transgression, translation, transcription

keith gallasch: ruark lewis interview

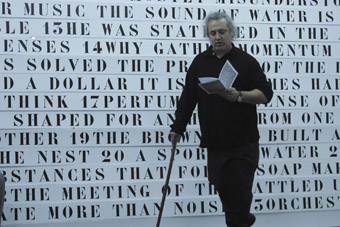

Ruark Lewis, A Babel Reading-Machine (2005)

photo William Yang

Ruark Lewis, A Babel Reading-Machine (2005)

RUARK LEWIS IS A PASSIONATELY POLITICAL AND COLLABORATIVE ARTIST WORKING ACROSS AND INTEGRATING PAINTING, DRAWING, INSTALLATION, ARTIST BOOKS, PUBLIC ART, PERFORMANCES, AUDIO AND VIDEO WORKS. HIS METHOD, WHICH HE TITLES “TRANSCRIPTION (DRAWING)”, OFTEN TAKES THE WORK OF OTHER ARTISTS—COMPOSERS, POETS, CHOREOGRAPHERS, ANTHROPOLOGISTS AND FELLOW VISUAL ARTISTS—AND TRANSFORMS IT INTO ABSTRACTED TEXT EMBODIED IN IMMACULATE SCULPTURAL INSTALLATIONS IN A RANGE OF MATERIALS INCLUDING CLOTH, TIMBER AND STONE, OR TRANSPOSED ONTO THE FACES OF BUILDINGS, AS IN RECENT PUBLIC ART WORKS. THIS ARTICLE REPRESENTS A SMALL PART OF A FASCINATING CONVERSATION YOU CAN FIND AT WWW.REALTIMEARTS.NET.

Like a good poem, a Ruark Lewis work encourages contemplation and promises delayed revelation; then it’s art that stays with you. The man himself is more immediately accessible, an ubiquitous and energetic arts presence (despite a taxing physical disability) and an eager conversationalist—one for whom conversation, he says, is the source of much of his art, building on the images that first occur to him and take flight through talk and are then realised often in collaboration.

A long conversation with Ruark Lewis is a rich journey into cultural history from the 1980s on, of which his own career is a fascinating part. After studying ceramics, Lewis turned to curating public events for four years for the Art Gallery of New South Wales in the late 1980s. The resulting programs brought together a wide range of artists in performative mode. Doubtless, these telling juxtapositions and potentials for partnerships inspired the conversations which became his own collaborative art in the 1990s and up to the present. He created RAFT, a major work with Paul Carter for the Art Gallery of New South Wales and other commissioned works—for the 2000 Sydney Olympics, 2006 Biennale of Sydney and Performance Space. He collaborated with Jonathan Jones on an installation called An Index of Kindness at Post-Museum in Singapore 2007. His recent outdoor installations and sound works in the City of Sydney focus on the consequences of urban development. In October this year he travels to Canada where he’ll create a commissioned public art installation called Euphemisms for the Intimate Enemy for Toronto’s Nuit Blanche festival.

the public house

I asked Lewis about his City of Sydney project, which has recently taken him to Millers Point with its small remaining population of an older community residing amidst new developments and the palpable wealth of new apartment dwellers in the Rocks and Walsh Bay. He describes it as “a public artwork, which includes agit-prop elements, working with a group of people, studying the area and trying to develop a spoken word archive piece, an archive of community comment about lifestyle in the area at this time to do with ‘the public house.’ I’m looking at the ways that development encroaches upon traditional communities living in the inner city areas.” Lewis sees Sydney as having been through several visionary planning periods and with “a remarkable political history when you look at what the BLF forged with the Green Bans…It’s a history of significant counterpoints between the dissident voice, the resistant voice and the government and the developers.” The words of the community, material for Lewis’ text, are being found at the Darling Harbour branch of the ALP and the National Trust and Tenant’s Union.

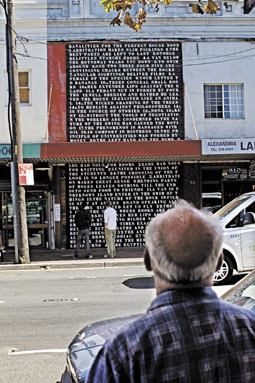

Banalaties for the Perfect House installation, Slot Gallery

photo Alex Wisser

Banalaties for the Perfect House installation, Slot Gallery

Lewis is keen “to make an environmentally integrated artwork. That’s how we worked at Homebush on public art at the Olympic site, making Relay with Paul Carter’s text during 1999-2000 as a Sydney Olympic Games commission. There are no spaces between words and I designed a colour code to cross-reference through the ongoing sequences of five rising stone steps. We had three kilometres of texting going up and down those stone bleachers. The planners were very keen to create a public art that would environmentally integrate with both the site and the sporting events and audience. They didn’t want decorative art baubles. I thought that was a workable approach for an ongoing strategy for placing works in the public zone…I’m still working on that idea and trying to find ways of lightly integrating installed works into the actual building fabric. I’ve done it on couple of locations recently. At an artist-run-initiative called SLOT in Regent Street Redfern I made a seven-metre high façade on the front of the building using the width of the shopfront downstairs and closing off the apartment windows upstairs and taking the text all the way to the parapet. It’s a peoples’ poem called Banalities for the Perfect House.”

We watched and spoke to a lot of people in the street in Redfern to see what their reactions were. A grandmother was drunk in the street and she had tears in her eyes as she stared across the road. “What’s this? What’s this?”, she kept crying. I asked her what the matter was and she replied, “I’ve got to explain this to my grandchildren because when I come up here shopping with them they’re gonna ask about it.” So I said “maybe it’s poetry.” She said, “I know it’s fucking poetry! But what does it mean?” I said, “I’m not quite sure what it means.” She said, “Ah! come on it’s not that complicated.”

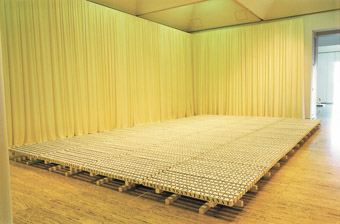

An index of Kindness, Chalk Horse Gallery, Sydney, 2008

courtesy the artist

An index of Kindness, Chalk Horse Gallery, Sydney, 2008

municipal signs & other objects

Lewis’ most recent show, at Chalk Horse in Sydney’s Surry Hills, draws on work from his shared show with Jonathan Jones at Singapore’s Post-Museum. The gallery was hung with flags stencilled with words from Nathalie Sarraute’s play SILENCE. Below, on the floor and plinths, everyday found objects had been painted with red, black and white stripes and markings, making the gallery-goer doubly attentive—to where they trod and how they were regarding the art. Lewis surmises that he’s using the gallery to test out some of his outdoor optical and spatial systems: “I’ve been considering the sculptural objects in the show as decoys. They’re like the rocks of Mer in the Torres Strait. Eddie Mabo identified a bunch of rocks around his Island of Mer as being the markers for the language or community zones. I thought that’s a very useful message for all Australians to start to recognise…”

In Singapore, says Lewis, “I was actually looking for garbage. I thought, here’s a place where you can’t have long hair, you can’t chew gum, what can you do? So I started making work about the garbage—on the streets, in the countryside or washed up on the beach…I stencilled messages onto pieces of garbage.” Then he placed the garbage back where he found it and made a photographic record: “This formed an intimate poetic puzzle. I wanted to leave messages for people anonymously. I avoided the fear of arrest by photographing the evidence before and after I removed it. Sometimes I kept elements of the garbage to paint an abstract pattern on it—with red and white or black and white stripes painted in gouache.”

the artist begins

We step back in time to Lewis’ beginnings as an artist. He went to Sydney Boys High School where “One day I went up to the art room and a friend of mine was throwing on the pottery wheel. I became totally mesmerised how that form came up out of his hands and fingers. I loved the slithering plastic action of the clay that formed in his hands. I went straight out and bought a bag of clay that afternoon and made a sculpture, not a pot as such.” With a photographer brother and musician and painter cousins, Lewis describes himself as “sort of coming from a Jewish artistic family—a tribe of mercantiles and artists. According to the painter Cedric Emmanuel our earliest Australian relative was Michael Michaels. He was a forger who was pardoned in 1809 and left Sydney returning to London and he started an orchestra. We’ve always had painters and musicians in the family so making things seems natural to us.”

Lewis studied Ceramics at the Sydney College of the Arts: “It was difficult for me physically but I needed the tangibility of clay.” But a major influence there opposed his interest in ceramics: “the composer David Ahern in the Sound department. David was a total radical. He’d been working with Cornelius Cardew in London and for two years was a personal assistant to Karlheinz Stockhausen. He came back to Sydney in the early 70s and among other things he ran a Sunday new music workshop out of Inhibodress Gallery. That was the group called Teletopia and AZ Music. Tim Johnson and Mike Parr and Peter Kennedy ran the avant-garde concept gallery the rest of the week. But on Sunday the experimental artists ran an open studio where trained and untrained musicians joined together to perform music. Although I wasn’t involved in those early years I’ve been very interested and was highly motivated and inspired by Ahern’s practice. It was wild. It was recklessly terrific. I thought this is really what art’s about. Because it was a language made of sound and music…Ahern was very discouraging of my interest in ceramics and always urged me to paint and draw.”

But, says Lewis, “Ceramics gave me a sort of classical education, which I may not otherwise have received in such a serious avant-garde art school.” An interest in architecture has also been “infinitely useful.” Such contrasting influences were to yield a seriously idiosyncratic artist. The sense of difference was compounded in 1984: “I was expelled from Sydney College of the Arts. That was pretty demeaning—it really wasn’t my fault. I also had been expelled from Sydney Boys High School in 1978. Perhaps both these rejections shore me up as a kind of outsider in art—in that I seemed able to miss out on certain unnecessary things exactly at the right time.”

the artist as curator

Lewis began first as a reader and then as a curator of poetry readings at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and then with Emmanuel Gasparinatos “who programmed a new media event in the theatrette called Sound Alibis with 14 artists including Rik Rue, Warren Burt, Sarah Hopkins and Vineta Lagzdina. There were Super 8 films and sound works and live performances. I developed the program further the next year with the poet and scholar Martin Harrison [who] was interested in the writer/performer as live presence…This began a really successful curatorial collaboration [becoming Writers in Recital]: it made the AGNSW the stage to a wide range of writers and musicians, composers, filmmakers, visual artists, performers dancers, radiophonic composers…I kept working out ideas of how to get the most radical types of experimental art out to the widest audience possible…even radio stations like 2GB would give me a five minute interview each season. I saw it as an act of anti-elitism to promote radical art to a willing public.” The big names, poets like Judith Wright, David Malouf or Les Murray, were programmed to attract large audiences who would witness, for example, “the soprano Elizabeth McGregor singing the Margaret Sutherland settings of early Judith Wright poems alongside the relatively unknown work of Allan Vizents, William Yang, Ania Walwicz or Jonathan Mills.”

escape to melbourne

After four years of curating, “in August 1990 I escaped Sydney. In Canberra I found a copy of TGH Strehlow’s Journey to Horseshoe Bend. It’s a biography/autobiography about the death of his father, the missioner Carl Strehlow in Central Australia in 1922. I started reading what turned out to be a transformative book for me.” It was important in developing Lewis’ art of “transcription” and “texting”, which would later lead to a major work with Paul Carter.

About the origins of his artistic process, Lewis explains, “I wanted to lay in poetic lines from poets I was reading at the time, like Rilke’s Duino Elegies. I wanted to actually enact it as a trace. At the time I was working on musical and sound transcriptions in the form of drawings. That’s how I’d begun texting into works and making abstract cross-overs from one art form to another.” He made diagrammatic drawings of sound works—acoustic music and then the work of the Sydney composer Robert Douglas who was making large-scale works on the Fairlight CMI.

my university

In Melbourne, Lewis spent time with Paul Carter, the director Peter King, Jonathan Mills, Warren Burt, Chris Mann, Vineta Lagzdina and Rainer Linz. The experimental music scene was particularly influential, coming out of the Clifton Hills Community Music Centre and the NMA magazine: “The Rainer Linz and John Jenkins’ 22 Australian Contemporary Composers anthology was the sort of curatorial guide I’d been looking for at AGNSW. There had been little like that sort of thing operating in Sydney…That was also the era of the ABC’s radio’s The Listening Room. Carter had been editing the Age Monthly Review which we’d all contributed to over the years. This was an artistic atmosphere I called ‘my university’.”

In Melbourne Grazia Gunn, director of ACCA offered Lewis a major solo exhibition opportunity which he worked on for two years. “I finished the Robert Douglas transcriptions, which ended up being 48 metres of extended drawing. The 48 panels occupied the Lotte Smorgon Room at the old ACCA in Melbourne’s Domain. There were studies of Douglas’ Homage to Bessemer. I made a room of literary transcriptions based on the French newspaper Le Monde. I’d been in Paris in 1991 and I found a way to look at the demarcations between the generating forces in commercial print media. It was a simple critique of how photography, journalism and advertising worked in concert on the pages and how that formed the capital which is the motivation for a daily publication.” The exhibition was part of Melbourne Festival in 1992: “Melbourne was into high postmodern and neo-expressionist painting then, and along comes an incredibly cool minimalist show with regional underscores. It was shown there for a lengthy 14 weeks.”

But the Melbourne show did not result in Lewis being immediately picked up elsewhere. He comments wryly, “I like the fact that you can work ‘fairly privately’ in Australia. I always understood that experimental art would be ignored by the local art cognoscenti and that the avant-garde was taken up by the academies that could easily canonise it in what I regard as a pseudo international context.”

the experimental realm

Lewis makes strong distinctions between the realms of the avant-garde and the experimental: “It was the expansiveness, I suppose, of the experimental realm, the idea that art and production could take on other forms in constant flux and I could rewrite them…” And there was a correspondence to this work outside of Australia for my artistic friends. John Cage had picked up on Chris Mann’s work and set it for an opera. What I find most interesting in writers like Mann and Walwicz is the certainty of their regional voice. [W]ith the experimental, there’s a sort of fraternity that I like, keen about reading through each other’s work, reading the sound waves that each artist arrives with.”

Lewis enjoyed this feeling when he met Kaye Mortley and René Farabet in Sydney: “Martin Harrison was a friend of Kaye’s. All sorts of interesting people came together at the Harrisons’ house. The dinners often went until dawn. When René and Kaye came to Australia a sort of sound circle developed around them and the Listening Room at the ABC and at UTS. René Farabet was director of the radiophonic atelier program called France Culture, so there were significant cross-overs with people working here. I went off to Paris in 1991 and had the best time of my life.” Lewis worked with Mortley on a rendering of the play Pour en Oui Pour en Non (Just for Nothing) by Nathalie Sarraute: “I immediately had a vision for setting the players’ script marked out on the page in different colours. The colour would navigate the reader through the text like a graphic score.”

RAFT (2005), with Paul Carter, collection Art Gallery NSW

photo Ian Hobbs

RAFT (2005), with Paul Carter, collection Art Gallery NSW

the raft journey

Asked about the genesis of RAFT, Lewis explains, “I often have visions of things—I see them in visual daydreams and then follow the image directly along into the work. I saw a large gridded structure that seemed to extend out along the surface, so I set off in that direction. The timber of RAFT weighs 1.5 tons. I started testing possible materials when I was staying in Melbourne in 1993. I later made three large Water Drawings which joined RAFT at the Art Gallery SA showing in 1997. Then our book, Dept of Translation, appeared in 2000 to coincide with the exhibit at the Sprengel Museum, Germany which occurred in 2001. So, only about seven years gestation. The Art Gallery of NSW where it was first exhibited acquired the work earlier this year.”

“We were looking at the Arrernte water myth of Kaporilja as the main poetic cross-reference for RAFT. RAFT symbolises the carriage that Carl Strehlow was transported down from Hermannsburg to Oodnadatta to get a train to Adelaide because of his fatal illness. But he died on the way, just north of Fink at Horseshoe Bend. RAFT has to do with issues of translation in the desert. It allegorically acts as a portrait of the classical intercultural brokering of the language scholar and evangelist missioner Carl Strehlow with his links to the first phase of modern anthropology. What’s so amazing is Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara performed various Arrernte and Lorritja songs at the Café Voltaire in May 1917…Three songs were performed, maybe with movement, and probably in the presence of James Joyce and maybe Lenin both of whom were resident in the neighbourhood. So, there’s the modernist trace again.”

the artist performs

I ask Lewis about the performative aspect of his work. In the exhibition at Chalk Horse there’s a beautiful recording of Amanda Stewart and Lewis doing something quite dramatic and very funny and largely unintelligible (but oddly familiar as social exchange) with occasional literal utterances. Lewis explains, “I have became increasingly interested in the process of concretising language and making a score I can follow and make performances from. Last year I asked Amanda” [whom he declares an inspiration] “to work on an improvisation that would in a non-representational way convey three emotions: anger, joy and sadness. As we huddled around a microphone in the studio we both began giggling, wondering how ridiculous we were, but a really intimate moment between artists emerged as we worked out a range of responses that we might record. Rik Rue collaged our efforts adding layers and depth and spatial elements which formed a kind of audio space poem at Post-Museum in Singapore in 2007. I called it An Index of Emotions. I think visitors were surprised and confronted by those spatial effects and some of the sobbing sounds and angry tones were quite distressing.”

Euphemisms for The Intimate Enemy

nuit blanche, toronto

Lewis’ work for Toronto’s Nuite Blanche (an all night, one night exhibition of 155 works across the city) is a sound installation called Euphemisms for The Intimate Enemy, with a duration of 12 hours . As with The Banalities of the Perfect House “the sound is computer generated but will be a live collage when the computer is started around 7pm on the night of the event. I’ve devised an installation of 550 oil drums to be stacked as a curtain wall between two 19th century industrial buildings. Each word of the Euphemisms is stencilled onto coloured (black and yellow) painted drums and will form an illuminated text in the void.”

See also full interview transcript.

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 50-51