Trio: flight, death, earth

Keith Gallasch: Sydney Chamber Opera, Fly Away Peter

Brenton Spiteri, Fly Away Peter, Sydney Chamber Opera

photo Zan Wimberley

Brenton Spiteri, Fly Away Peter, Sydney Chamber Opera

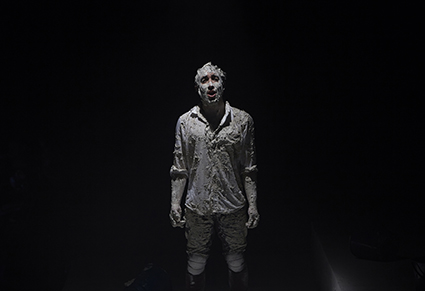

On a vast broadly stepped space, its flat white surfaces thickly textured, three people delight in the Australia they love and conjure in song—a particular landscape, its skies and, above all, its birds. The Great War takes two of them in body and one in spirit to the Western Front where they agonisingly delineate its horrors. Home or war, it’s the same abstract space—a designer’s tabula rasa for our projections (aided by haze, colour shading and silhouetting in battle scenes). The landscape’s whiteness now ironic, the muddiness of trench warfare is evoked by the white clay with which, aided by his comrades, the dying Jim coats himself, becoming one with the earth he acknowledges as his being: “grains of this body loosening.”

Composer Elliott Gyger’s glorious soundscape lends hearing to our landscape imaginings: with glissandi, microtones, harmonics, warbling, cries and whistling the chamber ensemble evokes pervasive birdcall, the rumbling trombone becomes an aeroplane and trumpet and trombone lead the musicians in a raucous march into the aural terror of industrial-scale warfare. Just as fine is the sense of transcendence—experienced by Jim, the protagonist of David Malouf’s novel Fly Away Peter—made musical. Like most modern operas on first hearing there’s little that is melodically memorable, but tensions, textures and states of being (contemplation, anger, fear: Jim’s haunting falsetto on “Am I dead?” and his silence after singing “I just want to make that sound [of fear] with you”—he soon does), can all be vividly recalled, the shape of the drama moreso than its music.

The fine actor-singers (Mitchell Riley, Brenton Spiteri, Jessica Aszodi) are at turns lyrical, passionate and anguished and their diction and acting excellent—particularly Riley with his easy presence and acute sense of physical and emotional detail. His performance in Gyorgy Kurtag’s …pas à pas–nulle part for Sydney Chamber Opera was equally memorable (RT119, p16), although more is demanded of him here.

Read David Malouf’s Fly Away Peter and you will find yourself immersed in the discrete consciousness of each of its three principal characters—Jim, Ashley and Imogen—in turn. In composer Elliott Gyger and librettist Pierce Wilcox’s opera adaptation, we encounter the protagonists as a trio, and although each has moments relatively alone, they share the same narrational, psychological, musical and stage space, three minds and bodies as one, embodying vocally the novel’s highly focused interiority and empathies, a world—as in the original—in which little is directly spoken between them.

If you know the novel you’ll most likely grasp what’s going on onstage, but if not, the experience of the opera will undoubtedly be impressionistic—the narrative floats in and out of focus, there’s uncertainty at times about who’s who. Spiteri plays all the secondary characters and Aszodi enacts a symbolic and choral role, for example in the laying out of a World War I memorial graveyard. Instead of allowing us to spend ample time with Jim initially, to shape our awareness of his love of birds and his ability to see the land ‘from above,’ the opera’s prelude introduces us to him, all too briefly, briskly adding his peers in chorus—Ashley (Spiteri), the enlightened, young wealthy landowner who asks Jim to manage his property as a bird sanctuary, and Imogen (Aszodi), a photographer. Their ‘out-of-time’ reverie celebrates their companionship and a joint passion to “fix the bird for eternity”—preserving, documenting and photographing. It’s difficult to fix on identities and relationships. Gyger and Wilcox then commence the narrative proper—with Jim and Ashley’s first meeting—unfolding it scene by scene, essentially in the complex trio form, doublings and with episodes that lack clarity—the Brisbane march in support of the war, just what it is a fellow soldier, Clancy, is asking Jim to do, and the discovery of mammoth bones in the trenches.

The decision to make the trio the musical centre of the opera, although admirable, has enormous ramifications for the dramatic construction of Fly Away Peter—doubtless there was much dramaturgical effort on the part of director Imara Savage to accommodate the consequent challenges, some deftly solved, others not. What could have been as lucidly accessible as the novel has become an opera that is in equal parts engaging and distancing. Fortunately, the final scenes are clearer, Jim sensing the war will go on forever, curious that “We do not meet the men who kill us,” and hovering between horrendous reality (the surgical butchering of the wounded) and redemptive dream (new, farmed growth in battle wasteland).

Enhancing the opera’s theatricality, Wilcox makes much of lists of the names of birds and soldiers, repeated phrases for the trio and spare sung dialogue, drawing closely on Malouf. Savage’s direction, using the entire width and height of the set, alternates her staging between stillness, physical tension (Ashley’s firm grip when Jim resists boarding the aeroplane), speed and violence (Jim’s raw battle with a hostile fellow soldier who turns out to be equally frightened). Before dying, before merging with the earth, before the final stillness, Jim sits, leans right, head in hand, nodding slightly in the most affecting image in the opera (sung as “a woman inside who rocks back and forth”). Mitchell Riley conveys much with simple expression and gesture, Elliott Gyger with a small, powerful ensemble and Imara Savage with a simple if monumental design by Elizabeth Gadsby.

If the trio structure makes the opera less than lucid and there are a scene or three too many, the excess I took exception to was Wilcox’s attempt to make the opera ‘universal,’ with a sentimental authorial intrusion at odds with the novel’s (and largely the opera’s) masterful realisation of Jim and Ashley’s limited worlds. He adds lists of the war dead, German, Italian and others. Although Jim might muse, “We do not meet the men who kill us,” these two profoundly inarticulate men, who sing their thoughts, have little consciousness of their enemy, let alone a wider world. Jim’s insight comes when he envisages the war from the air (“like building a pyramid”) and fears it is eternal.

While the novel’s ending is transcendent—Jim immersed in his vision of oneness with the earth and, finally, Imogen, her friends dead, inspired by the sight of a young man (a surfer) ‘running on the water’ and believing “the past will not hold”—Wilcox and Gyger end the opera ambiguously, their focus on the dying Jim, an image at once painfully tragic and musically liberating, realising the opera and the production’s potential.

Fly Away Peter has been another success for Sydney Chamber Opera, as ever meticulously and effectively conducted by Jack Symonds. Next to the superfluities of its last production, Mayakovsky, Fly Away Peter leans towards but does not achieve the clarity of earlier SCO productions. If it should be remounted, and it deserves to be, that’s an issue for composer and librettist. Too often, almost-there creations in Australia are not done the justice of re-working.

Carriageworks & Sydney Chamber Opera, Fly Away Peter, from the novel by David Malouf, composer Elliott Gyger, librettist Pierce Wilcox, director Imara Savage, conductor Jack Symonds, musicians James Wannan, Jaan Palandi, Peter Smith, Alison Evans, Rainer Saville, Matthew Harrison, Alison Pratt, design Elizabeth Gadsby, lighting Verity Hampson, movement Lucas Jervies; Carriageworks, Sydney, 2-9 May

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 48