Esther Hannaford and Brent Hill—the latter fresh from a fine performance in Sydney Theatre Company’s Chimerica, in which he played another American—the cast are uniformly excellent, convincingly transitioning from the first act’s claustrophobic unease to the play’s all-singing, all-dancing conclusion. Put like that, Mr Burns sounds like an overstretched exercise in the ironic subversion of dystopian tropes but Washburn’s writing, however knowing or freewheeling, is buttressed by a moral commitment that feels genuine. As President Donald Trump passes his 100th day in office, it’s a little too easy to say that this is a play for our times.

Mr. Burns, State Theatre Company of SA, photo Tony Lewis

State Theatre Company and Belvoir, Mr Burns, writer Anne Washburn, score Michael Friedman, director Imara Savage, designer Jonathan Oxlade; Space Theatre, Adelaide, 22 April-13 May; Belvoir, Sydney, 19 May-25 June

RealTime issue #138 April-May 2017