The slow retreat of reality: liveness in Melbourne performance

Looking back on the decade or so of Australian performance that I witnessed between 2005 (when I moved here) and today, what struck (and has long been striking me) as most notable has been the slow retreat of liveness—both as an aesthetic, dramaturgical concept, and as an understood fact of life.

I cannot say much about the 1990s: I wasn’t here. But the performance I grew up on was a theatre that increasingly poked holes in its own fiction: the Forced Entertainments and Martin Crimps of this world were reflecting on stage the self-referentiality that Tarantino, Fincher and, later, Kaufman brought to film. The 1990s story-telling existed between inverted commas: referencing tropes and genres while knowing full well that they were untethered from ‘real experience,’ whatever that might be. The artists who left the biggest impression on me at the time were feminist playwrights Sarah Kane, Ivana Sajko and Biljana Srbljanović, who were consciously using the frame of a stage performance to deconstruct national and patriarchal myths, all while deconstructing mimesis. Alongside them, body art and physical theatre, with echoes of Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater, were trying to bypass mimesis altogether, and find some sort of truth in pure co-presence of performers and audience.

In Europe, two overarching concerns were challenging mimesis in a kind of counterpoint: on the one hand was a sense of profound unreality of mass media. Every day, we were receiving our news through the one-way stream of television images, images without context and without potential to anchor themselves in our daily reality: wars, famines, oil spills, distant lands, all disappearing at the click of the red button. We were being told, through the same small box, that ‘we’ as a ‘nation’ were responding to these events with armed forces, aid convoys or disinterest. The overarching affect was of a complete lack of a sense of agency. The war in Bosnia exacerbated this cynicism pecisely because it was happening so close, yet there was no way to make sense of it on TV. Mass media was creating a type of situation in which bearing witness to atrocities, instead of enabling us to intervene, was being used to create a kind of spectatorial event. Is it any wonder that we responded with a profound sense of detachment from storytelling?

An antidote to this sense of profound unreality of mass media was the undeniable, unshakable reality of live performance. Writing about this moment in performance, Hans-Thies Lehmann would later note that while a flickering image of a chair is a material sign of sorts, it is precisely not a material chair. In theatre, the sign and the thing are as close as they can be: on stage, a real chair is representing another real chair, a real person another real person. When the performer is tired, they sweat real sweat. When they are cut, they bleed. As Heiner Müller said, “And the specificity of theatre is precisely not the presence of the live actor but the presence of the one who is potentially dying.” This was a comforting thought, given the context.

Melbourne theatre lagged behind. In 2005, when I landed, mimesis was still going strong and going unquestioned. This seemed strange and not quite right, given the political context. The Australia that I arrived in was John Howard’s country, and it occurs to me now that during that time we witnessed Australian media’s own precipitous divorce from fact-based reality. Rewriting of lived experience with the Children Overboard scandal, rewriting of international law with multiple innovative ways of locking up refugees, rewriting of legal process with the Australian Wheat Board affair this was top-down postmodernism of the highest order. (It was also gaslighting on a national scale, but we didn’t then have the word.) I knew this sense of unreality; that was why theatre had become such a cultural force for my generation in Croatia. And yet, Melbourne Theatre Company was staging West Wing entertainment. It was staging Don Juan in Soho… It was Sydney that responded most ferociously to John Howard, probably thanks to its long history of mixed-media live performance. Version 1.0 created theatrical reenactments of these implausible television performances, turning them on themselves with something between detached puzzlement and burning rage (A Certain Maritime Incident and Deeply Offensive and Utterly Untrue). Early post and Team MESS followed on, challenging the mainstream semiotic constellations of the time.

There was no such rage in Melbourne, but something else was emerging. From 2005 until 2010, Kristy Edmunds’ Melbourne International Arts Festival (MIAF)and Arts House recently established by Steven Richardson brought in a short, sharp dose of postmodernism: British live art and American postmodern performance. Within just a few years, Melbourne had its first appearances of Ariane Mnouchkine, Romeo Castellucci, Jérôme Bel, Ontroerend Goed, Dood Paard, dumb type, Forced Entertainment… Within a year or two, their methods percolated through Melbourne’s independent theatre, always vibrant and increasingly fed up with MTC.

Melbourne’s theatre at the time seemed to me strongly influenced by lyrical body work that I associated with Grotowski and Bausch’s Tanztheater, grounded in an echo of Appia’s symbolism, with emphasis on controlled presence in performance and otherworldly sets. That mode of performance never changed; Melbourne theatre never collectively discarded mimesis. Small independent companies, such as Hayloft Project, Black Lung, Adena Jacobs’ Fraught Outfit and the work commissioned by Malthouse Theatre under Michael Kantor and Stephen Armstrong, instead absorbed the selective breaking of illusion they saw in overseas work and responded by widening the gap between the signifier and the signified. ‘Theatre theatre’ found its inverted commas.

The years that followed saw a rich exploration of illusion in narrative story-telling. Directors turned to playwrights such as Ionesco, Beckett, Bergman and Marius von Mayenberg, framing their exploration more as broadly existential than narrowly political (less ‘mass media is lying to us’ than ‘what is real anyway?’). There was also a marked shift towards retelling Jewish and central European stories, as if in an attempt to restore something missing from the Anglo-Australian narrative of who we are. Forms from puppetry, circus, dance, physical theatre, and visual installation, video art and sound art all entered theatre, as did carnivalesque as a mode of event presentation. This dovetailed interestingly with an international shift towards materiality and the performance as a social event. Pivotal here, I think, were the first appearances of Heiner Goebbels (MIAF 2010) and Ontroerend Goed (Arts House 2009): the latter for incorporating children, the former for its lesson in using props. (Suddenly, everyone was working with children, everyone’s sets were artfully collapsing.) Relational performance came out of this: Melbourne’s interest in live art coalesced seemingly entirely around participation, with significant works created by one step at a time like this, Triage Live Art Collective, Aphids, Field Theory, Lara Thoms, Tristan Meecham, and Luke George and BalletLab in dance. By 2013-4, there was a sense that every theatre outing might involve being asked to climb into bed with the performer. Some had very tangible social outcomes, such as Tristan Meecham’s series of dance classes for LGBTI elders, and the Coming Back Out Ball.

The playfulness of this wave of participation was not apolitical, though it was profoundly unrelated to national politics. Melbourne is a large town, rather than a sprawling metropolis, and the sense of a localised community is strong. Works such as one step at a time like this’s en route or Triage’s Take To Your Bed seemed to strive to create a small, tangible time-space in which participants could have a genuine encounter. Live art became a world designed at a human scale, a series of comfy rooms in which a chair was not only a real, material chair, but it was a site of a real encounter, not a representation of one.

At that same time, smartphones and social media were becoming ubiquitous, and virtual and embodied forms of sociality were starting to bleed into one another. The first flash mobs appeared, coordinated on the Internet. 2011 saw London riots, the first in which communicating via social media made it possible for the protesters to disperse at will and regroup once the police had passed. Soon thereafter, there was Occupy Wall Street, and then Twitter. The relationship between one’s virtual persona and your material, ‘real’ behaviour was revealed as deeply unstable. The comforts of relational performance were perhaps less about the beds and the cups of tea and more about affirming one’s undivided, individual identity—identified not by an avatar, date of birth or IP address, but by a smile and a stroke of the hand.

In 2012, at SXSW, Bruce Sterling spoke about his frustration at retro-ness (“the belief that authenticity can only be located in the past”), which he saw exemplified by the then-trendy aesthetic of op shops, artisanal fashion and blackboards in cafes. Rebelliously, he proposed the New Aesthetic, a unifying term for a culture he saw emerging, of 8chan memes, pixelated sculpture and ubiquitous GPS driving directions. What if the digital is erupting all around us and should be embraced, rather than feared, he asked.

Wrapped in my live art cocoon, I did not notice the New Aesthetic, but in 2013 I became fascinated by dancer Angela Trimbur on her YouTube channel. Trimbur created a series of short videos titled Dance Like Nobody’s Watching, in which she dances to a song in a public space: an airport, a laundromat, shopping mall. We and she can hear the music; the passers-by, however, can’t and are confused as to what she is doing—their reactions are indispensable to the video’s effect.

Trimbur had been called ‘a one-woman flash mob,’ which struck me as unnervingly accurate. By this time, flash mobs had lost much of their original Dadaist joyfulness, becoming heavily rehearsed performance with a view to a long shelf-life on social media. What had started as an intervention into public space became smiling into the camera. Trimbur, too, was smiling at the camera at the expense of any meaningful engagement with the people and places in her surroundings, which in the videos became flattened into signifiers of themselves: interesting to Trimbur only as representing the ‘people’ and ‘public space.’

Here we had a complete reversal of the relationship between ‘reality’ and live performance than I had long taken for granted. In the 1990s, it was understood that our physical reality was unmediated, and its media representation was, well, mediated. But Angela Trimbur danced in public not as a way of creating a live performance, but as a way of creating an intended viral video. The mall, the street, the people of her city were only interesting as props: the real social interaction that Trimbur was attempting would be in the hundreds of loading bars on hundreds of viewer screens. If the aim of political art not long ago was for us as citizens, as artists, to engage with cameras, television and newspapers because of an effect we hoped to achieve in the real world, that aim was here fully reversed.

Trimbur is not a performance artist (I last spotted her as an actor in a Netflix film), but her work heralded a shift away from liveness and towards the internet that has gradually spread through the performing arts. Not long ago, the very essence of live performance was considered to be the unmediated co-presence of performing and spectating people in one room. Now, creating work for Instagram or Facebook is seen as indispensable. In Melbourne, it has led to a gradual shift towards a theatre where the live component seems to matter a lot less than the digital record that the performance creates. It has also meant that, increasingly, ‘participation’ involves the audience’s smartphones, not hands and feet. Around the world, it has meant a pivot to video.

It does sometimes feel like we’re living in a time where live performance has been eaten alive by its own documentation; or perhaps marketing. Unfortunately, as Peggy Phelan has pointed out, performance’s only life is in the present, and once it’s gone it’s gone; whereas websites, YouTube videos and photographs live on. For the coming generation of artists, there may be anxiety in the idea of working hard to create complex works that disappear at the end of the night. However, it is this excess of effort and labour that gives value to this artform. A live performance is a heightened unit of reality, made tighter, denser, richer in meaning. It is a singular event, bracketed by the words ‘you had to be there.’ The low-temperature plug-and-play of social media, with the ‘repeat’ button at the end of each short experience, is not something that one will ever describe with ‘you had to be there.’

–

Commissioned by RealTime, this essay will form part of an upcoming book by Jana Perkovic and Andrew Fuhrmann critically documenting the period 2005-2015 in Melbourne theatre and performance.

Read about Jana Perkovic here.

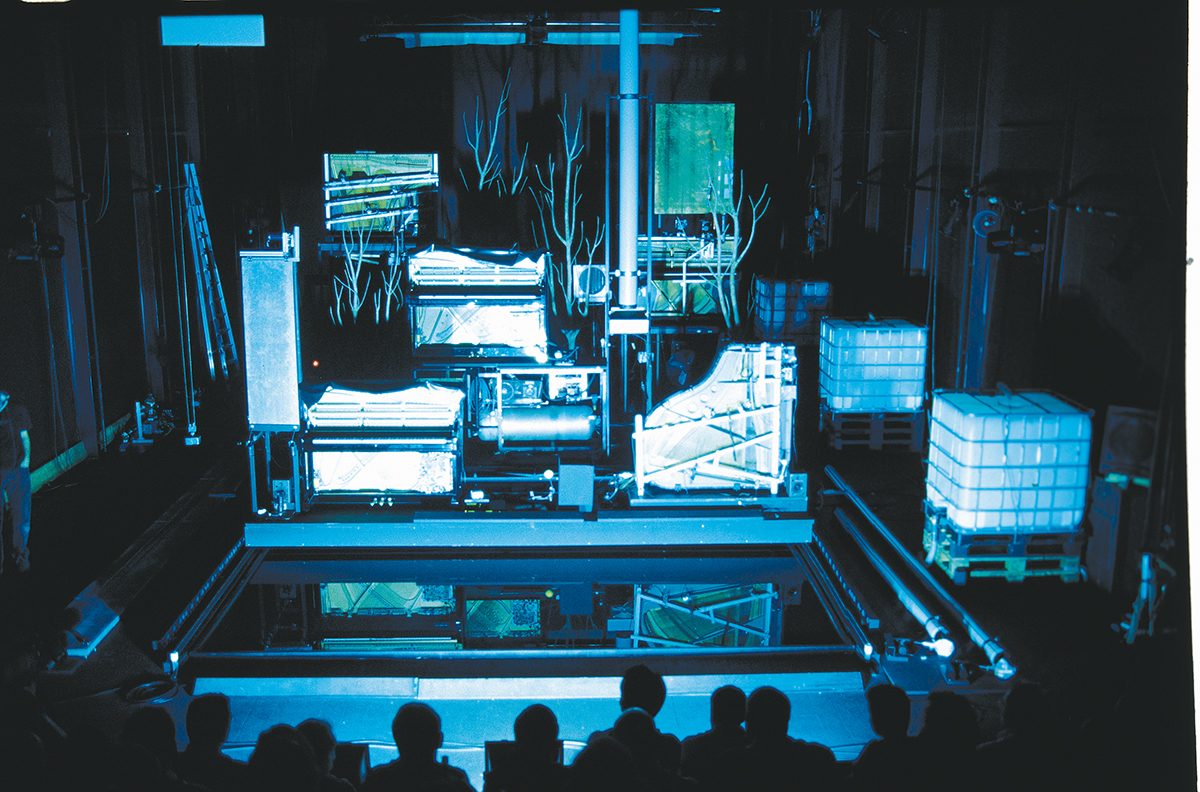

Top image credit: Thrashing Without Looking, Aphids, photo Ponch Hawkes