The woman, home alone

Rachel Fensham

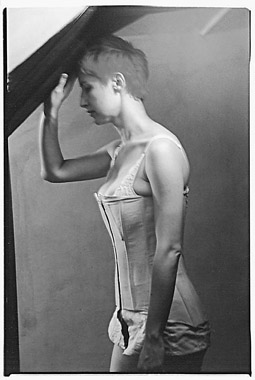

Roberta Bosetti, Room of Evidence

photo Georgia Wouffef

Roberta Bosetti, Room of Evidence

Obsession, catastrophe, haunting—contemporary dramaturgy turns on an event which subverts the system of things. A rupture in which the contours of the incident—its wave frequency—replay interminably without repetition. This is not merely a psychological condition but the inverted theatricality of social disaster.

The Secret Room project of Cuoccolo/Bosetti risks representing the catastrophe of the female subject and her disastrous existence. Its recent production Room of Evidence is the prequel for the successful and prolonged season of The Secret Room (RT40 p12), a dinner party performance of confessions. A prologue has however its own dramaturgy. We meet the characters, locate the settings, hear of the subplots and likely scenarios. It is also an event.

Room of Evidence begins with a journey through the city in a mini-bus. An enigmatic driver takes a small group of 8 through streets that he resites in the realms of history or myth. Here is where a grandmother gave birth to 12 children; over there is where the flooded river turned back the army. And through a lighted window in a charming Carlton cottage we can see where the hero spurned his young mistress. On one night, this was the room in which a woman on the bus watched her unsuspecting boyfriend in front of the television. This is the mise-en-scène of discovery, the mapping of unsuspected territory.

Then there is the arrival—an empty house, the CD player, a nature documentary on television, books and other personal possessions scattered around the different rooms. It is a modern house, white and sterile—objects have not quite found their home. The adventurous ones proceed upstairs to survey the horizon. OOPS—there is a shower running! Someone is in the house!

The emergence of the woman is primal. She of the white bathrobe, the image of Psycho interrupted. “Who are you? What are you doing in my house?” she demands. Invasion, violation, threat—we are all guilty. This event re-enacts the violent meeting of viewer and subject. Over the next long while, we negotiate our relations as audience to her, the female actor performing the woman at home. She is beautiful, tense, provoked and yet, gracious. She accommodates our awkwardness.

There are 3 more stages—the room where she shows us the family album, the photos, the old school books, the scrawled letters, the coded messages from an older man to a woman he has shamed. The script is already written. The performer Roberta Bosetti is strangely detached through this scene. As a moment in dialogue with the audience however it opens up collective associations with childhood.

Then there is the room with the bed. My favourite part of this more private encounter is the bicycle wheel whose dynamo revs up an illuminated Madonna. It recalls my first night in Italy when my boyfriend and I were given refuge in a church hall that we shared with a similar icon through the night. Even without this personal memory, there is something peculiarly ironic about the sexual pulse of a young girl being relayed through the luminosity of the Holy Virgin. But this is not a room of sweetness but of disclosure. Particularly for my group: very tentative, incomplete and a little embarrassing. There is too much left unsaid, but then that happens too.

The final scene of parting occurs in a room of paired shoes. Here the woman can try on her outside personas. There are many possibilities. She will escort us to the door and wave good-bye. She looks wistful.

Director Renato Cuoccolo talks of this project as a new theatre, where the boundaries of life and art are blurred. Can you imagine having a performance with a small but paying audience in your home every night? And he also talks of the precision with which different audiences reproduce their response to the drama of a woman alone. By crushing perspective, we are implicated in the figure of Bosetti as the feminine, whether lover, muse or enigma. The project reminds me of Ingmar Bergman and his relationship with Liv Ullman—there is the same intimacy of observation, the same stuttered telling and the same tension of suspended desire. It is as if the theatre has become simultaneously cinematic and unconscionably personal. And our role in the woman’s story remains an open question, to be further tested as The Secret Room becomes a trilogy later this year.

Room of Evidence, director Renato Cuoccolo, performer Roberta Bosetti, secret address, Carlton, Melbourne, opened Nov 12, 2001

RealTime issue #47 Feb-March 2002 pg. 36