The thrill of a cut-above festival

Keith Gallasch: Passion, Woyzeck, Meow Meow’s Little Mermaid, Double Blind

I’m reeling with exhilaration and exhaustion, still immersed in much of a far, far better than usual Sydney Festival right to its last days. Anna Teresa De Keersmaeker’s FASE, with the choreographer performing, yet again proved itself a 20th century classic while her Vortex Temporum revealed a gripping, further evolution of her engagement with remarkable music (score by Gerard Grisey), here performed live with a thrilling pairing of individual dancers and instrumentalists. Sydney Chamber Opera’s Passion, by Marcel Dusapin, was another festival great (see below), an intense psychological journey into a dark place. The same company’s O Mensch, again from Dusapin, a solo about Nietschke in crisis played by the superb Sydney singer-actor Mitchell Riley was also a winner. Belgium’s Anima Eterna on period instruments reinvigorated my relationship with Beethoven’s 5th and 6th symphonies now rendered curiously modern.

Meow Meow reached new heights and production values with her spectacular Little Mermaid. I liked Woyzeck, not everyone did, so here I dip into the swirl of opinions. Virginia and I ranked the weird and wonderful The Object Lesson highly (see her review), as we did This Is How We Die, a visceral spoken word, anxiety-ridden fantasy by Canadian Christopher Brett Bailey (see Teik Kim Pok’s response). Another very frank expression of life’s complexities came from Norwegian singer-cum-performance artist Jenny Hval with a just as idiosyncratic accompanying dancer. Stephanie Lake’s dance work Double Blind had much to offer about social control if seeming thematically limited (see below).

Next week Angus McPherson will review the contemporary music event Exit Ceremonies and I’ll address FASE and Vortex Temporum; the wonderful local production In Between 2, about family history and two young men growing into maturity and art as Asian Australians; O Mensch; the very strange Japanese-Peruvian +51 Aviacion, San Borja; and two problematic productions, The Events and Cut the Sky. By then my own overall impressions of the festival will, I hope, have taken shape. In the meantime I’ve felt thrilled and challenged, work by work.

Elise Caluwaerts, Wiard Witholt, Passion, Sydney Festival

photo Jamie Williams

Elise Caluwaerts, Wiard Witholt, Passion, Sydney Festival

Sydney Chamber Opera, Passion

If you’d ever experienced the coming apart of a relationship without ever understanding precisely why it unravelled, why certain words were never spoken, those uttered were misunderstood and how couples become either invisible—or too visible—to each other, then leading French composer Pascal Dusapin’s chamber opera Passion would have made a lot of sense to you. It did to me, even though his approach is rarely literal. But with its superabundance of feeling it was never abstract.

True to its title, Passion is emotionally intense and embracingly lyrical (no hard-edged, angular modernism here). Before a dimly lit instrumental ensemble and chorus, a pair of lovers (Wiard Witholt and Elise Caluwaerts), physically oblivious to each other and their emotional ties weakened, wander a desolate landscape of low, erect shards of broken glass on the forestage.

Modest compared with other Sydney Chamber Opera productions, the design of this production (imported by SCO and the Sydney Festival, but with local conductor, musicians and chorus) provides a tight focus on the singers as they circle, evade and finally draw close, at the very moment they are irredeemably separated. Emphatic sighs, raw cries, snatched breaths and gasps, clapping, the soprano’s octave leaps and the baritone’s falsetto intensify the sense of passion—his love for her and her desire for death.

Dusapin’s inspiration is in part Monteverdi’s Orfeo et Euridice (most palpable in a delicately spare solo harpsichord passage (Zubin Kanga) but the separation of these lovers is of a different kind, of lives grown apart, with one sinking into profound depression. Both experience the absence of the Sun (symbolic of their love and what their lives might have been). Feeling neither understood nor cared for by her lover—“To you I am only an apparition”— she is in the throes of a death wish. He can’t grasp why nor can she offer any reason, save for the gnomic “Don’t you know? There, everything meets its opposite.” Nevertheless he is tempted to venture with her into an underworld powerfully realised by the work’s surround sound electronic score.

The libretto by Dusapin and Rita de Letteriis is elliptical, cyclically repetitive, sparely imagistic, heightening the music’s sense of nightmarish reverie. Shakuhachi-imbued flute (Jane Duncan) and a harp and harpsichord accompanied oud solo (James Wannnan) intensify the sense of sheer otherness that pervades this work—the outer reaches to which passion takes lovers, happy or not—the man can only guess at what possesses his beloved, “the beast that makes you scream, that allows no one to approach it.”

The singers’ powerful vocal and dramatic performances are entirely at one, the enigmatic chorus of six (The Others) underlines and complicates our feelings for the protagonists and the instrumental ensemble, conducted by Jack Symonds, realises Dusapin’s score (available on YouTube) with subtlety and seductive fluency.

Pierre Audi’s “mis-en-space” (which is how his direction is credited) is essentially a series of tableaux, but within these are varying degrees of movement and highly nuanced performances. I now yearn to see the work on the larger scale realised by Dusapin and the Sasha Waltz dance company in Paris in 2010 with the remarkable Canadian soprano Barbara Hannigan, who dances in the production, and baritone Georg Nigl. I suspect, or at least hope, it might make more sense of the role of The Others and of the stage directions (in the program provided to the audience) for the final moments of the work: “The heavens open up…” and “By now, all that can be seen is a mouth singing.” This SCO co-production, made in Australia from imported ingredients, proved an engrossing introduction to a significant work from a composer little known here.

Woyzeck, Sydney Festival

photo Jamie Williams

Woyzeck, Sydney Festival

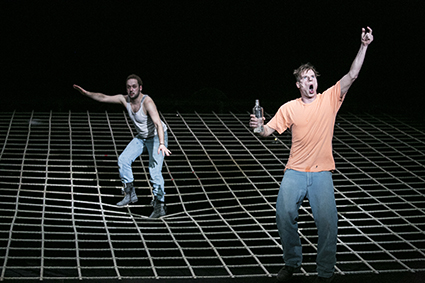

Thalia Theater Hamburg, Woyzeck

Among reviewers and friends I seem to be one of the few to enjoy Jette Steckel’s music theatre production of Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck (1837) as adapted by Robert Wilson, Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan (2000). The set design irritated many: it was “all metaphor,” “too cumbersome,” “slowed the pace,” “too obvious.” It comprised a vast mobile net in which the characters found themselves trapped or in a place to unleash their passions and cruelties and from which they would from time to time ‘escape’ to the forestage. Steckel consistently worked Florian Lösche’s net, strategising the various ways the characters engaged with it—feet falling though the grid or walking smoothly when drunk (Andres), bouncing with joy or sheer frustration (Marie) or, in the final scene, the murdered Marie is lowered through it by Woyzeck into the liquid depths where he will join her. I thought the net a pretty good metaphor, as did Thea Breizek, Professor for Spatial Theory, University of Technology Sydney, in The Conversation: “[It] reminds us that the social safety net we have come to be accustomed to since the welfare reforms of the late 19th century only carries some, and inevitably lets others fall. Quite literally, there’s no use hanging on. Lösche’s net may seem a simple, single message by director Jette Steckel, yet it is a highly effective one, demanding of the actors a highly physical language of climbing, hanging on and falling.”

The safety net fits nicely too with Tom Waits’ circusy music and the overall intense physicality of the production, as in the violent encounter between Woyzeck and the Drum Major played out over a thumped large bass drum. One complainant thought the production’s overall movement poorly choreographed. Not that I saw. I was specifically impressed with certain scenes, such as one with the Doctor’s strange, staccato dance, a kind of malfunctioning similar to the Captain’s repeatedly shooting himself in the foot, underlining the weaknesses of those in power.

There were objections that Marie, the increasingly estranged wife of Woyzeck, was portrayed as the trigger for rather than victim of domestic violence, or, alternatively, was treated with unusual sympathy. She certainly feels bad, expressing anger at herself in song and pressing herself violently into the net. A particular oddity was the appearance of the Drum Major—scruffy, in a long coat and lacking any obvious appeal, military or otherwise, with which to attract a Marie desperate to improve her lot. A misstep?

In a similar vein, a recurrent complaint was about the absence of ‘character development.’ Well, it’s not that kind of play, although it still requires a certain consistency. A precursor to 20th century expressionist drama, it’s a series of 37 fragments—cut, pasted and deleted according to the interpretations of generations of directors—and without an ending (Woyzeck’s drowning a suspected possibility). The bluntness, the unexpected and the disjunctions in Woyzeck constitute its power. For example, when Marie changes tack or as we witness Woyzeck himself transform episodically from naïve philosopher with political insights—how can the poor afford morality without money; “everything under the sun is work…we sweat in our sleep”—to become prophet of a fiery apocalypse and revealing the dark emptiness beneath our lives. Juxtaposed hard up against his vision are the cynics, who can afford to be so: the Captain, the Doctor and the Drum Major who all humiliate and abuse him. None of this is subtle, but it is powerful and as much precursor to Brecht as to Expressionism.

As for the music, some enjoyed it but felt a disjuncture between English lyrics and German dialogue. Others found the music to be aptly in the Weill-Dessau tradition, a good fit with the production’s Brechtian impulses. I had to agree with those who thought some songs too heavily rendered in the guttural Waits manner (they’re ofter in the composer’s own versions on the Blood Money CD). However, among more lucid responses, Julian Greis as Karl, an idiot, delivered “Starving in the belly of a whale” with a beautiful, slightly off-centre delicacy. The orchestration, conducted by Laurenz Wannenmacher, added new complexity to the Waits-Brennan songs.

Performances were strong and characterful. I especially liked Felix Knopp’s Woyzeck, strong, intense, bewildered and crazed.

One reviewer concluded about the production, “It all felt a little like school and no matter the work’s artistic integrity and heft, I doubt much of the audience connected deeply with it… The work wasn’t made for Australian audiences, and it shows.”

I’d never want a work of art made for me in that sense, let alone in terms of national culture. I want art to make me. As for calibre of Thalia’s production, Woyzeck is one of those plays that many of us have an ideal version of in our heads, even if we’ve yet to see it.

Meow Meow, The Little Mermaid, Sydney Festival

photo Prudence Upton

Meow Meow, The Little Mermaid, Sydney Festival

Meow Meow’s The Little Mermaid

Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid is a nasty piece of work, cruel to the bitter end. The mermaid sacrifices her tail for legs with which to dance and for a soul so she can marry a prince. The bargain? Legs, yes, but with both the pain of dancing on knives and the loss of her tongue. She loses the prince to a girl whom he thinks saved him from drowning in a storm (it was the mermaid). She can save herself by killing the prince, but love wins out. Instead she drowns herself and, as foam and bubbles, rises to a higher realm where she might gain a soul should she do good deeds for humans for 300 years (sentence later reduced by the writer, after complaints, to a year off for each good deed, or more days for bad). What a deal. Borders are not made to be crossed, little girls.

Of course I wasn’t expecting Meow Meow in her own The Little Mermaid to wallow in the tale’s murky shallows; hers is another kind of miserabilism, a jolly self-parodic one for the lovelorn or the would-be-loved whose narcissism inhibits romantic coupling. But the tale is there, as well as I can recall. There’s a storm, a transformation—first Meow Meow becomes the mermaid but wrong way up, tail on head. We help her get it off. Then, after a search (Meow Meow brave as ever crowd-surfing over the heads of her enabling audience) her prince appears, a desirable Aussie technician who interrupts the show and whose legs are spotlit and admired as he rises into the rig. She saves him, but sex is hilariously impossible with a tail and he shoots through (“I’m more of a leg man”) to another job. Subsequently, with a fearsome scream, our heroine gains legs, a glittering high heeled ‘slipper’ a la Cinderella on one foot, the other en pointe, plus crutch. The technician reappears as a grossly fantastical prince replete with sea-shell codpiece. She rejects him, preferring “a rock god or a ballet dancer.” Now the tale seems less mermaid and more Meow Meow as she learns, “I made my own fantasy reject me.” SPOILER ALERT Neither mermaid nor Meow Meow gets her man, but like her avatar, the artist nevertheless has her moment of transcendence with bubbles (the foam of the original tale) spectacularly filling the Spiegeltent. Even though her erstwhile techie prince exits in the end, she declares the show a “happy” one.

It’s also an action packed show with a spectacular set—a huge rising mirrored disk that becomes the sea at various depths)—and a superb band. The songs sounded pretty good, finely sung with the artist’s usual great range, though they’re largely less than familiar; a CD/download would be welcome, soon as.

Meow Meow was in superior form, the beloved familiar schtick upgraded with greater production values, strong direction (Michael Kantor) and a quite rewardingly complex tale. The techie is played by the very fine Chris Ryan, a perfect foil for Meow Meow, not only in their comic exchanges, but also for the intensity of their final encounter when it’s the techie’s prompting that pushes her into self-awareness. She might not have gained a prince, but she’s learned she’s adept at destroying relationships even before they get underway. At least she won’t be banished for 300 years awaiting soulhood; she is doing humankind too much good in the meantime. What tale next to hang her neuroses on?

Double Blind

photo Prudence Upton

Double Blind

Stephanie Lake, Double Blind

A man (Alisdair McIndoe) and a woman (Alana Everett), each trailing a long cable, face each other. Mere movement generates static, a touch to the cheek a buzz. At first the pair are tentatively intimate, sometimes funny (she cups his ‘breasts,’ each yielding a cute sonic zing), but with a potential for testing limits of more forceful proximity. The limit is reached. They collapse but then recommence, this time with probes in hand with which to stroke and jab, yielding more powerful sounds and physical effects.

Stephanie Lake’s Double Blind is about the consequences of experiments in which power is exercised with ignorance, diminishing caution and increasing abandon. Shocks, falls and immobilisations multiply across the performance as limits are reached with no sign of concern or mutual support. These ‘experimental’ results are at once banal, funny and frightening, recalling not only Stanley Milgram’s behaviourist research of the 60s, with the apparent application of escalating electric shocks to subjects by volunteers willingly following directions, but also a plethora of technological and ideological contemporary developments that are reducing our sense of ourselves as possessed of voluntary capacities. As Double Blind progresses, collapse is preceded by twitches, wobbles and spasms, with increasing signs of involuntarism.

The cables emanate from a platform on which sits composer Robin Fox like a master experimenter, neutrally monitoring progress and tweaking volume and electrical charges.

The dancers variously become the conductors and subjects of these experiments (neither party informed of the precise nature of the experiment—hence ‘double blind’). One briefly becomes the choreographer, since Lake includes choreographers among her dangerous experimenters. Consequently there’s an oscillation between scenes palpably about science and technological effects and those which are dance-centred, but still resonate with the former. For example, Everett and McIndoe’s second encounter climaxes when Everett ‘hits’ McIndoe—a gunshot knock with the probe that fells him; it’s comic, but a shock nonetheless. In the next scene, Amber Haines and Kyle Page join Everett and McIndoe to perform an increasingly elaborate baroque-cum-folk dance—Riverdance-like footwork and neat gesturing—that transforms into rapid turns and jumps with a driven quality suggesting something more than volition at work. This is the first of a series of scenes in which dancers are pushed into feverish, often mechanistic movement that nonetheless and quite ironically reveals sheer skill in its realisation. Here it’s propelled by an emphatic beat, textured with cooler sonic drips and then sharp clapping which turns disturbingly asynchronous, stops and starts again in counterpoint to the tight choreography.

Seated on the floor, McIndoe, in another ‘dance’ scene, comes under the sway of Amber Haines standing over him, as if manipulated first by her movement and then by touch until there’s a strange merger in which her forearm appears to become part of his head; all the while radio-like signals sustain a sense of laboratory but also of an older magic, of psychic control, played out here in an eerie, dim blue-ish light. The outcome is rise, fall, rise and finally collapse for McIndoe.

Double Blind takes a more literal turn with the playing of recordings of mid-20th century behavioural scientists describing experiments in which animals compete for food and sated ones become less competitive. While analysing behaviour these scientists were also proposing ways to manipulate it (which they did, egregiously, with chimpanzees and later children). Lake’s choreography, with the return of the spooky clapping motif, responds laterally to behaviourism’s cause-and-effect mentality with the foursome engaged in chains of action and reaction, mechanistic but sometimes beautiful and funny (nose to nose triggers), but showing signs of wobbliness and finishing with blunt impact and, again, collapse.

Double Blind

photo Prudence Upton

Double Blind

In another scene, McIndoe turns the sonic probe from the work’s opening on the other three in a dance of increasingly brutal impacts in synch with violent sounds. His dangerous loss of control is followed by Haines and Page duetting in a seriously complex tangling of bodies, recalling McIndoe and Haines’ earlier encounter. It’s another ‘dance experiment,’ fascinating in itself but hard to meaningfully accommodate at this point of the work’s thematic progress. More to the point is Everett, who, substituting for the choreographer, quietly instructs McIndoe in a series of complex movements. She then sets a metronome at increasing speeds until his performance becomes almost impossibly fast and the choreography no longer itself. McIndoe accomplishes the task, just. A bell signals the stages of this experiment while a clacking sound suggests a weaver’s shuttle (as antique as the metronome), recalling the earlier clapping and reminding us of the long gestation of technologies that act as prostheses and, ultimately, our replacements.

In a variation on the earlier cause-and-effect dance the four gather in movement which first appears unusually sinuous, cyclic and organic—bodies rippling in synch and arms snaking in line; but spasmodic movements suggest imminent entropy. In another return to the opening scene, the women wheel on an electrical system and attach the probes to various parts of the men’s bodies, increasingly disabling them. Oddly, in the opening performance, no sounds issued forth from these contacts, the impact being entirely visual. A technical problem or were the correlative amplifications of impacts no longer felt necessary?

In a final gathering in hazy light and amid the sounds of a big pulsing bass drum, static, water sounds, ship’s bell and distant voices—a curiously literal evocation—each dancer, feet forward and in parallel, moves with the others semi-robotically until clustering, their arms rave waving, as if trapped by both science and culture. Alone, Amber Haines, deprived of group togetherness, lyrically expresses isolation in movement riddled with spasms as the grid suspended above her kicks into life, a machine that casts large spotlight pools that rapidly circle the stage, oblivious to the artist.

Double Blind is an almost unremittingly grim evocation of the evils of mindless manipulation in the name of science—and of art. Stephanie Lake demands of her dancers high speed, sharply articulated virtuosity in a scenario with nil room for reflection with which to counter the entropy she envisages for our species. She’s created a work in which art is part of the problem—if sometimes, as with the metronome scene, portrayed ironically, but elsewhere with cruel intensity.

Lake has us dancing fast to our ethical and social extinction—a reminder that, analogously, our universe is also accelerating to its end. For all its taut, dextrously realised choreography and finely integrated complementary score (Robin Fox), Double Blind’s alternations between science and dance ‘experiments’ feel too schematic, becoming episodic and the overall sense of entropy predictable. I’ll remember its moments of dark beauty and many of sheer skill (McIndoe’s above all) that suggest the work has more to offer than protesting a condition evolving from the mid 20th century. Just what its manifestations are now, the exacting freneticism of some modern dance aside, is left to the audience.

With its involuntary and mechanistic behaviours Double Blind makes an interesting companion piece for Garry Stewart’s Devolution (2006) and Be Your Self (2012; video interview), both for ADT. Human ‘de-evolution’ is realised in the form of feral humans, some of whom have become whip-tailed cyborgs, while in Be Your Self involuntary behaviour consumes its humans before they appear to make a return to nature.

–

Sydney Festival & Sydney Chamber Opera, The Passion, composer, librettist Pascal Dusapin, librettist Rita de Letteriis, mis-en-space Pierre Audi, conductor Jack Symonds; City Recital Hall, Sydney 14-15 Jan

Sydney Festival, Thalia Theater Hamburg, Woyzeck, writer Georg Büchner, adaptation Tom Waits, Kathleen Brennan, Robert Wilson, director Jette Steckel, design Florain Lösche; Carriageworks, 7-12 Jan

Malthouse & Sydney Festival, Meow Meow’s The Little Mermaid, creator, performer Meow Meow with Chris Ryan and The Siren Effect Orchestra, director, Michael Kantor, design Anna Cordingley, lighting Paul Jackson, musical direction Jethro Woodward, comedy direction Cal McCrystal; Magic Mirrors Spiegeltent, 7-23 Jan

Sydney Festival, Double Blind, choreographer Stephanie Lake, composer Robin Fox, lighting Bosco Shaw, costumes Harriet Oxley; Carriageworks, Sydney, 9-24 Jan