Unseen, all too visible

Linda Marie Walker

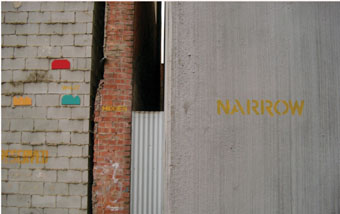

Nick Harding, Narrow, 2003

photo Linda Marie Walker

Nick Harding, Narrow, 2003

Recently, while visiting Jim Moss’ new house/studio, designed by the late Nick Opie, I saw an ‘exhibition’—2 paintings by Ian Grieg, one a patterned black work in 2 parts, the other a grid of a repeated water image. Both were Grieg’s gifts to the house. In Kay Lawrence’s office around the corner from mine in the city are many exquisite woven works by various artists (including Lawrence). Across the road in a streetwear shop is a set of prints by the urban artist KAB 101 (shown to me by Anton Hart). And a little further down Hindley Street on an old cinema hoarding there is this sign:

BLOTCHWOMAN>KAB101>SPROUTBOY

PRESENTS

VOID IF REMOVED

(Beneath this sign is a whole ‘cinema screen’ of characters, scenarios, colour fields and texts; the cartoon face of Blotchwoman, for example, has appeared throughout Hindley Street over the last few years—she’s a ‘filmstar’ of the West End). In artists’ studios there are innumerable works that never see the light of day. On my own loungeroom wall there is a new John Barbour work.

Sometimes, perhaps always, there is art ‘all around’—not organised to be officially viewed, or offered as officiated presentation, but nevertheless ‘exhibitions’ that one sort of bumps into. Then there are, in more ordered and contained ways, sites where art appears outside designated galleries, like shop fronts, artist-run spaces, clubs, library foyers, corridors etc.

In the ‘all around’ premise, art and architecture become the ruins (or erosion) of each other. They take within themselves—absorb their own appearance, as if holding themselves to themselves—the singular presence of their appearance in the world as odd, as stubborn manifestations of conscious effect. What I mean is that art and architecture, when they appear together like this, resist incorporation—however mild—into the straight-line of dominant (art) sense, and wind up in the middle of contrary stories. A shattering beauty results. The black Grieg is high above the silver stove, catching the summer light from the west. It’s as if one ‘finds’ it there. One finds, in some way—by chance or invitation—these works and their architectural context (in the case of the Grieg, one’s eye is drawn to the height of the wall, and to the upstairs space).

And then…one finds entire (planned) exhibitions right under one’s nose (and just a little to the side of the galleries one usually haunts expectantly) which seem to be about—or so one imagines—the very idea of space-gift, of the ‘found’, of what is there (in the present) for the taking.

In his first solo exhibition NARROW, Nick Harding has used the limited space of the Flightpath Architects’ office to arrange a set of small digital photographs taken within a 100m radius of the space. These poetic, quietly composed images are each of a liminal or marginal space, an everyday architectural moment of endurance—an infinite moment of abandonment; the compositions are only just there—chosen from a tiny territory that effortlessly offers endless imagistic opportunities. Here in the strict angles of architecture—brutal corners, gaps, planes, grids, materials—a ruinous activity of surface subtraction and addition undoes and redoes the appearance of the world, as if an art of constant reworking (“sweet disorder”, says Jane Rendell in Occupying Architecture, Between The Architect And The User, ed Jonathon Hill, Routledge, London & New York, 1998). There, where no-one’s looking, stories come and go, the city’s undercurrent messes with its wrap of staid geometry, pulls it out of alignment and occupies it. The wrap is an invitation, an offered surface—the word NARROW in yellow on a grey concrete wall, with the word HIDDEN on the bricks nearby; a compelling Mondrian, by ‘someone’, appears in aqua and blue on the back of a building. This ‘someone’ is a crowd, an amalgam of strange energies, which employs strategies to liquefy the meaning of space; the space of architecture is borrowed and given its proper due—a love without judgment. Time, ‘someone’, shifts it ‘all around’; Harding records 11 shifts of time.

Jason Namakaeha Momoa makes 3-dimensional collages from the fragments of time left lying around on streets and rubbish tips, in sheds and shops. Not revelations nor didactic evocations, the collages are all brownish, modest, worn and crumbly. They are ‘poems’ which trust that their materiality—in its acquired broken, ruined, melancholy beauty—will not be dismissed via the language of nostalgia or longing, but will be taken on in other less ready terms (like, corrosion, accretion, duration, and attention—an attention of minute intensity, eg why has that small cardboard box been reinforced with metal strips?; to what picture did those canvas prayer flags once belong?).

Namakaeha Momoa’s solo exhibition, The Brown Bag Diaries, is hung in the central space of Kintolai Gallery, right next door to Harding’s exhibition at Flightpath Architects. The 10 mixed-media works, in their role as ‘collage’ or ‘construction’, belong to the long history and tradition of making-do, combining and juxtaposing (although juxtaposing, as a way of infusing ‘meaning’, is of little concern here; each element pretty much keeps its own counsel) with exceptions if one bows to clues. Several of the works use the back of picture frames as the ground/surface on which to apply other minimal materials—a piece of barbed wire (Hokusi), a drink coaster (Eye Of The Holder), a metal disk (Barn Burned Down Now I Can See The Moon)—and these grounds are themselves rich, porous, and textured, whole regions of nuance.

Viewed together these 2 exhibitions speak in similar tongues. In Harding’s work the collage is ‘found’ and left in place, yet ‘taken’ too—extracted pictorially. In Namakaeha Momoa’s work the collage is found in disparate pieces in disparate (local) places, physically ‘taken’ and ‘given’ back out of context and architecturally ‘planned.’ They look like maps of curious interiors or floor plans for future structures: “Things in ruin give shape to the new structures, they are transfigured and changed. Like the tail of a comet they detach themselves from the cathedral. The whole world and the whole memory of the world are continuously designing the city” (Alvaro Siza in Bruno Marchand, “Inspired By Ruins”, A + U, 355, 2000).

One comes across these 2 bodies of work, they emerge within the wider circle of the contemporary visual arts and perform (consort) with the works one finds ‘all around.’ They gather, momentarily, a crucial imminence, or in Harding’s exhibition notes about liminal space, an “ambiguity; a marginal and transitional state, a transitional passage between alternate states…neither one place nor another; neither one discipline nor another; rather a third space in-between.” And, to extend this notion of ‘neither/nor’, across the street (Hindley Street, one of the great small streets in the world, let’s hope it doesn’t get cleaned to death) from both these exhibitions is the State’s organisation for the arts, Arts SA. Within these offices is an extensive exhibition of South Australian art curated by Julie Henderson and Joe Felber that will go ‘unseen’ by almost everyone—neither public nor private. This brings up, into the political cultural arena, the necessity (and urgency) for a location—an architecture (one of those sites recorded by Harding, and fantasised via an amalgam of Namakaeha Momoa’s ‘floorplans’, for example)—dedicated to the collecting, curating and showing of South Australian visual art (an archive, research facility, gallery, a site for events, residencies, education). A location that seriously takes up (consolidates and extends) the multifarious and complex work of our contemporary visual art spaces, commercial galleries, the state-wide South Australian Living Artists Week, artist run projects, studios, offices, shops, sheds and lounge rooms.

What Harding and Namakaeha Momoa’s exhibitions ‘exhibit’ is an indication of the vast passing of ‘local’ imaginings and intimate sensibilities which if valued and attended to would help reveal the specific and manifold resonances that a particular human environment is—in its extraordinary ‘doing’ endeavours. “Through telling new stories, the unknown, undiscovered city can be laid open to critical scrutiny, to new urban practices, new urban subversions…I would like to suggest that the unknown is not so easily known—indeed, it may be all too visible, right in front of our eyes…” (S. Pile in Rendell, Occupying Architecture, Between The Architect And The User).

Thanks to the artist Joe Felber for a conversation about the huge uncollected collection.

NARROW, Nick Harding, Flightpath Architects, Hindley Street, Adelaide, Dec 2003-Jan 2004; The Brown Bag Diaries, Jason Namakaeha Momoa, Kintolai Gallery, Hindley Street, Adelaide, Dec 2003-Jan 2004

RealTime issue #59 Feb-March 2004 pg. 34