Tribute to a pioneering dance media artist

Keith Gallasch: Stephen Jones, Dancing the music: Philippa Cullen 1950-75

Philippa Cullen, improvising, Australia 75, New Music Centre, Melbourne

In a lovingly curated exhibition, Stephen Jones resurrects the richly creative years, 1969-75, of the too short life of dancer and technological innovator Philippa Cullen whose aim, above all, was to free dancers from what she saw as the ‘tyranny’ of music by having them generate their own as they performed. The show exudes a potent sense of the late 1960s-early 1970s: years of protest, intensive collaboration, technological experimentation and enormous curiosity—a world the young video artist Jones was himself entering.

While the many posters, reviews, photographs, diagrams and the artist’s notebook drawings in the exhibition convey a palpable sense of the excitement of the period, the videos offer eerily fleeting visions of Cullen and her dancers in motion. I experience them as if ‘through a glass darkly.’ There’s a pervasive sense of mortality—of the loss of a pioneer whose work was not completed—and of a corresponding techno-archeological dig. Video ages and dies and the equipment that once played it is often lost. Thanks to unceasing commitment, Jones has digitised the video record and maintained the machines. Even if the figures in the images are frequently ghost-like and it’s not always easy to ascertain the precise shape of the dancing and its connection with the sounds generated, there’s so much to treasure here.

Philippa Cullen rehearsal Homage to Theremin II, NSW Conservatorium of Music 1972

Dance freed of music makes its own

The exhibition’s narrative reveals that a large number of innovative artists in Australia and beyond constellated around Cullen as she tirelessly built on the relationship established between dance and electronic devices initiated by Merce Cunningham and John Cage in 1965 in Cage’s Variations IV. Here dancers triggered signals via antennae or photo-electric cells when they interrupted light beams. Jones explains in the exhibition’s catalogue that the actual musical output in the Cage was still made by musicians (David Tudor and Gordon Mumma), whereas Cullen’s use of the theremin allowed her and her dancers to actually generate sound and her pairing of that instrument with the synthesizer was truly innovative. Cullen pushed beyond her peers, later adding pressure-sensitive floors and biofeedback to her systems to allow dancers the freedom she sought.

Philippa Cullen, Helen Herbertson, Sydney University Quadrangle, 1974

Dance: natural, communal, political

The rise of electronic music, computing and video art in this period corresponded with a new sense of freedom in dance. In America, Judson Church drew on everyday movement and improvisation, as did Cullen in Sydney, “highlighting the movement of natural activities.” She was fascinated with the sounds the body could make (slaps, claps, cries) when integrated with dance. Her preoccupation with dance as a communal activity led her, in 1968, to commence open workshops on Sunday afternoons in the University of Sydney Quadrangle (one image includes a young Helen Herbertson, subsequently a leading dance artist, performing with Cullen) and to create events on public transport and in city spaces including “confrontational” performances at the time of the Vietnam War. In a very clear recording by Melinda Brown in Martin Place in 1974 we witness Cullen and two dancer collaborators gently engaging with the public until a military band arrives, a wreath is laid and the trio stage a simple tableaux of opposition. The subsequent exchanges with the observant crowd are funny and fascinating in a recording that gives us the strongest sense of Cullen’s charismatic presence.

She also investigated communal dance, specifically on a trip to Ghana, where, she says she witnessed dance as “an act of rejoicing… participation, not performance.” She likewise saw the technological tools she was developing as potentially part of the public domain.

Philippa Cullen with wire loop antenna

Finding her way

The six years of Cullen’s explorations were busy with an astonishing number of critical discussions, experiments, collaborations, performances and events. Vision, determination, a capacity to find the right people and to make the most of fruitful chance encounters all drove the work forward despite the frustrations and failures that came from innovating with new tools and systems prone to breakdown.

The cultural intensity of these years, evident in posters and reviews and further detailed in Jones’ catalogue essay, is found in a rich litany of artists, computer scientists, technical engineers, venues, galleries, events and festivals. Cullen studied jazz and primitive dance from eight years of age at Bodenweiser Dance Studio where she performed in works by Jacqui Carroll, who later became a key collaborator. It seems that Cullen first found her niche at the University of Sydney Fine Arts Workshop (the highly influential Tin Sheds) in 1969-72 meeting artists and members of the experimental music scene, which included David Ahern’s AZ Music. At the Tin Sheds in 1969 she saw a theremin-based installation in which the audience “triggered sound and light patterns”. Cullen made a note that the electrical engineer on the project “wants to compose music for ballet.” She had also met Karlheinz Stockhausen when he visited Australia in 1970 (and would later spend time with him in Europe in discussion and performance). In Jilba Wallace’s 1976 documentary, A Life’s Work, Philippa Cullen, 1950-75, Jacqui Carroll describes Cullen as “initially, strictly a dancer,” but one with “a single-minded focus on experiment and process.”

Rehearsal, Homage to Theremin II

Dance with theremin

Cullen commenced work on performing with the theremin in collaboration with electrical engineer Phil Connor and technician and composer Greg Schiemer who connected the instrument with a VC3S audio synthesizer (courtesy of the University of Sydney’s Music Department), principally to yield better sound. Architecture student Manuel Nobleza designed an elegant set of theremin aerials. With dancers added, the group became Philippa Cullen’s Electronic Dance Ensemble. The work came to its fruition with Homage to Theremin II in 1972 (apparently a 1970 version, Electronic Aspects “was not particularly successful,” writes Jones) with four aerials and a photo-electric cell.

The stately, slender wire loop theremins, seen in the exhibition on video and in photographs (taken by Lillian Kristall), appear as simple exemplars of Modernist design and vehicles for human-scale interaction with technology. In one photo you can make out Cullen and Carroll with the loop aerials and, in the background, Schiemer, Connor and Nobleza. In another the two dancers are caught poised on the low pedestals, Carroll with arm raised high. On video we see Cullen and another dancer transitioning from supple arm movements to rapid, joyful bouncing, yielding corresponding sounds.

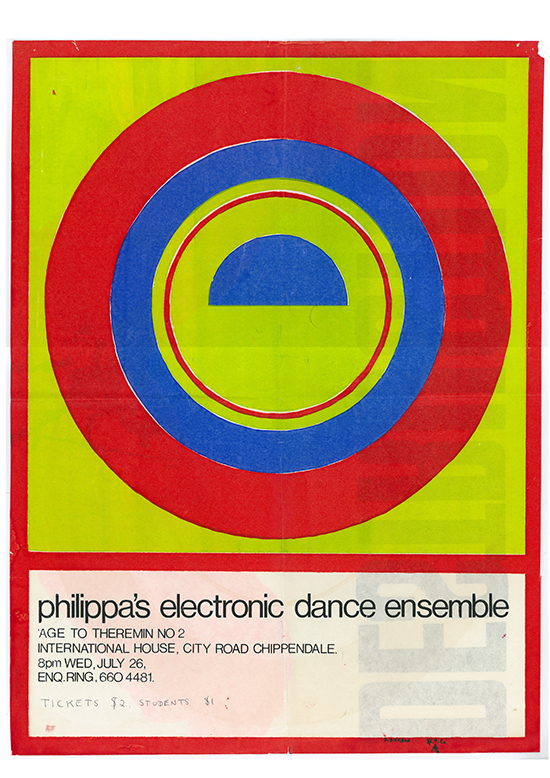

Poster, Philippa Cullen’s Homage to Theremin II

In 1972 Sydney Morning Herald reviewer Beth Dean wrote of Homage to Theremin II, “Jacqui Carroll took her place upon a circular pedestal base (aerial A). This created a quiet humming tone. As she slowly extended her arm upwards the pitch (frequency) [of the] sound rose louder and higher. The mood developed to an intensity of yearning. The fingers opened. She reached out, stretching both the sound and the body to taut heights of thinnest strain, she clenched her fist. The tone of audible sound and visual tension receded.”

Video images reveal Cullen, with two other dancers, rehearsing for Homage to Theremin II. She balances, one leg raised, arms shaped elegantly, hovering between stillness and the movement that will trigger sound. A tilt of the head, a sudden drop from the waist, the swing of an arm engender sounds ranging from long sustains and swooping glides to rounded whip-cracks. With arm extended slightly up, a reaching hand seems to touch a sweet sound. Another dancer joins Cullen on the small pedestal, the pair moving in and out of synch and sinking low to to generate a deep siren that becomes a growl. The trio moves about the theremins, unleashing staccato burblings, blips and zips. For a moment towards the end of the tape, a smiling Cullen suddenly comes into radiant focus.

Dancing experimental music

In the same period, Cullen continued to perform with musicians while also addressing sound, language and movement. Teletopa, an AZ Music-related electro-acoustic group, responded directly to her dancing. In an enthusiastic review in The Australian, in which she mocked conventional ballet, Maria Preauer (years later a vigorous opponent of innovation) wrote, “In some strange telepathic way [Cullen] became almost composer and conductor.”

Dancers given voice

Cullen expanded the engagement between voice and the dancing body in Utter (1972), a work for five dancers which, Jones tells us, was based on the sounds from the four languages spoken by writer George Alexander. It received a special mention in that year’s Ballet Australia Choreographic Competition. The video of Utter is not easy to interpret but the sounds heard are indicative as recalled in George Alexander’s account for Writings on Dance 4, 1988: “noises of unamplified voices, feet, hands, mantras, open chord droning, noisy yoga exhalations, gibberish, screams of rage, groans of agony, yesses of willing victims.” As for the movement, “Dancers were choreographed into amorphous turbulence, eating up gobs of audience or making carpet patterns of writhing bodies.” Stephen Jones confirms what is glimpsed on the video: Utter was “a free-wheeling radial performance centred on the cast of a spotlight on the centre of the stage.”

Cullen’s adventurousness was also evident in Lightless—at her most radical, comments Jones—a university lunchtime performance in a pitch black, carpeted room in which the dancers (identified only by different aromas) moved, according to dancer Patrick Harding-Irmer, among the scattered audience “rubbing up against bodies” and gradually removing layers of clothing. A very 70s performance but also related to Cullen’s interest in reaching out to “the threshholds of perception.”

Not merely bodies

Cullen says in Wallace’s documentary, “Dance in Australia has been too limited to those who want to learn it as a performance skill. The dancers are merely bodies used by the choreographer. This is unsatisfactory for an intermedia type of production. The performer must have an acute awareness of the media involved.” Many years later, Darren Tofts in “Cutting the new media umbilicus,” RealTime 27, Oct-Nov, 1998, argued for “intermedia” to replace “new media,” a term he regarded as redundant. “Intermedia” did not take on, but it’s fascinating that Cullen deploys the word at a time when hybridity in the arts was profoundly in the making.

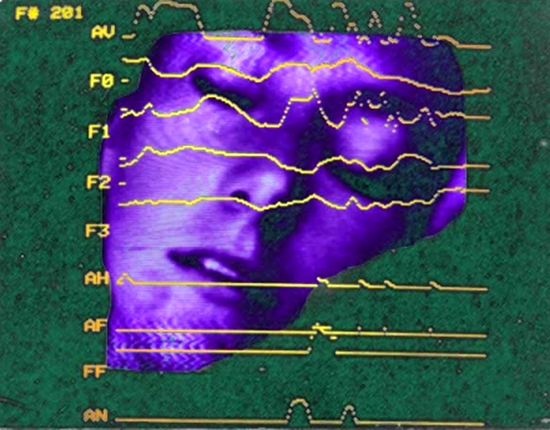

Philippa Cullen in composite with electromyogram, 1974

Europe, Ghana, India

A grant from the Australia Council in 1972 to explore “the medium of electronics and its potential for extending dance as an art form” took Cullen to Europe where she failed to find fellow explorers of interactive dance, but studied with Pina Bausch for a month and at The Institute of Sonology at Utrecht where she developed ideas for pressure sensitive floors (there’s a photograph of her tilting back on one) and investigated the potential of bio-sensors (seen in a colour image by Sydney artist Ariel of Cullen, eyes closed, with electromyogram readout made after her return). She worked with electronics at STEIM (Studio for Electro-Instrumental Music, Amsterdam, where Jacqui Carroll joined her), learning to become, out of sheer necessity, “a technical director,” visited Stockhausen, appearing in his Summer Nights Concerts, and spent three months in Ghana and then India “presenting workshops and learning Indian dance technique.” She saw India as the ideal place for bringing together the Ghanian sense of community and her work with technology within a cosmological dimension.

Back in Australia

In September 1974 Cullen presented 24 Hour Concert at Hogarth Gallery, Sydney, an event taped by Stephen Jones that involved dance (without electronics), a protracted chess game (Aleks Danko and Ian Robertson), cooking and the playing and deconstruction of an old upright piano by Chris Mann. The dancing also took place at the front of the Art Gallery of NSW and on the Domain and the train network.

Wayne Nichol, Philippa Cullen on pressure sensitive floors, Australia 75

Challenging times

Philippa Cullen continued her investigation into the possibilities of electronics and dance, presenting seminars and giving workshops and demonstrations of the findings of her travels. In 1975, she was invited to give workshops at the Computers Electronics in the Arts exhibition at the Australia 75 Festival of the Arts and Sciences (March, 1975) in Melbourne and to perform at the 6th Mildura Sculpture Triennial. Jones reports that she used the combined fee to buy a Synthi A (a portable version of the VCS3) to work with a set of pressure sensitive floors for Homage III. Computer failure, which meant that the dancers would not able to create sound, led to a chance encounter with two computer scientists who enabled movement on the floors to generate “computer images and video feedback.” There are impressionistic photographs of Cullen dressed in golden silk, her back to us, facing the bank of video monitors on which appear images of her dancing alone and with her company. Unfortunately I didn’t get to see the video recording of the performance, but I hope to do so.

Jones writes of the pace and generosity of the last-minute collaboration that “all this happened almost overnight and illustrates just how much interest there was in integrating all sorts of disparate systems as well as how willing everyone was to do everything possible to make the convergence work.” There were other challenging times, “a disastrous theremin breakdown.” Towards the end of his account, Jones reveals Cullen’s increasing feelings of frustration after the Australia 75 and Mildura events, one artist citing “a rapid falling out and shorter and shorter collaboration periods.”

On the thresholds of perception

However, she pushed on, developing pressure-sensitive floors. Noting the potential accessibility of her equipment for the public and “even children,” Cullen wrote, “The hard part is to program the synthesizer so that you are controlling a variable which is satisfying for the operator of the floors. And this is precisely the part of the system which is completely unknown to all but the initiated few. But I shall go on exploring the field because I am interested in the threshholds of perception.”

Although she spent some productive time with composers Vineta Lagzdina and Tristram Cary at Adelaide’s Elder Conservatorium in discussion and in workshops, including with ADT dancers, Jones writes that Cullen felt “somewhat alienated from computerised interactive work” and left for India where, sadly, she died on 25 July, 1975.

Before leaving, she had planned to work with friend and videomaker Melinda Brown in India on “a collaboration…which involved aspects of geology, astronomy and DNA—loosely working titled Dance of Life.” Had she lived, perhaps interactive dance technology would have found a place in Cullen’s expanded vision given her persistent drive to bring together diverse peoples, artforms, systems and philosophies.

Achievement & legacy

Cullen’s achievement, writes Jones, is the making of “perhaps the most technically sophisticated interactive systems of the period, many of which have not been surpassed since.” Clearly, she was a great experimenter. Jacqui Carroll says of Cullen in a videotaped discussion between friends after the artist’s death, “she was interested mainly in the process of dance, the process of experiment.”

Stephen Jones’ exhibition, simply and effectively staged, is a fine, archivally thorough tribute to Philippa Cullen, to an artist who might be too easily forgotten, and to the collaborative experimentalists of the 1970s who gathered about her. Cullen could well become an inspiration to a new generation as she already has for Adelaide composer, musician and sound engineer Iran Sanadzade. As part of her Honours project in Sonic Arts at the University of Adelaide, Sanadzade devised her own movement-sensitive floor panels using updated electronics and staged a performance for four performers, titled If/Then (read Chris Reid’s review).

In this exhibition, its catalogue, in his book and articles, in collected images notebooks and extensive digitisation of the record, Stephen Jones has admirably secured the rightful place of Philippa Cullen in the history of Australian experimental art.

.jpg)

Stephen Jones

Dancing the music: Philippa Cullen, An Archival Exhibition for Philippa Cullen 1950-1975, curator Stephen Jones, SNO (Sydney Non-Objective Gallery), Marrickville, Sydney, 23 April-22 May

Video artist, historian, curator and electronic engineer Stephen Jones is the author of Synthetics, Aspects of Art and Technology in Australia 1956-1975 (MIT, 2011) which includes a substantial section about Philippa Cullen. From 1982 to 1992 Jones was a principal member of the electronic music group Severed Heads.

RealTime issue #134 Aug-Sept 2016