Trim, taut, terrific

Keith Gallasch: About An Hour

Joel Ma and family, In Between Two, Sydney Festival 2016

photo Prudence Upton

Joel Ma and family, In Between Two, Sydney Festival 2016

Sydney Festival’s About An Hour once again programmed intriguing, innovative works including In Between Two, +51 Aviación, San Borja, O Mensch! and the already reviewed Double Blind, Tomorrow’s Parties and This Is How We Die. The ones reviewed here are among my festival favourites with O Mensch! rating as one of the festival’s best, alongside Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker’s FASE and Vortex Temporum, Pascal Dusapin’s Passion, Woyzeck (with reservations), The Object Lesson and Meow Meow’s Little Mermaid.

In Between Two

In a logical but equally lateral extension of the modus operandi favoured by photographer-performer William Yang, In Between Two features two artists, life stories, projected photographs and live music. Where Yang has often been accompanied by a musician, here the performers are both musicians and accompany each other. Having two artists allows for both solo turns and dialogue, all framed conversationally and at a trot, contrasting with Yang’s engagingly deliberate rhythms which are also attuned to the way he paces his slide projectors. The overall design (Eugyeene Teh) is more palpably an installation with its angled screens and, in the distance, a long trail of vines, descending as if from branches far above and about to spread onto the stage. It’s evocative of Darwin and the Philippines which both figure strongly in In Between Two. Yang and Annette Shun Wah are the show’s dramaturgs, doubtless aiding the performers in whittling their complex tales into shape. The director, who has enabled these relaxed and confident performers, is Suzanne Chaundy. Visual designer Jean Poole seamlessly melds photographs, film and video.

The performers are Chinese-Australian spoken word and hip hop artist Joel Ma aka Joelistics and Filipino-Dutch-Australian guitarist, producer and songwriter James Mangohig. Both are well-known in the music world but will be new to most theatre-goers with whom they generously share their family histories, having first swapped them with each other as they became friends.

James Mangohig with father and grandmother, In Between Two

photo Prudence Upton

James Mangohig with father and grandmother, In Between Two

Mangohig’s Filipino father and Dutch-Australian mother, who were initially Christian pen pals (he would send her his sermons), married and lived in Darwin where Mangohig played with the rock band in his preacher father’s church until doubt set in and he left for surfing and the hard-drinking life of a musician. There followed two marriages, eventual professional success and reconnection not only with his father (“Tatu became less judgmental”) but with his Filipino heritage through the beloved Lola (Tagalog for grandmother), who visited Australia and whose farm he recurrently visited and helped sustain.

Joel Ma’s beautiful, energetic Chinese grandmother came to Australia from Hong Kong when she was 17, had several children and co-founded Sydney’s legendary Chequers nightclub in Sydney in the 1930s (there are wonderful photographs and film footage). She entered into a ménage à trois with her husband (a drinker and gambler) and a business associate in the 40s and years later watched her business fail as the Vietnam War broke trade relations with Australian markets. Ma’s admiration for his grandmother suggests a deeply felt emotional and creative kinship.

Ma’s parents were inveterate travellers, his father in love with music, his mother politically engaged, inheritances immediately evident in the opening number in which he raps about dope, jobs, racism, ghosts and, aptly for the musical form, “a galloping mind” to Mangohig’s supple bass accompaniment. Later he speaks about his sense of being defined as an outsider in the era of Hanson, Howard and the Cronulla Riot and how hip hop spoke to him and many others as a way to express themselves (as he did with the band TZU).

Joel and James speak of themselves as each other’s therapists. They’re good for us too, expanding our sense of what it means to be Asian-Australian, to achieve a sense of cultural heritage, to escape the strict dictates of religion and family but also to reconcile and be able to turn life into art with music and wit. The sooner In Between Two is restaged and widely so, the better.

Yudai Kamisato, Wataru Omura, Mari Kodama, +51 Aviacón San Borja, Okazaki Art Theatre

photo Prudence Upton

Yudai Kamisato, Wataru Omura, Mari Kodama, +51 Aviacón San Borja, Okazaki Art Theatre

+51 Aviación, San Borja

“We can’t overthrow the government through theater. Youth is wasted and society just ignores their passion. And above all, it’s a complete lie that there is truth on the Internet.”

These words are spoken by a disaffected theatre director in Okazaki Art Theatre’s +51 Aviación, San Borja. It’s one of the festival outliers, an oddly engaging, highly lateral work about cultural displacement. The show received little critical attention, a pity. Let me recall the ‘story’ that +51 Aviación, San Borja tells because the mode of performance is at once informal, complex and often not at all literal.

On a wide stage with a carpet striped with bright colours and surtitles on the walls behind, the performers wander in and out of frame with bags and suitcases, a few domestic props and a portable radio that mutters away for most of the show, as if the story is just… happening. A young theatre director (Yudai Kamisato) of Japanese heritage returns from Japan to the country of his birth, Peru, after 20 years absence. In Japan he’d failed to establish a sense of connection with his ancestors, his predecessors before his family left for Peru in the 1920s (as many had since 1898 hoping to make money as labourers and return home).

Attempting to make sense of his predicament, Kamisato creates a kind of avatar, the radical leftist Japanese theatre director Seki Sano (1905-1996), a political exile who went to Europe and Russia, worked with Meyerhold, was purged by Stalin as “a dangerous Japanese” in 1938, visited the US and went on to found contemporary theatre in Mexico. Having felt empty at the gravesite of his father’s predecessors in Okinawa, Kamisato fantasises conversations with Sano (a masked Wataru Omura) and a hostile theatre critic, preparing himself in effect for his return to Peru. But politically he’s no Seki, having no understanding, for example, of the island ownership disputes between China and Japan he hears about in Okinawa.

Yudai Kamisato, Wataru Omura, Mari Kodama, +51 Aviacón San Borja, Okazaki Art Theatre

photo Prudence Upton

Yudai Kamisato, Wataru Omura, Mari Kodama, +51 Aviacón San Borja, Okazaki Art Theatre

Once he’s home in Peru, Mari Kodama takes over the elliptical narration, leaving Seki Sano behind (we never learn what he did to justify being labelled “Father of Mexican Theatre”). Living with his grandmother in Lima (the play’s title is her address and country phone code), Kamisato commences the difficult process of re-assimilation. He finds an immigrant culture obsessed with Japanese food and watching NHK TV. The city’s streets and plumbing are poor, but there is a centre, established by the entrepreneur Ryoichi Jinnai in Lima—and in other countries with Japanese immigrant populations—which busses in the elderly for day care, a fine thing but another example of cultural dependency unlike Seki Sano’s break with Japan.

Things get whacky when the unsettled Kamisato is shoved in the street by a sociopathic religious zealot and nearly taken into a cult. More to the point, in the final scene, while attending the opening night of a theatre production and surrounded by Lima’s well-to-do in the foyer, Kamisato asks himself, as Seki Sano would have, “where are the people on the street?” Then he has to admit, “I’m not the people on the street,” perhaps realising he’s no Sano. Perhaps, having understood his condition by making +51 Aviación, San Borja, Kamisato—if he is in fact performing as himself—will be able to newly address the challenge of making political theatre.

The performance is casual, played directly to the audience and often as if improvised (a neck pillow of the kind used by passengers on planes on buses is grabbed from a pile of items to frame Seki Sano’s masked head, giving him the appearance of an Aztec god). But it’s also injected with moments of stylisation—Kamisato strikes emphatic Kabuki poses, his voice turning aptly guttural. Elsewhere there’s a discombobulated angularity and the voice slips registers. Omura’s Seki Sano is puppet-like, manipulated by the other performers—a gesture towards Bunraku. Those familiar with traditional and contemporary Japanese theatre would have detected further cultural signals in this fascinating work. It made an intriguing companion piece to In Between Two.

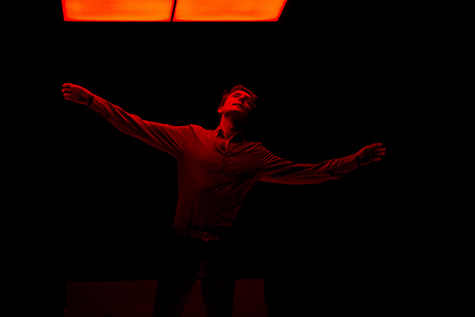

Mitchell Riley, O Mensch! Sydney Chamber Opera

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Mitchell Riley, O Mensch! Sydney Chamber Opera

O Mensch!

A grand piano sits to our left. Centre-stage, a casually attired, lone male figure stands on a short, steep set of steps. A cube of the same width and breadth hangs immediately above, emitting pastel hues which increase in intensity and frequency as the man’s feverish night-time imagination dwells on the delights and power of nature and on the social world that limits him in love, literature and more. As he compulsively returns to his querulous mantra, “For such an ambition, is this Earth not too small?” he tests the spatial limits of his confinement, discards clothing and courses emotionally from guttural utterance to falsetto flights to finally intoning gently against a steadily pulsed, repeated piano note—failure? resignation? He leaves his ‘cage,’ joins the pianist and delicately taps out the work’s last few high notes.

The work’s title—and its sung poems—come from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus sprach Zarathustra: “Human! Hark! What is the deep midnight saying?” The man, Nietzsche, is revealed in all his passion, vulnerability and arrogance in Pascal Dusapin’s fluent, finely graded and richly varied vocal score with its spare piano accompaniment (Jack Symonds) and baritone Mitchell Riley’s superbly integrated singing and acting—directed by Sarah Giles who partnered Riley for the gripping SCO production of the György Kurtág Beckett cycle…pas à pas-nulle part... . Riley’s restrained, subtly detailed naturalism engenders a believable young Nietzsche, allowing the moments of pain and anger to gain full expressive weight and sustaining a challenging 70-minute performance.

Mitchell Riley, O Mensch! Sydney Chamber Opera

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Mitchell Riley, O Mensch! Sydney Chamber Opera

There’s no production design credit for O Mensch! Presumably it was a collaborative effort, leaving much of the responsibility for making a spare set theatrically effective to lighting designer Katie Sfetkidis whose otherwise simple forward and shadow-casting side lighting allowed the LED colouring from the cube above to mirror Nietzsche’s volatility. Simply produced, O Mensch! is a work of huge emotional scale and another success for Sydney Chamber Opera.

Not forgetting Beethoven

In the top rank of festival highlights is another small outfit, the Belgian orchestra (or “period band” as such ensembles are often called) Anima Eterna’s complete Beethoven Symphonies, played on original instruments. I caught the 5th and 6th as a double bill in the intimate City Recital Centre, the ideal venue for a small orchestra, and the 9th in the vast Sydney Opera House Concert Hall where the woodwinds and sometimes the small Brandenburg Choir felt underpowered, certainly for those of us at the back of the first level of the dress circle. Nonetheless there was much to wonder at: a captivating scherzo realised in all its surging, swirling glory and an engrossing adagio with a slightly quickened pace that did justice to the capacities of the period instruments. The finale, with its expressive soloists, was forceful but, up the back in the reverberant Concert Hall, felt less than cogent.

As reviewers of the Anima Eterna Beethoven CD recordings have noted, there’s a revealing compactness in conductor Jos van Immerseel’s responses to the symphonies. This was most keenly in evidence in the performances of the 5th and 6th in the City Recital Hall; recurrent dynamic shifts from lyrical calm to tense pondering or passionate outburst were acutely marked and felt without being laboured in the 5th. Similarly Beethoven’s pervasive ‘minimalist’ repetitions in the 6th were mesmeric, heightening the sense of being immersed in the natural world which he portrays with such love. Even the relatively small-scale storm movement seemed more apt than the near-melodramatic turbulence unleashed by some modern orchestras. This compactness and its correlative lucidity allowed the period instruments to speak with clarity and character.

I felt blessed listening to the 5th and 6th, as if hovering, suspended between late Mozart and Wagner. It might be a fiction that we were hearing what Beethoven’s audiences heard, but it’s a happy fiction where the orchestra sounded sufficiently alien to make me re-think my relationship with the symphonies and the 6th above all.

–

Sydney Festival: Performance 4a, In Between Two, writers, composers, performers, Joelistics, James Mangohig, producer Annette Shun Wah, 21-24 Jan; Okazaki Art Theatre, +51 Aviación, San Borja, 21-24 Jan; Sydney Chamber Opera, O Mensch!, composer Pascal Dusapin, performer Mitchell Riley, director Sarah Giles; Carriageworks, Sydney, 22-24 Jan; Anima Eterna, Beethoven 5th & 6th Symphonies, City Recital Hall, 23 Jan; 9th Symphony, Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House, 25 Jan

RealTime issue #131 Feb-March 2016 pg. web