True cause to celebrate

Keith Gallasch: John Zorn: Zorn in Oz

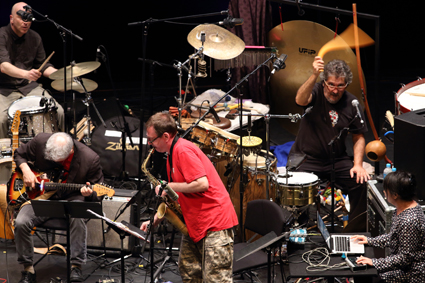

Joey Baron (drums), Marc Ribot (guitar), John Zorn (saxophone), Cyro Baptista (percussion), Ikue Mori (electronics), Zorn In Oz, Masada Marathon

photo Tony Lewis

Joey Baron (drums), Marc Ribot (guitar), John Zorn (saxophone), Cyro Baptista (percussion), Ikue Mori (electronics), Zorn In Oz, Masada Marathon

It’s a blessing when an arts festival has something really important to celebrate, it makes sense of the very idea— and doing it on a commensurate scale even moreso. John Zorn—composer, saxophonist, producer and nurturer of numerous projects across cultures and forms—has been a key player in the contemporary music scene in New York and well beyond since the mid 1970s. In acknowledgment of Zorn’s stature, festival director David Sefton invited him to stage four monumental concerts of his works with a huge cast of the highest calibre players from around the world, including Australia’s Elision contemporary classical ensemble.

Adelaide audiences and numerous insterstaters packed the Festival Theatre nightly, responding to joyous, accessible but complex music-making alongside demanding works, at all times with deep attentiveness, completing each performance with a standing ovation. The concerts comprised a program hosted by Zorn, sometimes playing, often informally conducting (on a chair facing the players or squatting on the floor) or leaving the floor open to a group or to the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra and conductor David Fulmer. Other than the quality of the playing (reinforced by excellent sound management), two factors made for a very satisfying experience: first, the variety of players (many of them long-term Zorn collaborators) and group permutations in each concert and, second, the sheer pleasure displayed by Zorn and his players as they revelled in having successfully tackled difficult passages or celebrated their team work with the audience.

Mark Feldman (violin), Greg Cohen (bass), John Zorn, Erik Friedlander (cello), Zorn In Oz, Masada Marathon

photo Tony Lewis

Mark Feldman (violin), Greg Cohen (bass), John Zorn, Erik Friedlander (cello), Zorn In Oz, Masada Marathon

Masada Marathon

Masada Marathon opened explosively with Masada Quartet. Zorn and trumpeter Dave Douglas each demonstrated trademark solo skills and mutual responsiveness—Zorn’s alto sax underlining Douglas’ smooth-to-raw scaling of the heights with counter medlodies, high speed flutterings and gurglings. Joey Baron, the ever-brilliant anchor drummer for most of three of the programs, and Greg Cohen on acoustic bass provided a propulsive foundation for a set that declared Zorn’s jazz mastery. Maphas followed: the duo Mark Feldman on violin and Uri Caine on piano delivering an intensely melodic trio of spacious, reflective, folk-inflected numbers without jazz markings, including a standout passage—jigging violin counterpointed with a striding piano. Mycale comprised four female singers including Zorn regular (he’s written some of his very best songs for her) Sofia Rei in an a capella set. There was another such set for four classically trained female singers on the fourth program. The structure was similar—a darker voice mostly providing a bass line, the group complexly harmonising and individuals taking solo leads. Sounds rather than words were sung, replete with accented breaths, sighs, pops and, at one point, ululations. The engaging melodies ranged tonally from Brazilian to Middle-Eastern, further revealing the expansiveness of Zorn.

John Medeski (Hammond Organ, Rhodes keyboard, grand piano), Trevor Dunn (bass) and Kenny Wollenson (drums) introduced us to three of the mainstay players for Zorn in Oz. Zorn’s music ranged from delicately reflective to pensive to rock attack, keyboard notes swirling or seemingly plucked from the organ while the bass sang. Next, Bar Kokhba marked the first appearance of Marc Ribot, Zorn’s favourite guitarist, fronting with Mark Feldman in a set that fully evidenced the composer’s synthesis of a variety of musical voices and influences: jazz, Latin, Jewish and Arabic and, from Feldman, Hot Club and gypsy jazz.

In Abraxas, Shamir Blumenkranz, on a North African sintir (or gimbri)—a square bodied camel-skin and timber guitar, long necked, three-stringed, deep toned and here forcefully picked—led an aggressively punkish set (suffused with moments of delicacy from the two guitars) in an open-ended interpretation of Zorn compositions (Abraxas: The Book of Angels, vol 19, Tzadik CD, 2012). In substantial contrast Erik Friedlander, solo on cello, and then in trio with Feldman and Cohen, displayed Zorn’s 19th century Romantic bent, if with trademark bending, quoting classics, playing with pizzicato possibilities and accentuated double bass plucking. Uri Caine’s solo piano set was note-thick with ragtime passages, lyrical turns and an ending focused entirely on the high end of the keyboard with crystalline clarity.

The concert concluded with the large ensemble Electric Masada playing Zorn jazz, again a coalescence of forms and influences, here from be-bop to free jazz to rock and everything goes, and quietly textured with Ikue Mori’s electronic whisperings, blips and whistlings largely heard in sudden silences in the playing. The set opened to a rapid beat with Zorn (a circular breather) sustaining an epically long, raw note which broke into a massive chord shared with the ensemble and out of which flowed a Middle Eastern riff. Zorn-conducted single staccato bursts from each player, a return to the big chord, a Ribot-led crescendo, and then calm with electronics and a grand, soaring sax finale. This was a memorable piece in an altogether memorable concert. Not one to let us rest, and signalling more forceful music to come, Zorn’s final offering was heavy metallish, sax raging and percussionist hero Cyro Batista pounding (while tinkling and stroking many an other object) a huge bass drum.

Classical Marathon

Zorn’s classical outings reveal great knowledge of and kinship with mid to late 20th century Modernism. In a field dense with invention and competition it’s not easy to rate the quality of this music, let alone on first hearing, but it’s largely engaging, and expertly acquitted by the Elision ensemble. Cellist Severine Ballon excelled in A rebours where she is required to attack, pluck and glide, be silent and grow melancholy in the manner of Shostakovich, as bell, drum and flute journey with her to a formal ending. The richly engaging Sortilege features two bass clarinettists (Carl Rossman, Richard Haynes) in a dialogue delightful and dramatic, running deep, soaring weirdly high, shushing, rushing, mellifluous. Zeitgehoff, a world premiere, also evoked something Russian, violinist Graeme Jennings and cellist Ballon also in dialogue, their instruments tensely creaking and buzzing at the edge of comprehension.

The second half of the concert featured the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra under David Fulmer. Elision’s Graeme Jennings fronted the orchestra in Zorn’s Contes des Fees, the music for the violin reminiscent at times of Prokofiev, sweet lines over string-powered depths followed by passionate outbursts, a wind machine (corny as ever) and a final romantic coalescence of orchestral forces.

Kol nidre was something altogether different—a simple sacred melody, centred on the strings, darkly toned and, overall, shaped with Minimalist precision by Zorn with a recurrent, emotionally potent swell (well realised by Fulmer). The final and longest work (all the others ranged from 8 to 12 minutes), Suppote et Supplications (25 minutes), featured sparkling percussion, vibrant drumming, surging orchestral forces, delicate harp and crotale interplay and a powerful and a distinctive mass double bass passage prior to a long, delicate ending. Not an easy work to estimate, but absorbing moment by moment, and again, rapturously received. For Elision in particular this must have been a very special night, playing to what was apparently the biggest audience in their career. A great night for new music.

Greg Cohen, Dave Douglas, Joey Baron, John Zorn, Zorn In Oz, Masada Marathon

photo Tony Lewis

Greg Cohen, Dave Douglas, Joey Baron, John Zorn, Zorn In Oz, Masada Marathon

Triple Bill

The third program was another of great variety. One of Zorn’s seminal works, Bladerunner, featured the composer, the great bassist, arranger and producer Bill Laswell and, on a massive drum kit, heavy metal drummer Dave Lombardo (his only appearance). We were in for our first bout of serious aural assault. But before unleashing his bird calls, stutters, flutters and wild cries, Zorn delivered solid, romantic noir sax against Laswell’s fretless, high reverb songful bass. Lombardo let loose, eclipsing the bass, but Zorn held firm. The three numbers revealed subtleties amid the roaring: for example, Laswell, once heard, created a cathedral ambience while at other times milking bass buzz and unusually high resonances.

A complete change of mood came in the form of Essential Cinema, four short films shown on a large screen while the Zorn Ensemble played in near darkness. Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1936) is a cut-up of a forgotten Orientalist Hollywood movie, its excesses (Eastern potentate, volcano, alligators, wild natives, eclipse) and symbolism (sexual) juxtaposed with Marc Ribot’s languid guitar with its own brand of Latin American exoticism. For Harry Smith’s The Tin Woodman’s Dream (1967), Zorn nicely blends the magical animation with lilting percussion and organ. Aleph by Wallace Berman (1966) is a wild montage of celebrities, comic book characters and nudes to an aptly speedy score led by Zorn’s chatty sax. The most fascinating of the films was Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946) by Maya Deren, an eerie, elusive narrative about three young women, one increasingly nun-like and suicidal, all seemingly in search of men. The party scene where everyday movement becomes dancerly reminded me of DV8. The cogent score in part centred on an initial melancholy cello theme, vibes for the party, electronics for an encounter with a statue-become-man in a garden, greater forces for the young woman’s panic and a spare pulse for the spooky ending: lillies floating beneath a jetty,

The last event of the evening a 12-strong ensemble was Zorn’s famed Cobra, a game playing model for semi-constructed improvisation. Zorn likes structures that yield such freedoms. Across the four nights musicians peered at scores; here they watched Zorn as he waved cards at them (a number or an indicator meaning, for example, do something in particular but in your own way) or put on his peaked cap to indicate he wished to conduct. Once engaged the musicians point to each other to form duos and trios within the greater framework. The thrill of Cobra resides in the pace and richness of inventiveness and the emergent cohesiveness. Of the four games, the second yielded a tight trio in the form of Feldman, Friedlander and Dunn and deep-end piano subtleties from the formidable John Medeski. The third was the most distinctive, sounding least like an improvisation, replete with silences, soft percussion and keyboards and a very unusual emergent melody, a quiet prelude to the all-stops-out fourth.

Zorn@60

Zorn@60 commenced with one of Zorn in Oz highlights, The Song Project. Zorn has composed more than 500 songs for various artists, 10 or so of them heard here, including some of the best known: Jesse Harris sings “Tamalpais,” Sofia Rei “Besos de Sangre” and Mike Patton “Batman” to the glorious accompaniment provided by Baron, Batista, Medeski, Dunn, Wollenson and Ribot. The singers alternate solos and back each other up, Rei for Patton’s “Dalquiel,” Rei for Harris in “Towards Karifistan,” with its gorgeous Cuban piano line. In “Mountain View” bassist Dunn flawlessly replicates and transforms the melody and the ensemble turns big band. Patton sings a tribute to Lou Reed and the trio wrap up with the rock-pop “In the City of Dostoevsky.”

The Holy Visions comprises five women, sopranos and mezzos in long white dresses, singing a capella, Zorn’s compositions evoking everything from Renaissance song to the Swingle Singers, Berio and Meredith Monk with fluency, cogency and great singing. The final song, with its chiming voices and small bells ends with a simple, sublime exhalation. Elision returns to the program with Zorn’s The Alchemist, for two high flying violins, viola and cello in a dark tide of sound, restless, suddenly fast and then quite formal.

Moonchild—Templars: In sacred Blood held the Mike Patton fans in gothic rapture. Inside the barrage of sound, Patton’s screams are complex, replete with whoops, clicks, whispers, flutters, amazing glides, falsetto and occasionally the singer’s elegant baritone—melding with Dunn’s rapid, dancing bass playing (plus string scraping and heavenly harmonics), Baron’s unforced drive and Medeski’s sustained deep organ notes and complex flourishes. Patton is something to watch, limbering up before leaping into song. If you’re not a fan or new to Patton, it’s a rough, if short-lived ride. RealTime Contributing Editor Darren Tofts emailed me:

“Everyone should hear ‘Osaka Bondage’ performed live at least once in their lifetime. 78 seconds of the most sublime racket ever to trouble the airwaves. I heard it in Adelaide and am still vibrating.”

Sparer pieces like the slow burning “Vocation of Baphomet” gave initiates a taste of Moonchild’s appeal, while the finale “Secret Ceremony” illustrated the dramatic range of both composition and performance. You can judge for yourself; a full concert of Moonchild at the Moers Festival can be seen on YouTube, among other works that also appeared in the Adelaide Festival program.

The end of Zorn in Oz draws near with Zorn’s core players appearing as The Dreamers, with the no less superb Jamie Saft replacing the great Medeski in a set ranging from jazz to complex rock, a prelude to Zorn joining them for Electric Masada with Wollenson also on drums with Baron and Ikue Mori on electronics. In the first number there’s a touch of Spain in Zorn’s mellow sax and a well-deserved long solo from Ribot. In the second a big rock guitar launch gives way to passages of limpid Rhodes playing from Saft, soft vibes, whistles from Batista and a dark guitar melody. Finally Zorn leads a huge atonal rock march which grows hymn-like. The audience rise as one in celebration of a truly generous musical giant whom we watched seated amid his colleagues, intermittently conducting, playing vigorously, smiling, encouraging, rewarding.

–

Adelaide Festival, Zorn in Oz, Adelaide Festival Theatre, 11-14 March

RealTime issue #120 April-May 2014 pg. 20, 56