womadelaide: art, action & erasure

benjamin brooker: interview, luc amoros, blank page

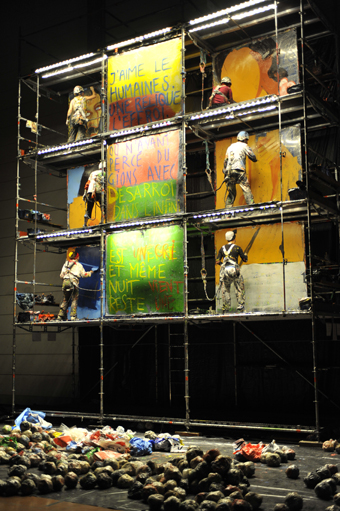

Blank Page, Compagnie Luc Amoros

photo Philippe Gisselbrecht

Blank Page, Compagnie Luc Amoros

THE BLANK PAGE HAS LOOMED LARGE IN THE WESTERN IMAGINATION SINCE THE ARRIVAL OF THE GUTENBERG PRESS, A SYMBOL BOTH OF LIMITLESS POTENTIAL AND THE VAGARIES OF THE CREATIVE MIND: A NOVEL OR ESSAY ABOUT TO BE BEGUN, THE CRUSHING EMPTINESS ENGENDERED BY A BAD CASE OF WRITER’S BLOCK. THE BLANK PAGE MAY ALSO CONTAIN A SECRET HISTORY, LIKE THE PALIMPSESTS OF THE ANCIENT GREEKS AND ROMANS, WORDS AND IDEAS OF OTHER TIMES AND OTHER MINDS HAVING BEEN SCRATCHED OR SCRUBBED OFF TO MAKE WAY FOR THE NEW.

The 2013 WOMADelaide festival will feature French company Compagnie Luc Amoros’ multidisciplinary performance Blank Page (Page Blanche). Nine revolving Perspex screens housed within a 10×10 metre scaffold provide the performance’s tabula rasa upon which six actors create an ever-changing series of words and pictures. Up to 300 kilograms of paint are used in one hour as the kaleidoscopic procession of images and disembodied phrases evokes the work of Gauguin, Van Gogh and Warhol, the Altamira cave paintings, graffiti and propaganda art. No sooner has one image emerged than another has been wiped away with kerosene, the panel then painted black in preparation for a new pictogram or a statement, perhaps one like this: “The world only exists if it is painted and sung.”

The performers not only paint, but interact through song, chant and dance with a part live and part pre-recorded soundtrack which features electric and double bass played onstage. There are traces, in Richard Harmelle’s soundscape, of Arabic chants, African rhythms and the music of the Polynesian islands.

Company founder Luc Amoros says that the music in Blank Page is “more about a musical translation than a simple accompaniment.” It is all part, he explains, of an attempt to create what he calls “a living stage,” a street space—never a theatre—in which a sort of alchemical meeting of the written, visual and performed arts can take place before an audience who never quite know what to expect: “A street is less cramped than a room. There are other dimensions there. The gaze of the spectator is not necessarily the same. In the theatre, the spectator expects something; in the street, anything can happen.”

Amoros, unable to abandon the metaphor of the book despite Blank Page’s sinuousness of form, says that the show moves through five distinct though disparate “chapters”: “the aesthetic universes of the ancient Mayan and Aztec civilisations; the birth of the painting and, with it, the self-portrait; the everyday poetry that has developed among the people, such as Brazil’s Cordel street literature [inexpensive publications often in verse. Eds]; Hiroshima and the Holocaust; the painting of Paul Gauguin.” It seems just as likely—and Amoros does not reject this—that audiences will see gestures towards other stories in the work. It is difficult, for instance, not to be reminded of the transient words and images which once adorned the Berlin Wall, or that now appear as rejoinders to the injustices of partition and dispossession upon the bricks of the West Bank barrier.

I put it to Amoros that Blank Page is a performance that seems as much about loss as creation, about the Orwellian destruction of history and language. “It’s about people and languages,” he tells me, “languages that nobody speaks, that are lost forever. Those which are still alive can find refuge in writing, sheltered from oblivion.” Amoros recounts the (probably apocryphal) story of Humboldt’s parrots, the last living creatures capable of reproducing the language of the massacred Maypure tribe. “This performance speaks of nothing directly, not even Hiroshima,” Amoros says, “but we invite the spectators to reflect on the disappearance of languages.”

Luc Amoros is the author of all of the text which appears in Blank Page in a variety of languages throughout the performance. Audiences might be asked, “Sixty years after Hiroshima, how can we watch fireworks on Bastille Day?” One might just as easily enquire, “How can we go into German souvenir shops and buy pieces of the Wall?” I rephrase this for Amoros who seems reluctant to brand—if that is the word I want—Blank Page as anti-free market, a swingeing reproof of the capitalist logic which ‘ended history’ in 1989 and requires that everything, as long as it is at the right price, is for sale. Amoros says, “We make images on the stage to provoke and to preserve. We do not sell them, as is the case with most images we are faced with today. Compared to cinema, or the visual arts, our speciality is a direct, physical relationship with the public.”

WOMADelaide: Compagnie Luc Amoros, Blank Page, design, text, staging and images Luc Amoros, music Richard Harmelle, Botanic Park, Adelaide, Mar 8-11; www.womadelaide.com.au

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 42