Writing the art experience: Itching shaking crying being held – Part II: On vulnerability

Threshold 1 (ageing):

Justus Neumann’s Alzheimer Symphony (2016) cuts to the heart of what we fear as we emigrate from one part of our lives to another — in this instance, crossing into old age and forgetfulness. For what is the value of a man, when his mind slips, his memory sags, his world becomes a cage?

The protagonist of Alzheimer’s Symphony is both King Lear, mad on the moors, and Vladimir (or is that Estragon?) in Waiting for Godot, but he is also, brilliantly and painfully, an ageing Neumann, contemplating his inevitable decline. As we do ours, in watching.

Despite the smell of on-stage cooking of toast, and eggs burning in overheated oil, his Shakespearean “Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks” is electrifying. Grasping for mnemonic objects such as a hairdryer and balloons (representing wind and cheeks respectively), he crows, “I can do it; I can still do it,” with desperate bravado.

Justus Neumann, Alzheimer Symphony, photo courtesy the artist

But as the piece progresses, and such mnemonics fail, we are left with the enactment of a concrete poem of spatula, eggs, balloons, photographs and the wrinkles of Neumann’s face, shifting and re-forming like seismographs of a life still worth living. These, however, constitute an alternate, and alternative, virtuosity.

Threshold 2 (soporifics):

Trevor Patrick in Wendy Morrow’s Sleep (2002) hangs, suspended in a space between walls (where two walls fail to meet, or have just parted). There is an illumination from behind his body – in this gap, from whence he’s come. His bony cheek rests against an edge. Is this the beginning, or the end, of his life? Is this — the in-between (sifting, sorting, re-conditioning our worlds) — the more real (world), that needs our attention?

Amongst all my comings, doings, namings, is this piece (of dust, to which we all return) the most important one?

Threshold 3 (a very particular dream):

In London with RealTime for LIFT (London International Festival of Theatre), 1997. In Queen Elizabeth Hall for Saburo Teshigawara’s I was Real-Documents. Dusk. A terrace, a dusk that crawls. The parterre moves; furry figures rearrange themselves. Night birds crackle; wings stutter. A trumpet sounds a modal corridor. Four men enter, soundlessly, bend down to pick up soft sailor hats. They wear them, remove them, exit silently. They are hardly here, have hardly been. One; two; three more. One; then three more. Night slides further in.

This bending (to retrieve, then disappear) becomes a motif: to enter and to bend is an honouring. They are supplicant: remembering a meaning. Pate vulnerable, neck low, laid bare to the axe-man. To whom is this sacrifice laid bare.

And I am here. Where are we, collectively. Is this, or not, my own dreaming.

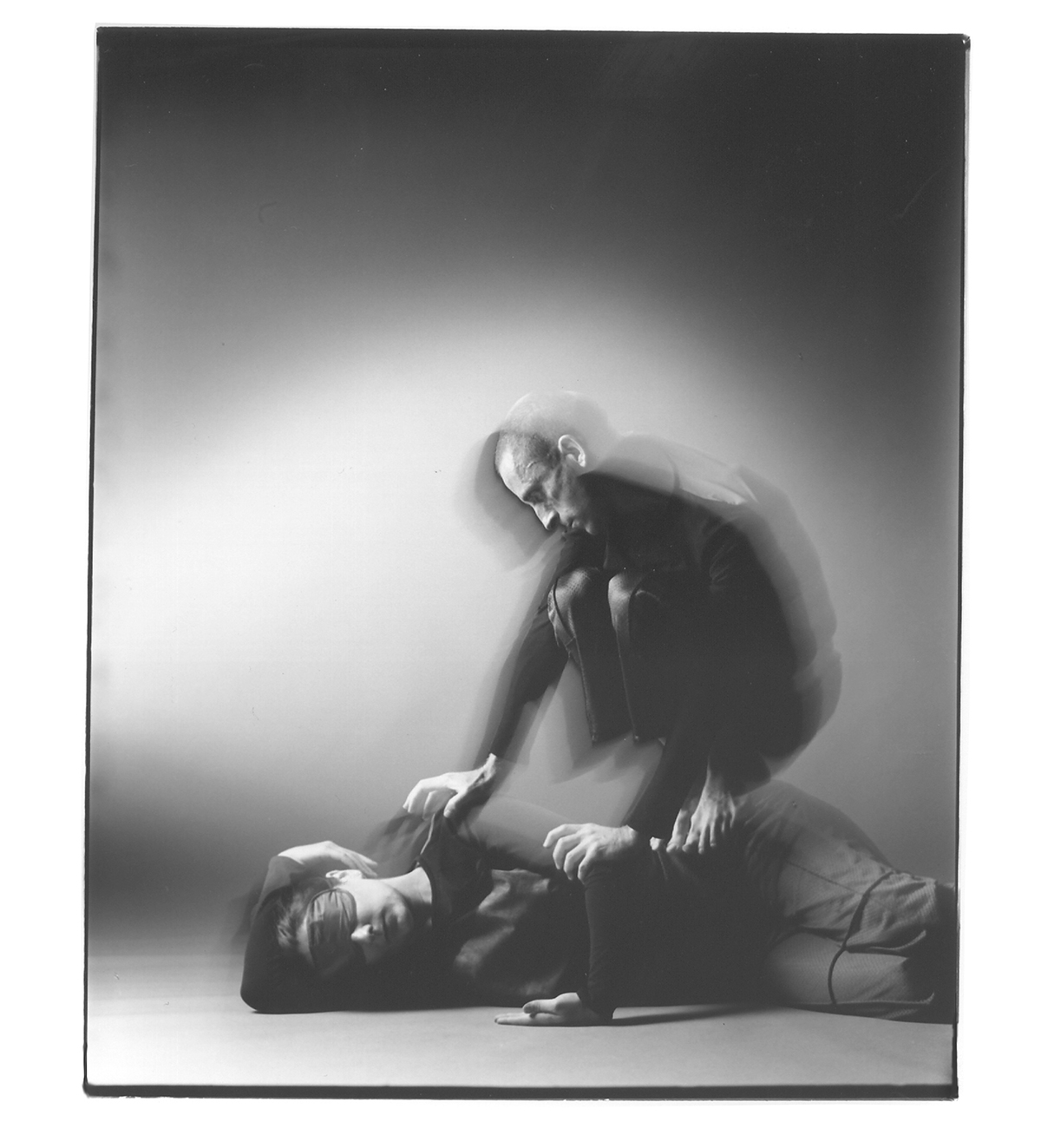

Rebecca Hilton, Trevor Patrick in Lucy Guerin’s Heavy, photo Ross Bird

Threshold 4 (measurement):

Lucy Guerin’s Heavy (1998) challenges me differently, with bodies slipping, dissolving and then jerking half-awake, juxtaposed against the steady constant of an EEG print-out falling from the ceiling. The printout, a long and continuous cascade, is science-as-waterfall: inexorable, as is science in contemporary consciousness, asserting its measures upon us.

In the review Philipa Rothfield and I discuss the difference between representations of sleep from inside-out, or outside-in. Like a tempestuous goat, I assert: “This is not how I dream,” insisting that a dream’s slipstream can never be measured via a polygraph machine. I write:

“Touch me with silk, I will chant you my palaces. Dip me in quicksilver, I will chart you my night escapades. Knights and dreams and flossy places. I know exactly where I don’t know where I am.”

We are “the stuffings of sleep”, I say, “Shakespeare’s pillowslips.” Oh, if only — as, in years since, I have followed my two children into worlds where the black seams of sleep provide not such comforts as this. My soft poetic polluted dreams.

But, at the time of watching Heavy (cocksure) I write: “you forget the science of it, the opening night crowd of it; you see patterns (e)merge, patterns of patterns, pairings, shiftings, allegiances that betray you, or stay loyal. They are our sanity, these re-patternings, as limbs stretch and reclimb the vine and beanstalk that’s been commanded to regrow.’

At the time of viewing, “the edge of my tongue itches at a fairy-tale. A Luna Park smile appears in sinister bones.” It is now 20 years, and two children, since I wrote this piece. Do I still believe the same?

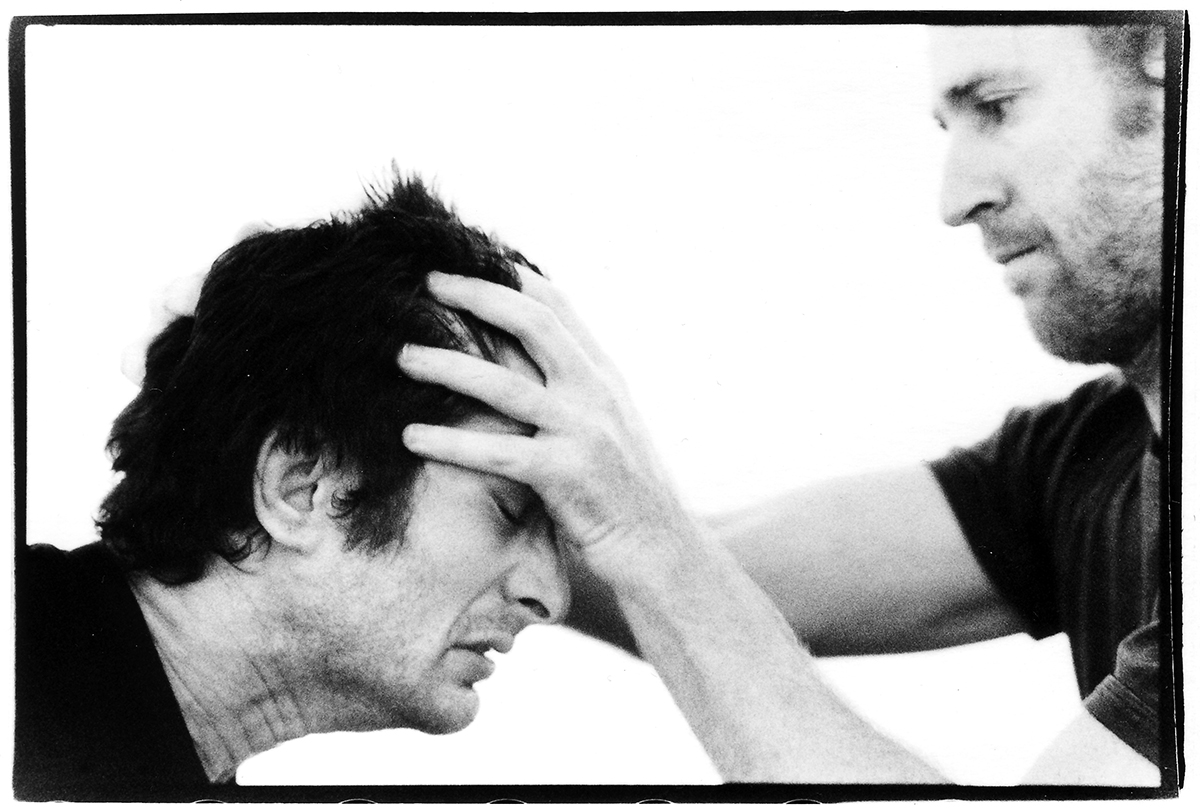

David Corbet, Jacob Lehrer, Excavate, photo by George Kyriacou courtesy Australian Choreographic Centre

Threshold 3 (digging):

During Excavate (2006) — an examination of Australian masculinity — David Corbet climbs up Jacob Lehrer’s body as if it were a mountain, or an elephant. High-seated as a rajah, Corbet blinds Lehrer with his hands, steers his face. Lehrer also self-directs, propelling the double-bodied monster into the audience. This is both filmic hyperbole, and real-time fright. An arch combination of (pro)positions.

There’s plenty of ‘men’s business’: jamming fists, noir back-alley brawls, bam, smash, pow. But what troubles me is not this overt violence [faked, though it is].

But where do these men’s hands go and not go? What and how do they not touch? What is more violent than completing a violent action? What multitude of qualities, dialogues and choices is in those hands before they smash the other player into the wall?

In a post-show forum, Lehrer dismisses (but Corbet is fascinated by) the challenge posed in these questions. So many in the audience later tell me they are so very glad I asked. It seems that near-violence touches us, so many, I had not realised quite how many. The forum’s audience seems relieved to have the questions opened, if left unanswered. Our troubled speculations go out with us, into the night.

Australian Percussion Gathering, Brisbane, 2010

Threshold 4 (silences):

Percussion performance of course requires the touch of skin, or mallet, against membrane. As does caressing, child-rearing, boxing and punch-outs.

In 2004, I witness Steve Schick perform Iannis Xenakis’ solo Psappha as if he were strung and pulled with high-tension wires. In 2010, he performs the same piece, in what he estimates is his 250th iteration. The piece still holds a violence; he kicks the side drum like a tempestuous goat, obsessive, seething. His master class at the first Australian Percussion Gathering, Brisbane, 2010 shared techniques with students, on how to help keep oneself fresh and able to surprise oneself in performance.

Schick emphasised percussion’s humble, tribal origins: the contact of skin-to-skin, hand to drum membrane, our bodies as membranes and mediators of the world. He even quietly threw the challenge to younger students to consider the shamanic origins of performance, a player perhaps passing through membranes to other or hidden worlds. This provocation matched the tone of the conference as a whole, which was remarkably uncompetitive and non-aggressive — in part, in honour of Australia’s earliest percussion mentor, Barry Quinn, who would apparently teach anyone who could throw a stick at a wall and catch it on the rebound.

But as Artaud wrote, “Being has teeth,’ and “Being” can be both encouraging and fierce. There was nothing quite like witnessing Sylvio Gualda (for whom Xenakis wrote his exacting percussion solos) demonstrate “not ffff [quadruple forte] but energy” with barely a flick of his wrists. It was like the Concorde’s sonic boom at 10 paces within two seconds (moments Corbet and Lehrer, for example, did not understand). Gualda holds this split-second ignition in his ribs. Boom Crash Kapow.

However, other acts of percussion do other things in term of bodies in place/space and membrane, potentially enacting a dialogue between our bodily fluids and the rivers, our bones and the soil formed over our lifetimes and beyond.

In a day of listening and playing in the forests of the Sunshine Coast hinterland,

“A young woman suddenly starts walking on all fours, boots on her hands (becoming animal); a senior percussionist rustles a tree (becoming mantis); two young men rumble a dying branch to its sonic death. Drums become insects and call to invisible partners across the mountainside. A song is improvised beside a Bunyip’s waterhole. Jan Baker-Finch rustles her body like leaves, moving, being moved by the winds of other improvisers.”

Threshold 5 (fireworks):

And finally there’s another side, to the impact of performing, making, being seen. Boom Crash Kapow. 1997 London International Theatre Festival: Christophe Bertonneau’s Beautiful Violence: Un Peu Plus de Lumiere (a little more light) in Battersea Park. I write for RealTime:

“Every time I see fireworks, I remember Guy Fawkes, who tried to blow up British Parliament in 1605… I have a suspicion of spectacles. All the marshalling of forces and finances, titillating toy wars removed from the battlefields. Guy Fawkes was a thug, an extremist, a separatist, celebrated annually in a fizz and pop night with various safeguards (in Australia now, illegal in one’s own backyard).

“At LIFT’s fireworks, torches spiralled in the sky. We are in Vietnam with napalm, London with firebombs. Is it the shape of the burning dragon that appeases us? The ground-level ritual most of us couldn’t see, an attempt to change meaning/appease us with paper baubles? Am I just a killjoy?

“No, of course, I too gawped and craned and wondered how much further they could go, how much higher, brighter, more audaciously changing night to day (as do poets and lovers, more frequently, cheaply, intimately), but this is awful and aweful, the crowd impatient with the in-betweens and jeering and leering and panting for the explosions once more. Our public hangings now going off with a bang.

“We are cruel masters and cruel livers; we beat dogs and wives. Fireworks express and contain our violence, colouring in hues that make the skies incarnadine or dappled green or white like stars that couldn’t possibly cluster as closely, brightly. It is very strange to be here.”

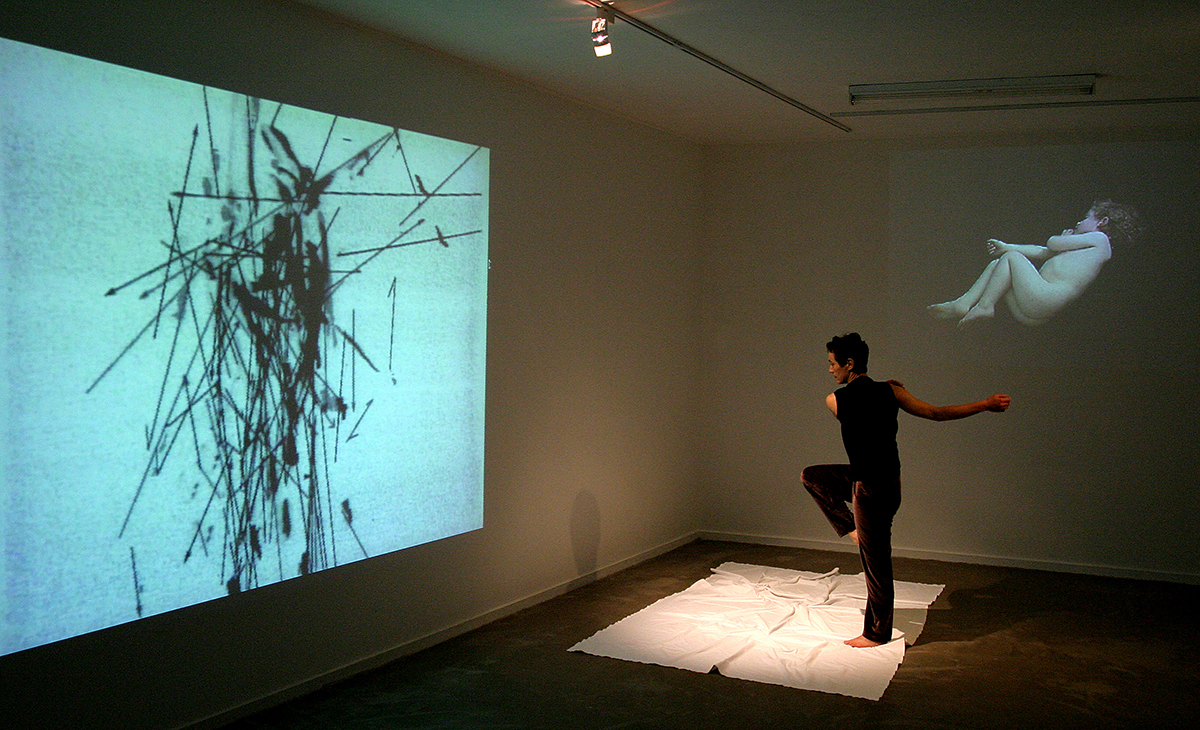

Wendy Morrow, Blue, photo Pling

Threshold 6 (futurism, and fear):

Finally, a piece that (quietly, soft-violently) talks to some of the greatest vulnerabilities in our time. In the hall of the Canberra Contemporary Arts Space, Manuka, 2004: Wendy Morrow and Leigh Hobba recreate Blue, a piece that premiered near the first anniversary of 9/11.

On screen one: a still-frame of a naked toddler with curly hair (Hobba’s son), lying asleep on his side. His hair is a halo almost larger than the rest of him. Slowly, we perceive his small wrist flicker, breath fluttering his bones.

On screen two: a streaming jet, slowed to quarter-time and travelling left to right, disappearing before reaching the edge of the screen. Repeated: travelling; a quiet implosion. The tension this creates — the long journey, the disappearance before impact renders the image a rehearsal for a fate we now know (post 9/11), and of what we then, in this piece’s first showing, anticipated as the about-to-become, the always-capable-of-happening.

We are always already capable of this: violent, violating of the inviolable. Morrow’s body knows all this; her breath holds against it (even in its release): knowing, storing and re-creating the fears and the horrors, the memories and the capabilities of attack.

Her dance represents the movements of a mother in history, mutely rehearsing a defence. It evolves from somewhere beneath the brickwork of the body’s structure — softly, fiercely, yet also, we suspect, is capable of knocking down a mountain.

A pixelated image depicts a line of national flags waving in a night sky. It is a horrible sight. So self-certain. To paraphrase TS Eliot, post-World War 1, so “unreal.”

Morrow’s partnership with Leigh Hobba has produced a subtle, complex, startling piece, full of the yearning for protection and sanctity that any parent knows, and that anyone in the West post-9/11 world has come to understand, was always fragile.

Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa

In the end of all these performances, is my beginning…

–

Top image credit: Trevor Patrick, Wendy Morrow, Sleep, photo courtesy the artists