To live, dance and love, with HIV

Andrew Fuhrmann: Jacob Boehme, Blood on the Dance Floor

Jacob Boehme, Blood on the Dance Floor

Over the last decade and a half, life has changed considerably for people living with HIV. Consider this passage from John Foster’s celebrated memoir, Take Me to Paris, Johnny, first published in 1993 but recently re-released, about the death of his lover Juan Céspedes:

“The virus makes you obsessive. It settles in your head. It distorts your vision. In the first flood of knowing—or believing—it can make you regard your own body with horror. The blood that is in you is lethal. It could drive you crazy if you dwelt on that knowledge, if you said to yourself, ‘I am the embodiment of death.'”

Now picture Jacob Boehme, an HIV-positive Melbourne-based artist, glamming it up in a billowy turquoise kimono jacket with deep sleeves, smoking a cigarette, teasing the audience and reminiscing about life and death at the height of the AIDS crisis in Sydney.

It’s a prologue to the main event, and the humour is very camp and more than a little facetious, with exaggerated descriptions of doomed drag queens lingering over their final bows.

Apart from lightening the mood, what is Boehme doing with this brief introduction? Is he really parodying narratives of emaciation and death? In any case, it’s clear he has a different story to tell.

Boehme, 24 in 1998 when he contracted the disease, is part of a generation for whom ‘positive’ is not a death sentence. Today, life expectancies for young people living with HIV are almost normal. For a man like Boehme, the struggle is not so much with the enemy in his blood—which can be managed with pills—but with the persistent stigma associated with infection, particularly in the male gay community.

Jacob Boehme, Blood on the Dance Floor

And so—Blood on the Dance Floor, a moving and highly polished one-man show presented by Ilbijerri Theatre. Deftly directed by Isaac Drandic, the piece combines dance interludes choreographed by Mariaa Randall with a well-composed series of autobiographical vignettes by Boehme.

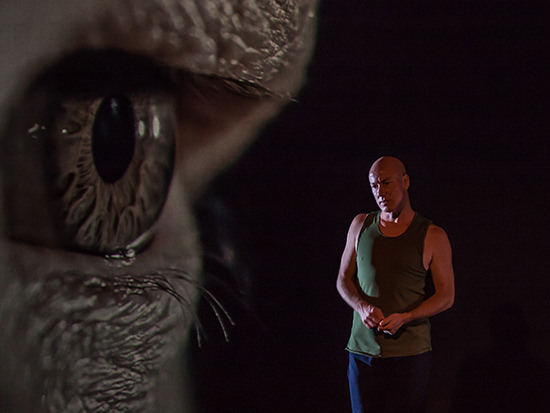

The show’s central conceit is simple enough: Boehme has a date. Wearing singlet and slacks, he paces nervously from one end of the stage to the other. He tells us that he’s terrified. He’s been seeing this man for a while, and everything is going well, but now it’s time to have the conversation. Boehme plans to reveal his most intimate secret—and it’s not that he buys his washing detergent at Aldi.

A second narrative strand engages Boehme’s Aboriginal heritage. He acts out a series of touching conversations with his dying father about the importance of family and the perils of loneliness. In both stories, with father and with lover, the fear of rejection looms large.

Throughout, Randall’s choreography emphasises Boehme’s compact, muscular build. During one passage Boehme—who attended NAISDA with Randall—performs in silhouette against a white background, moving slowly but nimbly through a succession of athletic poses. Later he appears to be performing against a video recording of blood viewed under a microscope. He moves in smooth almost languorous phrases, bending, crouching and extending, as if turned by the gentle current.

Some of the more delicate passages—for instance, repeated gestures where Boehme strokes the veins in his arm or flutters his fingers—can seem a bit awkward. But, overall, what we get is a visible index of his apparent health. This is not a man who regards his body with horror.

Jacob Boehme, Blood on the Dance Floor

The idea that potential lovers expect him to look sick is a recurring anxiety. In one scene, he describes a nightmare orgy in which everyone gets what he wants, except Boehme. A handsome stranger emerges from the shadows and they start making out. Boehme can smell the sex: he wants it raw. Everyone always wants it raw. But then, the inevitable question, “Are you clean?”

Behind him, projected onto the screen at the back of the stage, we see—in devastating high-definition–a close-up video of naked flesh. It’s as if Boehme is haunted by these night-time yearnings for the intimacy of skin on skin.

There are many large issues at play in Blood on the Dance Floor, but the work’s emotional pulse is in the ordinariness of Boehme’s need for love and for a sense of belonging. Thanks to modern regimens, he has a future against which he can balance the present: he can dream, and his dreams might one day be reality. And yet he remains understandably sensitive to the attitudes of those around him. The history—and the myth—of the “gay plague” is a constant burden.

But it’s history that makes Blood on the Dance Floor such an affecting piece of theatre; and it’s the implicit contrast with Juan Céspedes, who was also a dancer and who died in 1987, that gives poignant substance to Boehme’s story, and to the apparent banality of his desires.

At last, Boehme is ready to meet his lover. He faces the audience and somehow seems to step out of the performance. Here we feel the full effect of his sincerity. “My name is Jacob Boehme,” he says. “I’m Aboriginal. I’m HIV-positive. I buy my laundry detergent from Aldi. And I’m in love.”

–

Ilbijerri Theatre Company & Jacob Boehme, Blood on the Dance Floor, writer, performer Jacob Boehme, director Isaac Drandic, choreographer Mariaa Randall, video artist Keith Deverell, sound designer James Henry; Arts House, North Melbourne, 1-5 June

RealTime issue #133 June-July 2016