word magic: the how of reading

tim wright on the electronic literature collection

Rainer Strasser and MD Coverley’s ii—in the white darkness

IN ONE OF THE KEYWORD DESCRIPTIONS BURIED WITHIN THE ELECTRONIC LITERATURE COLLECTION THERE IS A SENTENCE WHICH I THINK SHOULD APPEAR AS A WARNING BEFORE ALL ATTEMPTS TO DEFINE ELECTRONIC LITERATURE: “WRITING NATIVE TO THE ELECTRONIC ENVIRONMENT IS UNDER CONTINUAL CONSTRUCTION (POIESIS) BY ITS CREATORS AND RECEIVERS.” THIS COLLECTION IS SO LARGE AND HETEROGENOUS THAT IT IS ALWAYS ONE STEP AHEAD OF ATTEMPTS TO DESCRIBE IT.

There are 60 individual works here, many of which you could spend over an hour with. Most kinds of e-lit are represented: hypertext writing, kinetic poems, codework (writing which incorporates programming languages), interactive works, as well as expanded forms of the traditional genres of fiction, poetry, memoir, comic, and non-fiction. Early exponents of the form such as Shelley Jackson, Phillipe Bootz, and Talan Memmot are represented alongside lesser known writers. Helpfully, each work is tagged with keywords, allowing the reader another way in to what is a daunting amount of material. The subjects are often imaginative, from an exploration of the connections between concrete poetry and subliminal advertising to an interactive graphic based on a story of demonic possession. Across the works there are themes which recur: an interest in systems and viruses, in memory, and in the process of translation and recombination.

People tend to read more distractedly on the internet than they do in print. Intentionally or not, the writers and artists counter this tendency in different ways. In some of the interactive works the response time is slower than broadband users have come to expect (that is, not instantaneous) forcing the reader to slow down and enter the work rather than wildly clicking to get to the “end.” Others exaggerate this tendency towards distraction by throwing at the reader more information than they can process at once. Generally, the pieces are as much about how you are reading as what you are reading.

Rainer Strasser and MD Coverley’s ii—in the white darkness: about [the fragility of] memory visualizes the experience of memory in people with diseases such as Alzheimer’s. We see a gauzy white curtain with shapes of light wobbling on it, and behind this a blurred sky that could be dawn or dusk. The image appears drained, somewhere between a photograph and a watercolour. Across this curtain a pattern of perfect white circles pulses. Clicking on them makes stark images appear: a canal, a wooden walkway, a crisp blue square of swimming pool water. Occasionally fragments of text appear. Sometimes parts of images bob at the bottom of the frame, frustrating the reader who is unable to decode them. The work responds slowly to reader input, mirroring the experience of trying to recall a memory that has been misplaced or distorted.

Jean-Pierre Balpe ou les Lettres Dérangées by Patrick Henri-Bergaud is what typographers see when they close their eyes after a long day. Within a black and white interface that mimics a page of print, serifed letters sit across the screen in the shape of a poem with most of its letters missing. Other letters drift around the screen in determined courses, spinning and swivelling until they catch on another nest of letters. Minute movements of the mouse dislodge the letters from their position, and they spin off again in various directions. Suddenly the mouse is energised, tense with potential; I nudge it along with two fingers as if it were an egg. The screen itself starts to seem delicate; I realise that if I banged my desk with my fist it would disturb the mouse enough to send the letters cascading. The “aim” of the work is to rebuild the poem by putting the letters in place, yet after twenty minutes trying I was no closer to doing this, and possibly further away.

Mary Flanagan’s The House, built with an open source programming language, Processing, is digital as it was once thought of: crystalline and inviolate. We see a cluster of cubes and three-dimensional lines from a poem; zoom in and you are inside the transparent structure, zoom out and it resembles a model of a chemical compound. As the reader turns and rotates the structure the lines of the poem change. Contained inside a small square roughly a quarter the size of the screen, it is an intentionally claustrophobic work, reflecting the stuck nature of the relationship talked about in the poem.

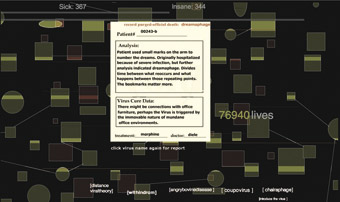

Jason Nelson’s Dreamaphage

Poet and digital artist Jason Nelson’s aesthetic is the opposite. Poem fragments and chopped up, scanned pictures from old science textbooks float through his works like space junk or objects in dreams. In the two drafts of his 2004 work Dreamaphage included here, he explores the equivalences between viruses and dreams. The reader seems to fall into the work, passing books whose pages can be turned and read by clicking and dragging the mouse. Nelson’s magpie approach to words, pictures and sounds creates an immersive, authentically strange world.

Perhaps the most recognised form of e-lit is hypertext. Shelley Jackson, the author of the early and influential 1996 hypertext, Patchwork Girl, is represented here with her hypertext memoir from the following year: my body, a Wunderkammer. The first thing we see is a lino block print of a female body divided into sections that link to different beginnings to the story. The interface is simple—once you are inside it is mostly text—leaving the lucid prose free of distractions. Jackson’s memoir shows that hypertext, with its fluidity and the way it compels the reader to move laterally across a work, is well suited to writing memory and

history.

Maria Mencia’s Birds Singing Other Birds’ Songs

Maria Mencia’s Birds Singing Other Birds’ Songs uses thirteen separate looped birdcalls which the user can switch on or off to create and oversee their own soundscape. Along with a birdcall each button releases a calligramme bird, which flies back and forth across the screen in a vision that would have made Apollinaire swoon. It is a gorgeous work. William Poundstone’s Project for Tachistoscope [Bottomless Pit] is not gorgeous, from the difficulty of actually watching it to the unfashionably loud colours of the interface. The central idea explored in an essay within the work is the fact that subliminal advertising and concrete poetry were invented at the same time in the early 1950s. The work itself is a digital version of the tachistoscope—a machine which flashes projections at a specified speed, often used in market research to test image recognition. Viewing the work feels like undergoing a kind of Pavlovian conditioning experiment; the eyes are constantly recouping, trying to stabilise a relentless, strobing afterimage.

One of my favourite works is Reiner Strasser and Alan Sondheim’s Tao. A poem of less than twenty words scrolls across the screen like a news bar below two looped shots of a road and a mountainous landscape slipping by outside a car door. It is a momentary work, all over in 38 seconds. The different elements—cinematography, interactivity, poetry, and soundtrack—are combined as subtly and carefully as those of a Zen garden.

The editors have stated that one of the purposes of putting the collection together was to expose the work to people who may not have seen it otherwise. To this end, a CD-ROM of the collection was produced—available free from the publishers—in addition to its online publication at http://collection.eliterature. org/1/. Licensed under Creative Commons 2.5, which allows it to be copied and shared, their hope is that libraries and schools will install it on their computers, teachers will use it in lessons, and people will share it among their friends. In the breadth of work contained in it, as well as the innovative way the editors and authors have made it available, this is a generous collection.

Electronic Literature Collection, Volume 1, editors N Katherine Hayles, Nick Montfort, Scott Rettberg, Stephanie Strickland; published by the Electronic Literature Organization, October 2006http://collection.eliterature.org/1/

The Collection includes works by Australian artists Melinda Rackham and geniwate.

RealTime issue #78 April-May 2007 pg. 28