Virtual restoration as theatre

Caroline Wake: Yoko Ono, Joan Jonas, Mark Rothko

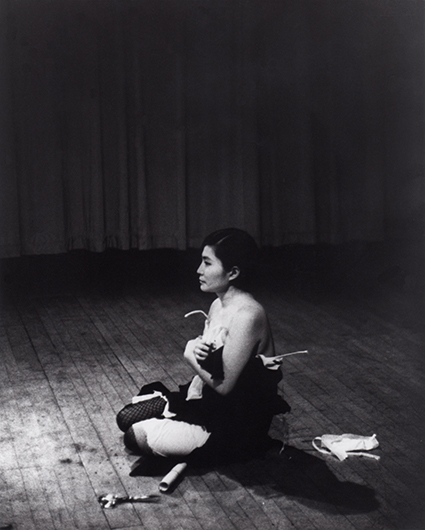

Cut Piece (1964) performed by Yoko Ono in New Works of Yoko Ono, Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, March 21, 1965

Photograph by Minoru Niizuma. Courtesy Lenono Photo Archive, New York

Cut Piece (1964) performed by Yoko Ono in New Works of Yoko Ono, Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, March 21, 1965

The relationship between performance and the gallery has come under renewed scrutiny lately, however it has a long and complex history. Of course, further complications ensue when this history itself is returned to the gallery in the form of an exhibition. On a recent trip to Boston and New York, I saw three such exhibitions.

Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-71

In New York, the Museum of Modern Art is staging a retrospective of Yoko Ono’s work. The date span covers the first decade of her now 55-year career, starting with Painting to Be Stepped On (1960-61) and finishing with her unofficial exhibition at MoMA in 1971. That year, she advertised a “one woman show” titled Museum of Modern (F)Art but when visitors arrived there was nothing more than a sign stating that Ono had released some flies on the museum grounds and the audience could now follow them throughout the city. If the former introduces her aesthetics of interaction and instruction, then the latter demonstrates her flair for the ephemeral, the playful and the critical. In the intervening years, Ono also honed her performance and experimental film practices and, of course, met John Lennon.

Each aspect of her practice survives slightly differently in the exhibition format. Obviously any institutional critique is diminished but this is counterbalanced by the instructions, which retain both their clarity and beauty. The exhibition augments the aura of the original Grapefruit (1964) instructions by installing the typed yellow cards on a white wall. I appreciate their elegant analogue aesthetic, in the same way that I enjoy the simplicity of putting my feet on the Painting to Be Stepped On. Elsewhere, however, the interactive elements suffer, paradoxically, from the presence of too many people.

On the day I visit, there is a line for Bag Piece (1964), which consists of a black bag on a low white platform. One at a time, visitors hop into the bag and stretch, crawl or roll—in privacy but in plain view. Visitors also have to wait to climb Ono’s new work, To See the Sky, a black spiral staircase that heads towards the heavens, which happen to open up on the day I’m there. I tilt my head back to admire the storm through the skylight before heading back down. In contrast, Ono’s famous Ceiling Painting or Yes Painting is there but audiences are not allowed to climb the ladder, merely to admire it. Does it still say “Yes”? I can’t tell you.

We are allowed to play with a copy of the White Chess Set (1966) in the Sculpture Garden, but only for three hours a day, four days a week and my visit doesn’t coincide. Speaking of sculptures, Apple (1966), which consists of an apple on a plexiglass plinth, and Half-A-Room (1967), a series of domestic objects sheared in half, are the low point of the exhibition and lack the complexity of some of Ono’s other work. Last but not least, it is a pleasure to be able to see films like Film No. 4 (1966-67) and film documentation of performance like Cut Piece (1964), in a higher resolution and larger format than the versions circulating on the web.

Yoko Ono interacting with people activating Bag Piece (1964), a participatory work in Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971, on view at MoMA, 17 May-7 Sep 2015

Photo Ryan Muir © Yoko Ono

Yoko Ono interacting with people activating Bag Piece (1964), a participatory work in Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971, on view at MoMA, 17 May-7 Sep 2015

I leave the exhibition having enjoyed the ephemera—the Grapefruit cards, the Fluxus correspondence, the performance documents—but feeling as if I have somehow missed the more interactive and playful aspects of Ono’s practice. Perhaps it is because Sydney just had a Yoko Ono exhibition or perhaps it is because the institution of MoMA and the spectacle of the summer blockbuster have overwhelmed the delicate practice that is performance: either way, I feel as if both Ono and I have been shortchanged.

Joan Jonas: Selected films and videos, 1972-2005

Born just three years after Ono, in 1936, Joan Jonas is this year’s US representative at the Venice Biennale. To coincide with this, the MIT List Visual Arts Center organised a small retrospective of her earlier video works. The first work you see is Good Night Good Morning (1976, 12 min), for which she recorded herself greeting the camera at the beginning and end of each day for three weeks. Clad in pyjamas, silky robes and on one occasion just a sheet, Jonas performs both intimacy and duty. Indeed, it’s almost like a miniature, feminised and feminist version of Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980-1981 (Time Clock Piece).

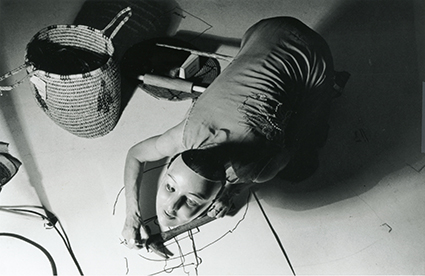

To the left of this work is Organic Honey’s Visual Telepathy (1972, 17 min), a work full of masks and mirrors, halves and doubles, water, hammers and fractures. In it Jonas assembles and disassembles her double, Organic Honey, by donning and doffing a waxy doll-faced mask and an elaborate headdress and then performing a series of inscrutable rituals. She stands in front of a fan, a jar of water, and several different mirrors of different shapes and sizes (polygon, circular, triangular). Each prop destabilises the image in a different way: the fan wafts her hair upwards, the water throws a wobbling glow onto her face, and the mirrors refract her face into the centre of the frame and reflect her gaze back at the viewer.

In another ritual, her elegant hand traces a series of objects including a doll, a roll of electrical tape, a spoon, a doorstop and a hammer. In the next frame, she appears to bang two hammers together until a crack in the image reveals that one is a reflection of the other. Towards the end, Organic Honey laughs, but without any facial cues to accompany it, this hilarity is creepy. It finishes with Jonas’ bare face: illuminated and then extinguished in full and then in halves before the image blacks out. Even though it’s over 40 years old now, this strange, seductive work feels completely contemporary.

Joan Jonas, Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll, ACE Gallery, LA, 1972

photo Roberta Neiman

Joan Jonas, Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll, ACE Gallery, LA, 1972

Inside the main room, one screen shows a series of four works: Songdelay (1973, 19 min); Mirage (1976, 31 min); Double Lunar Dogs (1984, 24 min); and Volcano Saga (1989, 28 min). The first and fourth of these provide some fresh air after the rather interior pieces that induct the viewer into the exhibition. In Songdelay, several performers (it is hard to tell how many, but there are 15 in the credits including Steve Paxton and Gordon Matta-Clark) enact simple choreography in several locations (again, it is hard to tell how many). Standing in an abandoned lot, they bang wooden blocks together, occasionally interrupted by the low horn of a boat that then glides by on the river behind them. The image and sound are out of sync, probably because sound always arrives slightly behind the image it accompanies or possibly because of the editing. It’s a clever deconstruction of liveness, which is premised on the synchronous, spatiotemporal co-presence of performer and spectator. But where does presence end and distance begin? When the audience stands even a short distance away, optics and acoustics no longer coincide and the performance becomes—even before it is recorded and remediated—asynchronous. There is a politics to this, as revealed in another scene where the men in the foreground talk about taking a vow of silence while ignoring two women in the background who are yelling at each other “listen to me” and “come here.” Only those who are already seen and heard can contemplate the pleasure of withdrawing from the economies of visibility and audibility.

The last video is Lines in the Sand (2002-2005, 48 min), a recording of the performance Jonas made for Documenta 11 in 2002. Taken together, these videos remind me of the inherent theatricality of Jonas’ artistic practice. While many of her contemporaries were proclaiming the singularity of performance—its inability to be repeated—Jonas routinely returned to her pieces, remounting and remediating them even before the latter term existed. Perhaps this is why I am less troubled when she returns to early work as opposed to say, Marina Abramovic, who always rejected theatre’s repetitions.

Mark Rothko’s Harvard Murals

Beyond being in Boston, there would seem to be little connection between the Jonas exhibition at MIT and the Rothko one at Harvard. From a different generation, working in a different medium and market, Mark Rothko poses a different curatorial problem. If the task for the Jonas curator is to familiarise an audience with an artist whose work is not as famous as it deserves to be, then the task for the Rothko curator is to defamiliarise an artist whose work is instantly recognisable. Nevertheless, I find an unexpected connection between the two exhibitions via theatre.

The Rothko exhibition centres around five murals, commissioned by Harvard in 1961 and installed in the dining room of its Holyoke Center in 1964. Rothko did 22 sketches and 10 murals, six of which were brought to Harvard. In the end, only five were installed—a triptych on one wall and two standalone pieces—so the sixth went to his children who rolled it up and placed it in storage. It’s an important detail, because by 1979 the sunlight in the dining room had so badly degraded the red pigments in Panels One to Five that they had to be removed. Now, 36 years later, the paintings have been “restored” to their former glory through a new, non-invasive method of digital projection.

Unable to touch the paint, the conservation team determined what the paintings looked like in 1964 by looking at old photographs (which also had to be restored) as well as taking colour measurements from the uninstalled Panel Six. This gave them what they call a “target image.” They then photographed the panels in their current state and set about developing a “compensation image” through a series of algorithms. The final compensation image has over two million pixels and is then projected onto the original panels, rendering them in all their sublime, saturated glory. It’s the first in a series of moments throughout the exhibition that strike me as theatrical: for all its technical accomplishments, it’s an almost old-fashioned use of theatrical lighting. In addition, there is the exhibition room itself, which replicates the dimensions of the original dining room. On the far wall, as you enter, is the triptych; behind you, are the other two panels. Both of these walls are painted an olive-mustard colour, as the original ones were. To the left and the right, the walls are left white to signify where the windows would be. Once again, this strikes me as theatrical, which is to say it’s almost a set.

Of course, it is impossible to appreciate just how much work this set and these projections are doing without a point of comparison, a problem the exhibition solves in two ways. Spatially, it has the audience enter through a room where Panel Six hangs alongside several studies; these are set against a white wall rather the yellow we see next-door, meaning that the reds are nowhere near as sumptuous. Temporally, the moment of comparison manifests at 4pm each day, when the projectors are turned off. On the afternoon I attend, at least 40 people come from around the gallery to witness this moment. The head of security introduces himself, explains the order in which the projections will be extinguished and then, pulling his smartphone from his pocket, proceeds. Yet again, I think of theatre, specifically the tradition of the “reveal,” and appropriately enough the audience gasps. When the projections disappear the paintings are vastly different: the lush, infinitely varied pinks, cherries, maroons, and blood-blacks lose their depth and range and become dull, flat and even.

If Yoko Ono confirms the suspicion that performance can never be properly documented or remediated, and Joan Jonas adds an important caveat by suggesting that it can, especially when the performance itself is already mediatised, then the Mark Rothko installation goes even further. When strategies of lighting, sets, live bodies and reveals combine with highly sophisticated media technologies, the result is more performance-like than even exhibitions that are explicitly devoted to it. Yet again, the relations between gallery, theatre and performance have been recalibrated for me.

Exhibitions: Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-71, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 17 May-7 Sept; Joan Jonas: Selected Films and Videos, 1972-2005, MIT List Visual Arts Center, Boston, 7 April-5 July; Mark Rothko’s Harvard Murals, the Fogg Museum, 16 Nov 2014-26 July 2015

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg. 14-15