Visual Arts, RealTime 1994-2004: Part 2, Convergence & Resurgence

This is Part 2 of a two-part look at RealTime’s visual arts coverage. Read Part 1 here.

In the second part of this overview of RealTime’s visual arts coverage during its first decade (1994-2004), I’m struck by how deeply the magazine’s writers engage with their material, keenly examining it from a range of angles. Here, they illuminate the complexities of cross-cultural exchange arising from new waves of contemporary Asian art; contextualise the millennial flourishing of photography, painting and video art; and bring linguistic playfulness to idiosyncratic installations.

For access to reviews in RealTimes 1-40 I’ve provided links to each edition and page numbers for you to scroll to. Reviews in editions 41 to 64 are directly linked.

Asia, Australia & cross-cultural complexities

A tendency towards glib globalisation is critiqued in several RealTime analyses of cross-cultural initiatives, particularly those involving Asian cultures.

“[T]o go beyond the simplistic essentialising of other cultures, a process of continual cultural contestation must take place,” writes Christopher Crouch in his report on the Symposium on Urban Dynamism in Asian Art, convened by the Art Gallery of WA to accompany the touring exhibition Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions and Tensions [RT 24, p 43]. Crouch recounts the conference’s unintentional – yet fortuitous – demonstration of the ways in which cross-cultural negotiations fall down, resisting attempts to unify via a “coherent cultural structure that could encompass the different contexts of production and consumption of the works in the show.”

In “Tran’s Emporium opens up” [RT 28, p 29], Jo Law incorporates her own experiences as a Hong Kong-born Australian artist in an excellent overview of the problems underlying ‘multiculturalism’ as it manifests in marketing campaigns, cultural exchange programs, appropriative art-making and showcase exhibitions. In the pursuit of superficial feel-good results, too many factors that should be inherent to the process of cross-cultural collaboration are neglected:

“Doubtless, cross-cultural activities are invaluable in many ways, but it is important to establish a structure that will allow us to benefit from interacting and learning from different ways of life. The process of cross-cultural reading and practice needs to be more autonomous, more democratic and less institutionalised; independent initiatives should be welcomed and supported. Furthermore, the very notion of cultural exchange should be interrogated and this process should be a central objective in such activities.”

From Sonamu, series B 1992-97, Bae Bien-u, The Slowness of Speed – Contemporary Korean Art, National Gallery of Victoria, 1998

In her review of the exhibition of Korean contemporary art at the NGV, The Slowness of Speed [Cultural pace and individual acceleration, RT 30, p 42], Lara Travis notes, “It is a relief to visit an exhibition of contemporary Korean art and not be bombarded with rhetoric about cultural exchange and the diaspora, which has surrounded so many Asian art exhibitions and has, through overuse, acquired a diplomatic tone too expedient to be fully credible.”

Li Ji Warrior Girl, Kate Beynon, 2000, courtesy the artist, Australian Perspecta 1999 featured on the cover of RT #32

On the same page, below Travis’ review, Hong Kong-born Australian artist Kate Beynon enacts a personal cross-cultural negotiation in a series of comics-style drawings of a pregnant action-heroine alter ego, depicted through a fusion of Chinese and Western iconography [Fluid significances, RT 30, p 42; see also cover image RT 32 above]. Reviewer Sandra Selig points out the simultaneous harmony and dissonance resulting from Beynon’s hybrid approach: “Beynon’s drawing finesse produces a seamless intersection of particular Eastern and Western graphic styles while retaining a stylistic incompatibility or difference.”

In late 2001, another artist embraces hybridity as a means of expressing his own cross-cultural identity and experience. In a vivid review, Anne Ooms [Filipino high kitsch with crab creole and politics, RT 45] evokes Perth-based Manila-born Alwin Raemillo’s enjoyable multi-sensory installation Semena Santa Cruxtations, showing at 24HR Art, Darwin, a lurid performative mashup of food, Catholic iconography, fast food advertising and Australiana that lampoons the Catholic Church and globalised business. In responding to Raemillo’s work, Ooms underlines the difficulty that attends this collision of cultures: “In the modern world radical differences are clustered together, constructing irresolvable contradictions. An ethics embracing cultural diversity becomes a necessity.” (Note the shift away from the use of “multiculturalism.”) She identifies Tropical Darwin as the perfect location for the exhibition, being “on the edge, where the complex and brutal consequences of colonisation are daily confronted and a migrant sensibility seems the norm.”

Djon Mundine in 2002 is inspired to write about VietPOP, an exhibition of seven young Vietnamese-Australian artists at Liverpool Regional Museum [VietPOP: a new generation speaks, RT50]. The exhibition tackles a number of intercultural issues, including the core refugee experience that nonetheless leads to a range of disparate relationships with homeland, adoption into white families, critiques of globalisation and the differences between these artists and their parents’ generation. International Vietnamese-Japanese art star Jun Nguyen Hatsushiba, included in the exhibition as mentor and counterpoint, provides other sources of cross-cultural conversation, by virtue of his dual heritage and the subtle ways in which his background differs from his fellow exhibitors. In his review Mundine broadens the conversation to include comparisons with Aboriginal communities.

Photography: analogue, digital & the natural

RealTime’s extensive coverage of photography reveals the way this multivalent medium came into its own in the 1990s, with its importance and centrality to contemporary art cemented by the 2000s. Large-scale surveys of the form were mounted at state galleries while pioneering contemporary Australian photomedia artists rose to prominence. RealTime writers examined photography’s mutable identity, its tendency to complicate the relationship between the natural and the artificial, the ethics of representation, and the gradual shift from analogue to digital technology.

Responding to The Power to Move: Aspects of Australian Photography, an exhibition of photographs from the Queensland Art Gallery collection [The death of (the) art (of) photography, RT 12, p 41], Peter Anderson traces the relatively recent trajectory of photography as an artform in Australia. Quoting from curator Anne Kirker’s catalogue, he notes that the period of active collecting of photography in Australia, dating back to the early 70s, coincides with “the period when photography became recognised as an artform appropriate to a culture searching for a democratic alternative to the traditionalism of painting and sculpture.”

Anderson finds diverse iterations of ‘art photography’ in the exhibition: archetypal Modernism as practised by Max Dupain, Olive Cotton et al; the photographer as artist/anthropologist, slipping into photo-journalism (Sue Ford, Micky Allan, Ponch Hawkes); and more conceptually-based work (Tracy Moffatt, Julie Rrap, Anne Zahalka). While the dialogue around the exhibition positions photography as new kid on the Australian art scene, Anderson posits that conceptual photography “has been at the leading edge of contemporary art practice in recent times, rather than at the margins.”

Writing about a symposium on the history of photography held at the Art Gallery of NSW in May 1998 [Shadow pictures, words of light, RT 26, p 46], Cassi Plate considers photography’s plurality of discourses: “…one of the organisers, Helen Grace, pointed out that at the last event of this kind in the 80s, photography was discussed strictly within art discourse and that now it clearly exceeded this ‘connoisseurship of art history,’ drawing instead on a richer mix of anthropology, media and cultural studies.”

Continuing this theme of photography’s multifariousness, in 2001 Mireille Juchau addressed two major photographic exhibitions in Sydney — Veronica’s Revenge: Contemporary Perspectives, at the MCA, and World Without End: Photography and the 20th Century at the Art Gallery of NSW [Veronica’s revenge and Judy’s dream, RT 43]. Here more than ever, the many guises of the medium are displayed, from the extravagant postmodern roleplaying of Cindy Sherman and Yasumasa Morimura to the explicit, intimate — yet contrasting — photo essays of Nan Goldin and Larry Clark. “Goldin’s work has all the tender empathy that Larry Clark’s Tulsa (1968-71) lacks in its frank sequence on heroin addiction.”

The transformation of photography by digital technology is touched on in 1997 and 1999 reviews by Jacqueline Millner of two exhibitions by Robyn Stacey, an Australian photomedia artist who “pioneered some important trends in the field” [Lush life, RT 17, p 34]. In the 1997 article [Artificial blooms, animated stills, RT 32, p 40], Millner highlights the blurring of the artificial and the natural in Stacey’s botanically themed exhibition, Blue Narcissus: “Stacey’s images are digitally manipulated, abstracted from the ‘natural’ to varying but unspecifiable degrees. While recognisable as flowers, these images may well have been entirely generated by a computer program (although we are told in Stacey’s program notes that many derive from the scanning of actual flowers). The animation of her creations by means of lenticular screens further complicates the distinction between the natural and the artificial, the living and the dead.”

The digital takeover of the medium is specifically tackled in Mitchell Whitelaw’s review of Tekhne, the August 2000 edition of Photofile magazine exploring the transition to digital technologies in contemporary Australian photomedia [Post-photographic Photofile, RT 41], while the impact of rapidly changing technology on Australian photomedia schools is examined in Mireille Juchau’s interviews with Australian curators and teachers in RealTime’s 2003 education feature [The adaptable, ethical artist-technician, RT 56].

The ethics and the psychological power of photographic representation comes into reviews of portrait and body-focused exhibitions. Virginia Baxter is both impressed and discomforted by Ella Dreyfus’ Age and Consent [RT 30, p 43], an exhibition focusing on the naked bodies of women in their 70s and above, some taken in aged-care facilities. And following a night viewing of historic crime scene photographs curated by Ross Gibson and Kate Richards at Sydney’s Police and Justice Museum, as well as having seen Denis del Favero’s large-scale installations titled Yugoslavian War Trilogy [Did we dream this? RT 34, p 32], Baxter and RealTime co-editor Keith Gallasch find certain images seared into their subconscious: “the photographs, in their simplicity and their immediacy, are scanned onto your wetware and over the coming days they’re impossible to delete. An uneasy feeling follows you about, like the day after you dream that perhaps you’ve murdered someone, that somehow you’ve been implicated…you are complicit.”

In her response to Telling Tales: the child in contemporary photography, a group show including work by Polixeni Papapetrou, Tracey Moffatt and Bill Henson among others [The child photographed, the child apart, RT 39, p 9], Zsuzsanna Soboslay picks up on the strange ambiguity that can result when children are captured behind the lens: “The camera, identified as anything from a tool of policing (Sontag, Foucault), to one of democracy (Bourdieu), is often laid open to accusations of veiling its interpretive manipulations under the guise of objectivity.”

Interfaces: painting and screen

Two significant trends in the early 2000s owed a debt to photography: the burgeoning of video art and the rise of postmodern figurative painting. Both movements were characterised by the influence of different media and the sense that the barriers between mediums were becoming less rigid and defining. As Darren Tofts noted in RT 63 [2004: unexpected innovations], “Screen-based media art and painting might not occupy the same physical space, but in 2004 they certainly occupy the same conceptual space, in conversation with, and informing, one another.”

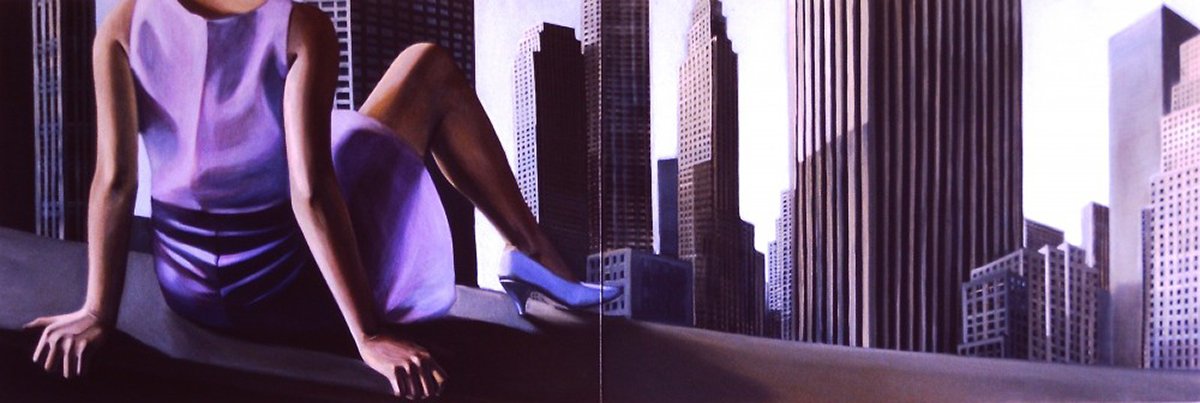

In November 2000 [Against the wall: the art of Anne Wallace, RT 39, p 41], Maryanne Lynch interviews the painter about her somewhat lateral relationship to the precepts of figurative art and the very act of producing paintings, on the occasion of Wallace’s survey show at Brisbane City Gallery. Striving for the jewel-like colours of Hitchcock’s Vertigo and The Wizard of Oz, Wallace’s still, disquieting images draw heavily upon reference photos. Viewing oil painting as “the closest thing to a pure commodity these days and therefore totally kitsch,” she seeks to create “something that is almost like an alien infestation, an alien occupation, that takes over the painting.”

Interestingly, in 2002 both Maryanne Lynch and Anne Wallace appear together in a portmanteau exhibition at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art, also featuring mini-solo showings by Anne Zahalka and Annette Bezor [Film thematic at IMA, RT48]. Though the shows are ostensibly discrete, reviewer Barbara Bolt finds Lynch’s short film Pyjama Girl, in a nice example of the slippage between different art forms, “had escaped the confines of the projection room and implicated itself in the life of the other work.” Bolt recalls “Zahalka’s light box images of Sydney became more alienated and Wallace’s paintings attained a state of high anxiety.” She aligns Wallace’s work with film noir and sees in it an unfolding drama.

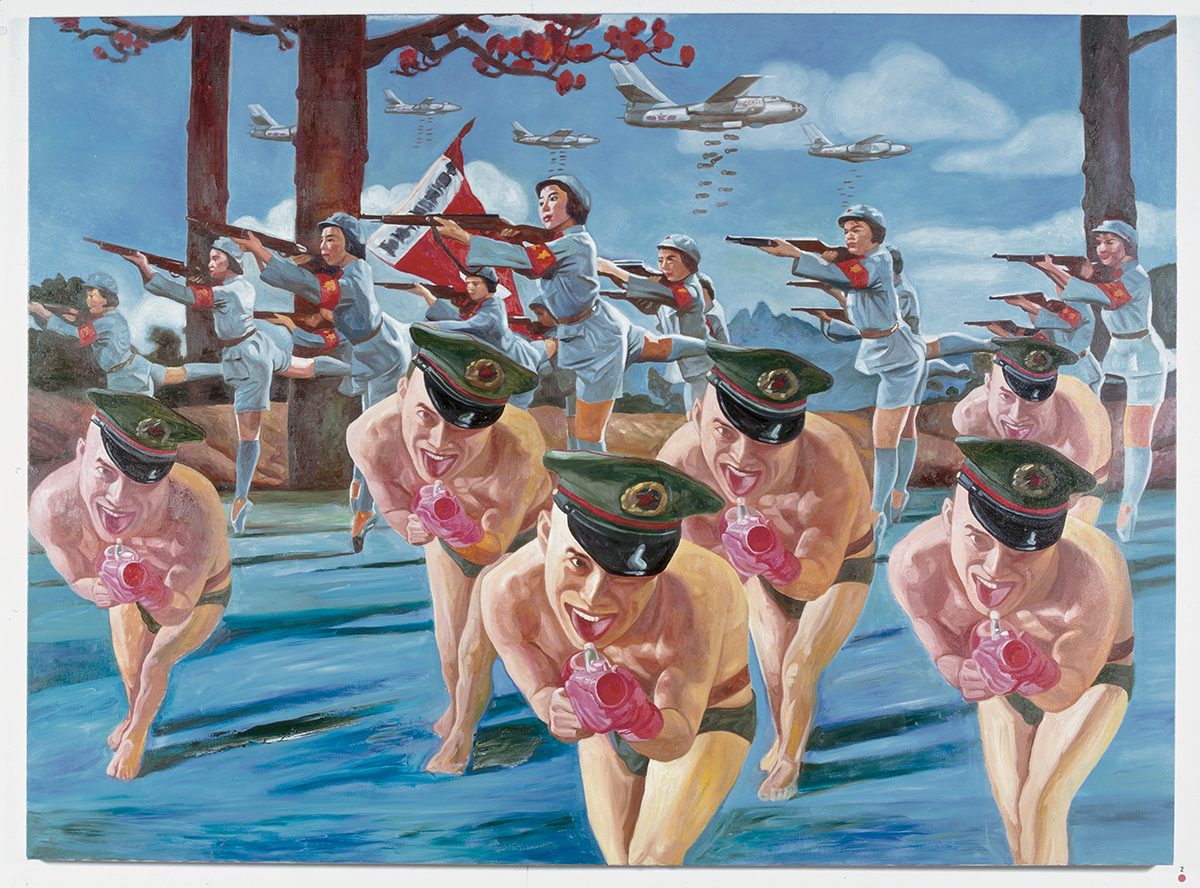

Painting flourishes within RT 42, beginning with pieces by Linda Jaivin [Liberating the artist from the revolution] and Trevor Hay [Sex, drugs and revolutionary ballet] on the Chinese counter-revolutionary Pop art explosion as exemplified in the work of Chinese-Australian painter Guo Jian. Further on, Chris Reid looks at Painting, the Arcane Technology [Reinvigorating the arcane], an exhibition of 12 Australian artists, whose curators Natalie King and Bala Starr note a resurgence of painting “after the 1990s infatuation with installation art, object-making, photography and multimedia practices.” The exhibition offers further evidence of cross-pollination of artforms, with the catalogue acknowledging “the influence of new media — cinema in the case of Wallace and Louise Hearman, photography in the case of David Jolly.”

Lily Hibberd, Blinded by the Light, 2002, reproduced on the cover of RealTime #57 courtesy of the artist, Art+Film exhibition, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne

To round off the painting/screen culture nexus, the paintings of Lily Hibberd are singled out by Daniel Edwards in a review of the multidisciplinary exhibition Art + Film at the Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP), examining cinema’s infiltration of contemporary Australian art [The art of in-between, RT 57]. “The oil and phosphorescent paintings captured the hypnotic illumination of the cinema screen, as well as cinema’s reliance on the ephemeral qualities of light to bring its images to life. More crucially, at the level of form and content, these two paintings illustrated the concerns running throughout Art + Film.”

Video art rising: the body, the everyday

RealTime’s documentation of a decade of flourishing video art evidences a form every bit as diverse as photography, ranging from grainy anti-aesthetic VCR pieces to the grandiose visions of Bill Viola and Lyndal Jones. In 2003 [Video goes big time: some crucial questions, RT 56], Blair French provides a terrific overview of the form, from its roots in experimental film to the great scope and variety of contemporary practices, and usefully wonders what critical approaches are best equipped to deal with such formal and conceptual diversity – something further complicated by video’s ubiquity outside of the art world. It’s a great reference for anyone seeking to grapple with what precisely constitutes video art.

In 1999, Edward Scheer is impressed by the power of work by four major women video artists in The 5th Guinness Contemporary Art Project, Voiceovers, at the Art Gallery of NSW [One day all headstones will be electronic, RT 34, p 13]. Works by Nalini Malani, Shirin Neshat, Mariko Mori and Lin Li produce an empathetic response that signals video’s potential to “effect the rescue of our tired media and our exhausted senses and re-humanise aesthetics as an experience of the body.”

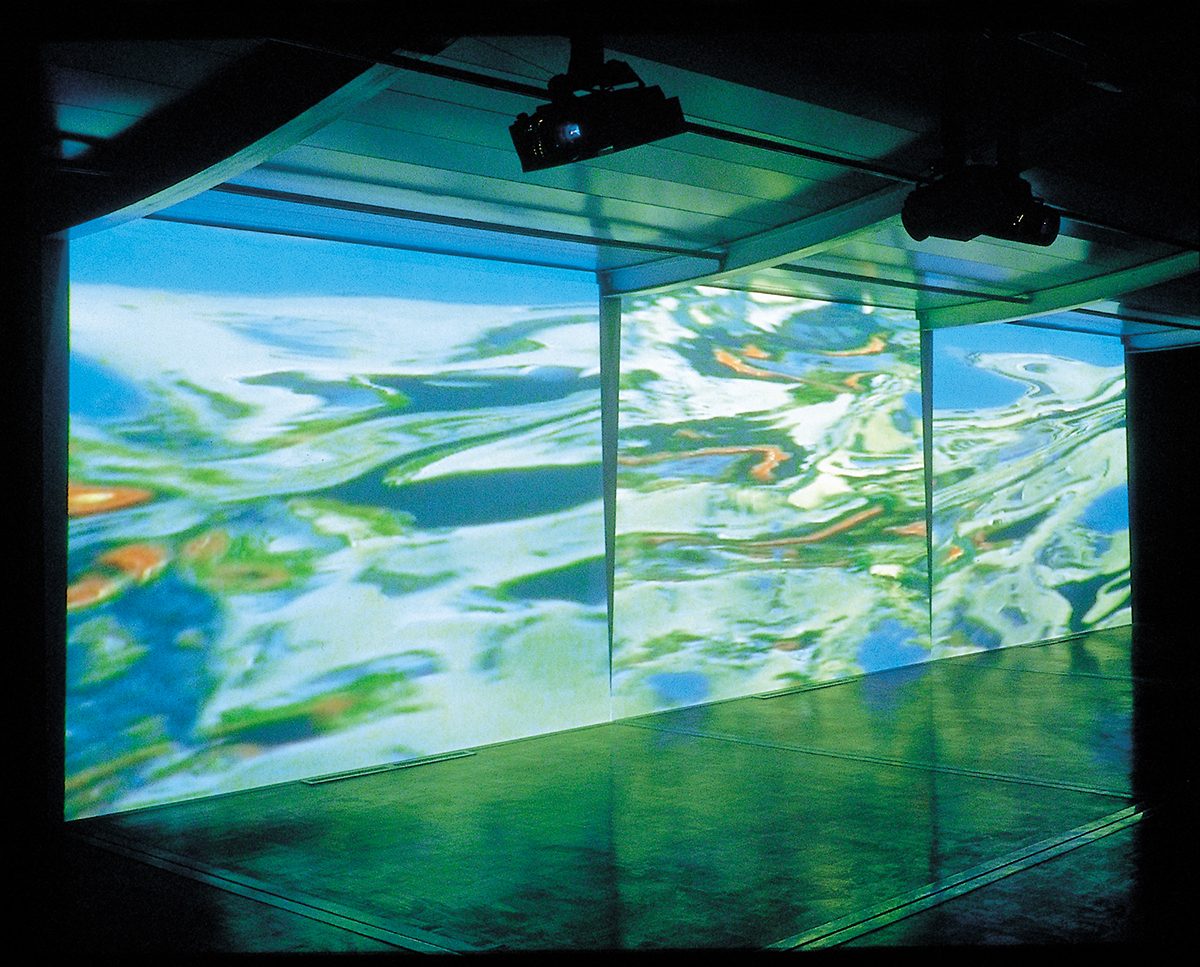

Bec Dean’s experience of Bill Viola’s installation The Messenger, viewed on this occasion at St George’s Cathedral, and The Interval, at John Curtin Gallery – both part of the 2000 Perth International Arts Festival – is of immersive work that knowingly deploys Renaissance pictorial conventions and the symbolism of religious architecture to “force the body into feeling” [Perth Festival: breaking surfaces, RT 36, p 7]. An interview with Lyndal Jones on her work Aqua Profunda, representing Australia at the Venice Biennale [Aqua Profunda: art in the deep end, RT 43], reveals a similar desire to immerse the viewer: “I work with video from a subjective, experiential position for the viewer. Consequently, a certain type of critic has difficulty with it because they can’t stand outside it and analyse it. But for a lot of people just watching it, it’s quite straightforward. They’re just in it.”

At CCP’s installation of David Rosetzky’s standardised set of video confessionals playing with both banality and intimacy, Ned Rossiter is another RT writer prompted to assess the emotive power of video art [Custom made confessions at CCP, RT 38, p 35]. The simultaneous artifice and directness of Rosetzky’s work raises a question about what factors make a filmed confessional credible. Undercut by the instability of their display (fleeting projections on cheap wood veneer), the earnest monologues suggest “our sense of reality is constituted precisely in the refigurings we make of mediatised commercial culture.”

Writing in 2004 about video works “bridging the worlds of art and daily life” [Video, medium of the moment, RT 62], Rachel Kent unequivocally positions video bang in the centre of Australian contemporary art practice after a decade of significant employment – a decade that fortuitously coincides with RealTime’s own first 10 years. She considers two Sydney exhibitions: Mix-Ed: diverse practice and geography, at Sherman Galleries, and Interlace at The Performance Space. In Mix-Ed, she finds emerging Australian video artists (Emil Goh, Shaun Gladwell, Daniel Crooks, Daniel von Sturmer) making a kind of poetry from the everyday, urban environment, and in Interlace (featuring Goh, Gladwell and Kate Murphy), the “role of performance in daily life is a recurrent theme.”.

Kent also mentions video’s propensity to absorb other artforms: “Drawing upon conventions of documentary and portraiture, and referencing art history as much as cinema and pop culture, [these works] bring the city and its inhabitants to life in often unexpected ways.”

The art experience captured in words

As I wind up this overview, having looked at broader trends and scholarly surveys, it would be remiss not to mention RealTime’s attention over the first decade to small, off-beat exhibitions, which it approached through a range of personal, equally idiosyncratic responses.

Virginia Baxter’s reviews are characterised by an elegant, experiential quality that’s wittily evocative. Her 1997 [RT 19, p 14] response to Incognito, an exhibition of women installation artists, is a sort of dance through the Performance Space Gallery, tracking the movement of her body, eyes, feet as she’s alternately drawn to one work before being distracted by another. “Suddenly someone else enters the room. Caught screen hogging, I scramble up from the floor. Is that the time? Easily an hour has passed. I scuttle backwards through the exhibition, nodding to the coloured messages, still pulsing a pink ‘Don’t’. Darting a parting glance at the still jumping girl with the fans, hair flying, I fall into the street.” The experience is indivisible from the artwork, and the review is richer for it.

Linda Marie Walker’s elaborations on Rick Martin’s Maria Ghost [RT 23, p 31] and Jonathan Dady’s Construction Drawings at CACSA [So close to the thing itself, and not], are little artworks in themselves; text-based analogues of the original installations. Her meditation on drawing in the latter review could apply equally to her reviewing: “Is drawing an after-effect in its own right? Does a drawing make its subject (overall) a completely different thing (?) — a thinking thought-of thing, a point of transition, from which it desires to be the effect of ‘afterwards’; after-the-fact of presence comes another presence (over and over) from which the thing cannot recover, it’s there ‘anew’, however slight the change might be —perhaps changed only by acts of thought.”

In a similarly inventive way, Russell Smith approaches Shaun Kirby’s installation Gasfitter [RT 39, p 43] as a list of clues through which one might decode the artist’s “minimal”, “signlike” objects. “Like words they’re empty, arbitrary, and meaningless as things-in-themselves, intelligible only through their relationships. But rather than the jokey challenge of the riddle, Kirby’s is the creepy syntax of the enigma.”

Demonstrating the stylistic possibilities of arts writing, these lively snapshots join RealTime’s bigger-picture analyses to form a considerable breadth of visual arts coverage, affording readers the opportunity to delve deeply, gaining an insight into movements, mediums and makers; and a vivid sense of the cultural landscape of the time.

–

RealTime Assistant Editor Katerina Sakkas is a Sydney-based writer and visual artist. You can read about her here.

Top image credit: Springtime, 1999, Anne Wallace, courtesy the artist