Wheatbelt town goes global

Sarah Miller: Shigeaki Iwai, IASKA

Shigeaki Iwai, a shot of Kellerberrin #5/8

Somewhere between Perth and Kalgoorlie lies the small wheatbelt town of Kellerberrin, home to the International Art Space Kellerberrin Australia (IASKA). On a glorious spring day in 1999, I drove to Kellerberrin with Japanese artist Shigeaki Iwai to check out both the art space and the town. The day was full of colour: red roadside dirt, vast blue sky, pink and white paper daisies and the blinding gold of canola fields in flower.

At times, the canola fields stretch past the horizon, bending your eyeballs and doing very weird things to your sense of space.

IASKA is housed in the main street of Kellerberrin. Arriving at midday, we could see precisely 2 cars, one sleeping dog (of course) and no people. Now, city girl that I am, I am at least familiar with the concept of space and country. I can’t imagine what it might mean for an artist from megatropolis Tokyo, a city of 37 million people, to encounter that landscape, let alone spend 3 months in a tiny community with a population of 1000 (including the surrounding district). Nevertheless, in 2001, Iwai, his wife and 3-year-old son, did just that. His exhibition Could you guide me around, ‘cos I’m just tourist from Japan was the outcome of that residency.

Iwai’s project for IASKA , sometimes funny, often poignant and always moving, gently and perceptively opened up a space of engagement between the local and the global, an interface between community and conceptual practice. The exhibition might be described as a town portrait in 3 parts—a conceptual triptych.

The first part consists of a series of 8 postcards, each identified only by edition number as “a shot of Kellerberrin” and carrying the words, Imagine…now you are in a tiny wheatbelt town in Australia. A single postcard was sent to about 100 people in Japan, Europe and the US. No other information about the place or the people was provided. Fifty postcards commenting on the images were returned for installation in the gallery.

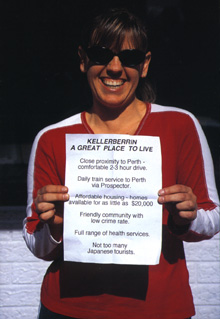

Before Iwai’s arrival, the town only had one postcard—a picture of the post office. Conversely, Iwai’s images, like those of most tourists, document his rather more personal ‘monuments’, images that provide a key to his growing sense of place. They include: a view of the town from its only ‘lookout’—the country is unbelievably flat; sunrise over a shearing shed; a moody night-time image of the old deco-style cinema (now closed); primary school children in yellow t-shirts and blue trackie pants; derelict cars rusting in a paddock; an Aboriginal grave-site with plastic flowers, incense and small statuettes of the Virgin Mary; a portrait of Noongar elder Cath Yarran with her sister; and a smiling Australian woman holding a photocopied sheet containing salient facts about Kellerberrin.

The responses to those images suggest that many people view Australia through the filter of a 1950s B-grade American western. Some respondents seek out similarities to their own place while others struggle with the unknown. Some are friendly. A couple are antagonistic. Whilst one Japanese recipient was amazed by a place with so much space you could leave cars to rot in a field, a Dutch correspondent was appalled by this clear ‘evidence’ of violent Australian men who drink too much, concluding, “I NEVER want to go there.” Ironically, I find myself feeling a little defensive.

Iwai’s research also consisted of 20 interviews with local people. Rather than transcribing, he wrote a subjective response to the experience of those intensive interviews undertaken with (for instance) a local doctor, a farmer, a Noongar Elder and a retired Italian construction worker. For the third component of the exhibition, Iwai borrowed a representative chair from each subject. Each chair—centrally positioned in a circle in the space—was draped in red fabric onto which Iwai had screen printed unidentified verbatim quotes from the interviews.

Returning to Kellerberrin for Iwai’s opening, I discover that not only the gallery but 2 other shopfronts have been taken over (at least temporarily) by Perth-based artists Philip Gamblen, Brigitta Hupfel and Andrew Smith, who participated in a week long workshop with Iwai. The next day I hear about the performance area planned for a salt flat on a property just west of Kellerberrin, while others are mulling over the possibility of re-opening the old cinema. In the front window of the IASKA space, slide projectors are flicking through images of Kellerberrin and Tokyo, while in the gallery the audience of mostly local residents are doing the opening thing—drinking, chatting, looking, reading and having a whole lot to say about the exhibition and their roles within it. As dusk falls, I experience a kind of epiphany: imponderables like ‘arts led recovery’, elitism, community, space, conceptual art, cultural exchange, centres and peripheries, and Japanese tour guides with little coloured flags flicker through my consciousness. I seem to have landed in ‘Art Town Kellerberrin: a great place to live’.

Shigeaki Iwai was IASKA artist in residence, June-August 2001; exhibition: Kellerberrin Gallery, August 4-September 2. A publication from his residency is forthcoming.

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 27